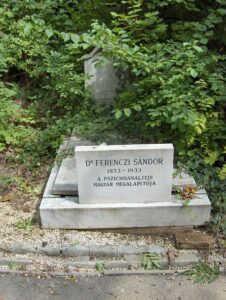

Ferenczi died of pernicious anemia on 22 May 1933, aged 59.

Sándor Ferenczi’s grave at the Jewish Cemetry at Érdi út, Budapest. Image credit: The Androom Archives

The final years of his life were marked by growing disagreements with mainstream psychoanalysis.

Initially met with Freud’s approval, Ferenczi’s increasingly bold clinical experiments and his ideas about trauma came to be seen as deviations.

By the time of his death, enormous tensions had grown between him and the psychoanalytic community, including with Sigmund Freud.

A missed encounter?

Ferenczi never completely broke with Freud, nor did he create his own distinct school of therapy.

Some have suggested that this is because he never fully overcame his need for Freud’s approval, while others have argued that a ‘Ferenczian school’ would go against the spirit of his work.

In psychoanalyst André Haynal’s words:

“The idea of founding a school and encouraging people to act in the way that he, Ferenczi, thought correct was abhorrent to him.”

After his death, efforts were made to marginalise Ferenczi’s contributions. As a result, it took many decades for the psychoanalytic community to recognise the breadth of his contributions and how they shaped the profession.

Even after his death, Ferenczi had a profound influence on the psychoanalytic movement.

Direct paths of his influence can be clearly seen in the work of his analysands and students, such as:

- Melanie Klein (the founder of the object relations tradition)

- Clara Thompson (a central figure in the interpersonal tradition)

- Michael Balint (a major figure in the British independent tradition)

The works of other prominent psychoanalysts such as Anna Freud, Donald Winnicott, John Bowlby and even Jacques Lacan bear the unmistakeable stamp of Ferenczi’s thinking.

More recently, prominent figures in the relational tradition of psychoanalysis such as Stephen Mitchell, Jessica Benjamin and Adrienne Harris have explicitly acknowledged their debt to Ferenczi, and his work continues to influence contemporary psychoanalytic thought.

Ferenczian lessons

Ferenczi broke new ground in his explorations of technique, trauma and the importance he ascribed to the countertransference.

He challenged the classical idea of a neutral, impassive analyst, insisting on psychoanalysis as first and foremost an emotional experience rather than an intellectual process.

Perhaps one of Ferenczi’s lasting contributions was to show that one does not have to be a Freudian to practice psychoanalysis. Ferenczi’s work went far beyond the confines of the Freudian orthodoxy, yet the path he trod was unmistakably psychoanalytic.

Discover more:

Previous chapter

Sándor Ferenczi as a Psychoanalytic Pioneer

Ferenczi quickly gained a reputation as a gifted clinician and theorist.

Enjoying this content?

Please support us!

We rely on the support of our visitors, our friends and our patrons to continue our work.