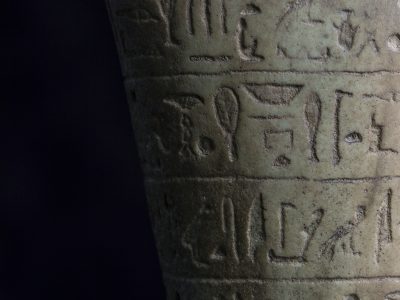

Katie Cuddon, Behind Mother’s Eyes, 2020. Painted ceramic. Photo credit: John McKenzie

The wise baby is a dream image, a condensed and striking representation of the radical fragmentation of the ego. Ferenczi takes dreams seriously, and treats them as the starting point for a novel understanding of the psyche, one that is different from Freud’s.

In his text ‘On the Analytic Construction of Mental Mechanism’, Ferenczi talks about an ex-corporation of the ego that he calls ‘getting beside oneself’. This psychic act requires tremendous psychic energy. As he writes:

Another process requiring topical representation is characterized in the phrase ‘to get beside oneself’. The ego leaves the body, partly or wholly, usually through the head, and observes from outside, usually from above, the subsequent fate of the body, especially its suffering. (Images somewhat like this: bursting out through the head and observing the dead, impotently frustrated body, from the ceiling of the room; less frequently: carrying one’s own head under one’s arm with a connecting thread like the umbilical cord between the expelled ego components and the body.) (p. 222)

Many clinicians working with traumatised patients have noted their accounts of the peculiar moment of exiting the body, of observing oneself from the ceiling, as if the self were an other. This ‘othering of the self’ produces an important dissociation, a sense of exteriority from their own experience. This psychic position of exteriority to the self is available to the subject in subsequent situations that mimic the scene of the trauma. The psychic fragment ‘observing from the ceiling’ marks what I call a ‘pre-Orpha function’. The wise baby is a construct that sits between the state of ‘getting beside oneself’ and Orpha, Ferenczi’s curious psychic agency, which he adds to the Freudian id, ego and superego. Orpha functions as a ‘guardian angel’ – a true, stable and fully shaped dissociation, capable of watching over the abused child, abandoned by all external helpers and subjected to the overwhelming force of the aggressor.

The psychic imagery that accompanies the formation of this psychic position is very striking. The subject does not only ‘find’ herself looking from the outside to their own suffering, but often has a sense of a physical journey to the new ex-corporated state. The movement can be that of leaving the body through the head. Another possible movement can be an image of ‘losing one’s head’ and carrying it under one’s arm. What is crucial here is the representation of the dissociation of faculties. Seeing and thinking (standing for objective perception) are relocated elsewhere, while the rest of the body is left in agony on the ground.

This kind of radical fragmentation can also be made sense of in terms of psychic times. In the scene of trauma, the child can go through an instantaneous maturation, and develop the emotions of an adult. This premature coming of age is often accompanied by being able to perform roles more easily associated with motherhood or fatherhood than with childhood. The playful, spontaneous, gradual appropriation of the world stops, while the traumatised child migrates to a place of ‘carer’ for the narcissistically compromised adults around him, for other children, or even for parts of the self. Another facet of this precocity refers to sexual roles. It is worth noting that it is a fragment of the psyche that goes through what Ferenczi ‘traumatic progression’ or ‘precocious maturity’, and not the entire personality. There is a traumatic bifurcation that happens, which produces a markedly paternal/maternal fragment, and other fragments that are still ‘childfull’, in their needing the presence of the register of tenderness, of gentle care and gradual learning, in order to mature.

Traumatic progression extends to the sphere of the intellect: the traumatised child will be capable of surprisingly wise utterings, sometimes to the delight of the adults around him, who will gratify and encourage faculties that are in fact results of traumatic dissociation. As Ferenczi poetically puts it in his paper, ‘Confusion of Tongues between Adults and the Child’: ‘It is natural to compare this with the precocious maturity of the fruit that was injured by a bird or insect’ (p. 165). Ultimately, Ferenczi regards the intellect as born out of suffering.

In a dream state, this ‘cold’ ex-corporated psychic position characterised by prematurity is represented as the wise baby. It is a tragic baby, a child-interrupted, a child who has seen too much, who knows too much. So how does the analyst encounter the wise baby in the consulting room? Dream images are key here. The wise baby can take many forms. One of my patients once brought a dream where a seven-year old girl who was teaching everyone how to swim, so that they wouldn’t drown while crossing the ocean. In the dream, the girl appeared too clever and articulate for her own age. This dream image helped us in the analytic process, it brought about the work of getting in touch with a profoundly dissociated and omnipotent state, a result of traumatic splitting. Just like Ferenczi’s clever baby, the swimming girl of my patient’s dream proved to be a great helper. I have collected many wise baby images from my patient’s dreams. The appear often, they take striking forms, and they are bound up with possibilities of making links between radically severed parts of the psyche.

References:

Ferenczi, S., ‘The Dream of the “Clever Baby”’ [1923], in: S. Ferenczi, Further Contributions to the Theory and Technique of Psycho-Analysis, comp. by J. Rickman, transl. by J. I. Suttie. London: Karnac, 1994, pp. 349–350.

Ferenczi, S., ‘On the Analytic Construction of Mental Mechanism’ [1930], in: S. Ferenczi, Final Contributions to the Problems and Methods of Psycho-Analysis, ed. by M. Bálint, transl. by E. Mosbacher. London: Karnac, 1994, p. 222.

Ferenczi, S., ‘Confusion of Tongues between Adults and the Child’ [1933], in: S. Ferenczi, Final Contributions to the Problems and Methods of Psycho-Analysis, ed. by M. Bálint, transl. by E. Mosbacher. London: Karnac, 1994, pp. 156–167.

Join the conversation!

You can submit your reflections using the form below.

We welcome reflections on:

- Ferenczi’s text

- Any of our featured responses.

Selected commentaries will be published on the Ferenczi Hub pages.