TRIGGER WARNING: This content contains discussions of childhood sexual abuse. Prioritise your own wellbeing and seek appropriate support if needed when engaging with this sensitive topic.

Ferenczi quickly gained a reputation as a gifted clinician and theorist.

His earliest psychoanalytic publications supported and extended Freud’s basic theoretical ideas, but they also marked significant advances in psychoanalytic thought.

Notable early papers include:

‘Psychoanalysis and Education’ (1908)

One of the first psychoanalytic works to engage with questions of childrearing and education, Ferenczi’s paper draws on psychoanalysis to describe the harmful effects of disciplinarian educational practices, and argues for a more humane alternative.

‘Introjection and Transference’ (1909)

Described by Freud as Ferenczi’s ‘master stroke’, this paper is a landmark contribution to Freudian understandings of the ego, the mother-child relationship and the analytic transference. Today it is regarded as one of the foundational texts for the Object Relations tradition of psychoanalysis.

‘Stages in the Development of the Sense of Reality’ (1913)

Based on Freud’s distinction between the pleasure principle and the reality principle, this paper provides a rich elaboration of how a feeling of omnipotence in infancy is gradually transformed into a sense of reality. It is now considered a key contribution to what would later become the tradition of Ego Psychology.

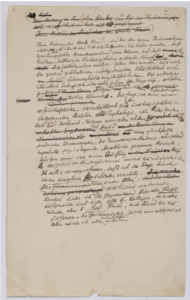

A page from Sándor Ferenczi’s 1932 clinical diary, which documents many of his technical experiments and theoretical developments.

Technical innovations

By the 1910s, most psychoanalysts followed the conventional technique of collecting the patient’s associations and interpreting them back to the patient. However, it was becoming increasingly clear that treatments along these lines were prone to stagnation.

Ferenczi found the effectiveness of the standard technique was especially limited in the complex cases he was taking on, particularly in patients whose symptoms seemed more rooted in trauma than in Oedipal conflicts.

Starting in 1918, he embarked on a series of experiments in technique. Notable innovations include:

Active Technique

In this technical innovation the analyst actively employs suggestions and prohibitions in order to increase internal tensions and thereby provoke enactments of the unconscious, which could then be brought into the work.

Ferenczi argued that active technique should be employed only as a last resort, where the work was stagnating, and that its aim was simply to enable the patient to free associate more effectively.

He soon discovered that his active technique gave rise to problems in the treatment, leading him to abandon it in 1926.

Elasticity

If ‘active technique’ aimed to bring out unconscious material through an increase in inner tension, ‘elasticity’ emphasised the importance of finding the best conditions for a productive analytic dialogue: not too much tension and not too little.

Ferenczi credited one of his patients with coining the term ‘elasticity’. He opposed idea of a detached, authoritative analyst, and instead advocated for one who “like an elastic band must yield to the patient’s pull, but without ceasing to pull in his own direction.”

The technique of elasticity also reveals Ferenczi’s evolving understanding of the countertransference (the analyst’s feelings towards the patient). Unlike classical psychoanalysis, which tended to view the countertransference as an obstacle to be overcome, Ferenczi came to regard it not only as unavoidable but as integral for the analytic work, and increasingly saw value in analysts being emotionally open with their patients.

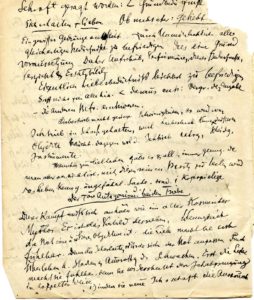

Portrait of Elizabeth Severn, a patient of Ferenczi’s, with whom he experimented with mutual analysis.

Mutual Analysis

In 1932, Ferenczi engaged in a mutual analysis with one of his patients, Elizabeth Severn. He wrote about this in his Clinical Diary, where Severn appears as patient “R.N.” During this mutual analysis, faced with great difficulties in the analytic process, the patient and analyst took turns to analyse one-another.

Ferenczi did not believe that mutual analysis was a new form of analytic practice, but his work with Severn became a laboratory for developing important ideas on ‘mutuality’ in analysis and also on the ‘hypocrisy’ of the analyst.

Mutual analysis is based on the idea that when an analyst struggles to respond in a way that the patient can make use of, they can still create the conditions for the patient to express their perceptions of what the analyst has a problem with in the analytic relationship.

Breaking new ground

Ferenczi’s technical experiments were sometimes radical and not always successful, but they are still regarded as breakthroughs in technique that fundamentally transformed how the analytic situation could be understood.

The figure of the neutral, dispassionate analyst who dispenses interpretations was thrown radically into question. Instead, a vision emerged for a responsive and mutually engaged therapeutic relationship. Ferenczi consistently emphasised the patient’s role as an equal partner who could contribute actively in the healing process.

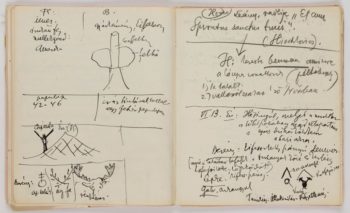

Typescript of a page from a collection of notes written by Sándor Ferenczi between 1930 and 1932. The title of this page reads ‘Trauma and Anxiety’.

A new approach to trauma

Ferenczi’s writings reveal an intense preoccupation with the question of trauma and the treatment of patients who were suffering its effects.

Through his extensive work with patients who had experienced childhood sexual abuse, Ferenczi described the “confusion of tongues” that occurs when a child’s need for tenderness is responded to with adult sexual passion.

Ferenczi observed that such abuse pushes children into a frightening world which can only be survived through extreme defences such as dissociation and splitting of the personality. Consequently, the child often ends up being caught up in an identification with the abuser, and that the abuser’s subsequent silence and unconscious guilt further compound the traumatic experience.

Ferenczi’s technical innovations were largely developed in response to such cases, which he believed conventional psychoanalysis was ill-equipped to treat.

Ferenczi’s trauma theory is an important revision to the Freudian one, and offers a different understanding of the human psyche. His theory does not presume to ‘make sense’ of sexual abuse, but instead offers a rich vocabulary for looking at the many processes of fragmentation that are related to trauma.

Previous chapter

Sándor Ferenczi and the Psychoanalytic Movement

Ferenczi played a major role in the psychoanalytic movement.