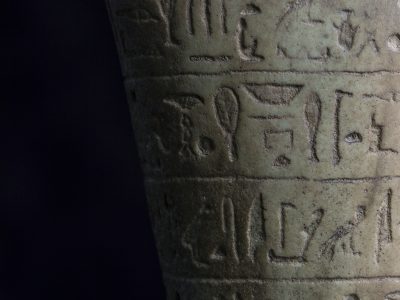

Katie Cuddon, Mother and Baby, 2020

Painted ceramic and webbing, blanket, chair

Photo credit: John McKenzie

1.

I am dreaming. I dream that Ferenczi comes to my office to talk to me. I already know everything he wants to tell me, and I tell him that yes, I will take him into analysis. But before we begin, he will have to choose (finally!) to separate from Freud, abandon IPA, take himself and his findings to safety. Because at sixty, it is too early to die. I, a psychiatrist, never prescribe drugs to my patients; but to him I prescribe massive doses of vitamin B12, to help him overcome his “blood-crisis,” to form “new red corpuscles.” In real life, Ferenczi’s early death, as I read and re-read it in books, always caused me grief and anger. Curiously in the dream I, his distant epigone, became his “wise baby.”

2.

The wise baby condition runs through, as André Haynal (2004) has well shown, Ferenczi’s entire work and life.

Beginning with the first formulation in that dream described in 1923, in which Ferenczi speaks of an infant who expresses himself like adults and teaches them, to the final formulation in 1932, when, in “Confusion of Tongues between Adults and the Child” he states: “[t]he fear of the uninhibited, almost mad adult changes the child, so to speak, into a psychiatrist and, in order to become one and to defend himself against dangers coming from people without self-control, he must know how to identify himself completely with them” (p. 165). The theme of the wise baby recurs throughout the unfolding in the author’s work, focused especially on the theme of countertransference.

To understand this, one must start with Freud’s reservations about this emotional condition of the analyst, and his considering it an inconvenience to be kept in check, if not eliminated.

What does this opposition between Freud and Ferenczi conceal, well before its scientific value, in terms of mere relational activity?

If the wise baby is the “psychiatrist” of his parents, Ferenczi, as such, is driven to focus on the concept of countertransference not only on the basis of his own clinical experiences, but by embodying it in his relationship with Freud.

How to get out of a condition of traumatic dependence on a parent felt to be authoritarian, if not to seek, first, a condition of equality, albeit amidst a thousand ambivalences? Offering one’s severed penis on a platter, is not exactly a good way to seek a relationship of equality, yet, nevertheless, struggling against himself, Ferenczi first seeks a condition of “total and mutual transparency” based on a consensual agreement, and then goes on to offer himself, without getting an answer, as “his own analyst’s analyst.”

What is the meaning of Ferenczi’s venturing into mutual analysis, if not only an attempt to untie a knot left unresolved in his own analysis with Freud, but also to show Freud a way, that of acknowledging the analyst’s conflicts?

And did not Ferenczi’s own death spring from the overwhelming impact of reading, at the master’s home, “Confusion of Tongues” and its emphasis on the need for the analyst to acknowledge in front of the patient his own errors?

Carlo Bonomi (1999, p. 511) writes that underlying this was Ferenczi’s desire that Freud could acknowledge and honestly admit his own “errors” of judgment committed in Ferenczi’s brief and fragmentary analysis; this, while the report read in Wiesbaden dwelt at length on the theme of the analyst’s need to acknowledge his own errors, thus renouncing professional hypocrisy.

Was not Ferenczi’s whole affair a prolonged and desperate attempt to awaken his parents from the sleep of arrogance?

References

Bonomi, C. (1999), Flight into Sanity: Jones’s Allegation of Ferenczi’s Mental Deterioration Reconsidered. International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, 80:507-42.

Ferenczi, S. (1923), The dream of the “clever baby”, in Further Contributions to Theory and Technique of psycho-analysis (p. 349). London: Karnac Classics, reprinted 2002.

Ferenczi, S. (1933), Confusion of Tongues between Adults and the Child, in Final Contributions to the Problems and Methods of Psycho-Analysis (pp. 156-167). London: Karnac Classics, reprinted 2002.

Haynal, A. (2004), La rivoluzione clinica del “wise baby“. In: Borgogno F. (ed.), Ferenczi Oggi (pp. 29-37). Torino: Bollati Boringhieri.

Join the conversation!

You can submit your reflections using the form below.

We welcome reflections on:

- Ferenczi’s text

- Any of our featured responses.

Selected commentaries will be published on the Ferenczi Hub pages.

G. Guasto, MD is a psychiatrist, AFT of Società di Psicoanalisi e Psicoterapia ‘Sándor Ferenczi, Italy.