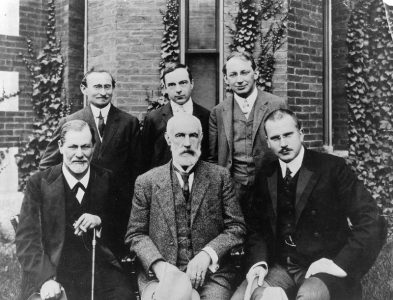

Sigmund Freud and his colleagues with Stanley Hall at Clark University, USA, in 1909. Standing (L to R): A. A. Brill, Ernest Jones, Sándor Ferenczi. Seated: Sigmund Freud, G. Stanley Hall, Carl Jung.

Sándor Ferenczi first met Sigmund Freud on 2 February 1908.

The meeting marked the start of a close friendship and productive collaboration.

Ferenczi made a strong impression on Freud, who immediately invited him not only to present a paper at the First Psychoanalytical Congress in Salzburg that April, but also to join Freud on his family holiday in Berchtesgaden in the summer.

The following year, Ferenczi travelled with Freud, along with Ernest Jones and Carl Jung, to the USA, where Freud had been invited to lecture on psychoanalysis.

Ferenczi and Freud formed an intimate but occasionally strained friendship.

It brought out an authoritarian streak in Freud, and in Ferenczi a longing for emotional closeness.

Ferenczi later reflected that he was seeking in Freud a loving father figure (his own father had died in 1888, when he was 15).

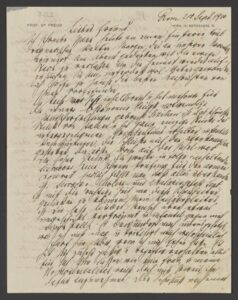

First page of a letter from Sigmund Freud to Carl Jung during his holiday to Italy with Ferenczi, 24 September 1910. Image credit: Library of Congress.

In 1910, the pair travelled to Sicily together. Freud wrote to Carl Jung:

“My travelling companion is a dear fellow, but dreamy in a disturbing kind of way, and his attitude towards me is infantile. He never stops admiring me, which I don’t like, and is probably sharply critical of me in his unconscious when I am taking it easy. He has been too passive and receptive, letting everything be done for him like a woman, and I really haven’t got enough homosexuality in me to accept him as one.”

Here is Ferenczi’s own account of the incident, written much later in a letter to Georg Groddeck:

“On our very first working evening together in Palermo, [he] started to dictate something, I jumped up in a sudden rebellious outburst, exclaiming that this was no working together, dictating to me. ‘So this is what you are like?’ he said, taken aback. ‘You obviously want to do the whole thing yourself.’ That said, he now spent every evening working on his own, I was left out in the cold – bitter feelings constricted my throat.

(Of course, I now know what this ‘working alone in the evenings’ and this ‘constriction of the throat’ signifies: I wanted, of course, to be loved by Freud).

But rather than damaging their friendship, this ‘Palermo incident’ seems to have deepened it. The pair spent many summers together and maintained an ongoing exchange of letters.

The Freud-Ferenczi correspondence (almost 1,250 letters in total) reveals their intimate friendship and functioned as a space for intellectual collaboration. Many of both men’s theoretical ideas were forged in this exchange.

Love turmoil

In 1911, a distraught Ferenczi turned to Freud for advice over a delicate matter.

Since 1904, he had been in a relationship with Gisela Pálos, a married woman some eight years his senior. But in 1911 he became attracted to her daughter, Elma. This complex set of relationships is difficult to pin down and has been analysed in detail by authors such as Emanuel Berman.

Ferenczi wrote candidly to Freud about his emotional turmoil. Freud seems to have been a major influence in Ferenczi’s eventual decision to marry Gisela. Ferenczi would remain torn between a need for Freud’s approval and a need for independence for much of his career.

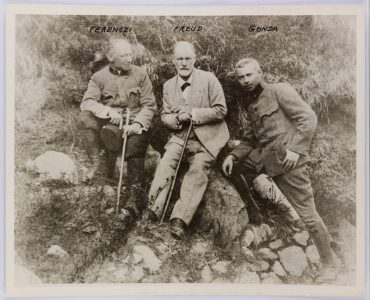

Sándor Ferenczi (left) with Sigmund Freud (middle) and Victor Gonda (right) in 1917, the year after the end of his analysis with Freud.

A brief analysis

Ferenczi was one of the first psychoanalysts to undergo personal analysis as part of his analytic formation.

He was in analysis with Sigmund Freud for three weeks in October 1914, and for another three weeks (with two sessions daily) in June 1916.

Although it didn’t impact their friendship, the analysis became a point of contention between the two men. Freud considered the analysis complete, but Ferenczi later reproached him for failing to sufficiently analyse the negative transference (the hostile feelings from childhood that the patient re-experiences in relation to the analyst during the treatment).

However, it was not until 1927, just six years before Ferenczi’s death, that the first signs of Ferenczi’s gradual withdrawal from Freud appeared.

Discover more:

Next chapter

Sándor Ferenczi and the Psychoanalytic Movement

Ferenczi played a major role in the psychoanalytic movement.