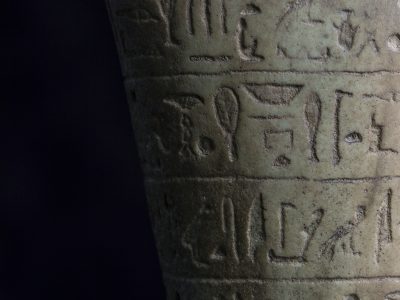

Katie Cuddon, Park Eyes, 2023

Ceramic, paper pulp, plaster, iron powder, human hair

Photo credit: Rob Harris

In a footnote to his 1923 note Ferenczi added: “I do not believe that this communication has in any way exhausted the interpretation of this type of dream, and intends only to turn the attention of the psycho-analyst to it. (A recent observation of the same kind showed me that such dreams illustrate the actual knowledge of the child on sexuality.)” Like those dreams which are revisited over and over again within an analysis, taking on further meaning from each new vantage point, the dream of the wise baby recurred several times in Ferenczi’s development of his ideas on the impact of trauma. Beneath it lies a view of the infant as, initially, an “uncorrupted child”, intuitive, tender, and clear-sighted. Experience threatens the loss of this innocence – as Proust recognised, we are only aware of it once it’s lost – but, for Ferenczi, clairvoyance is, at its purest, a regression to this infantile state.

In Ferenczi’s deepening understanding of the traumatic “confusion of tongues” his “wise baby” plays an important part in the effort to hold onto the shattered experience of being loved. The traumatised child splits his ego, hallucinating lost love in a split-off part of the ego, but also introjecting and identifying with the aggressor. Such a defence was for Ferenczi “flight in a progressive sense” (1995, p. 203): the child matures precociously, becoming clairvoyant to monitor and assess its environment in the service of survival. Reacting with “a kind of mimicry” children in this position “subordinate themselves like automata to the will of the aggressor, to divine each one of his desires and to gratify these, completely oblivious of themselves they identify themselves with the aggressor” (1933, p. 162-163). Their splitting involves an attempt at self-care. One part of the child is innocent but at the same time suffering, the other looks on, attempting to provide for itself a version of the caretaking function that the environment failed to provide, even though the looking on is without emotion.

References

Ferenczi, S. (1933). Confusion of tongues between the adults and the child. The language of tenderness and of passion. In Final Contributions to the Problems and Methods of Psycho-Analysis, ed. Michael Balint. Hogarth Press, London, 1955, pp. 156–167.

Ferenczi, S. (1995). The Clinical Diary of Sándor Ferenczi, ed. Judith Dupont, trans. M. Balint and N.Z. Jackson. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Join the conversation!

You can submit your reflections using the form below.

We welcome reflections on:

- Ferenczi’s text

- Any of our featured responses.

Selected commentaries will be published on the Ferenczi Hub pages.

Ken Robinson is a psychoanalyst in private practice in Newcastle upon Tyne, a member of the British Psychoanalytical Society, Honorary Member of the Polish Society of Psychoanalytical Psychotherapy, and Visiting Professor of Psychoanalysis at the Northumbria University. As former Honorary Archivist of the Institute of Psychoanalysis he played a part accepting the Michael Balint papers into the Institute’s Archives. He is particularly interested in the nature of therapeutic action.