‘A Curator in his own Museum’

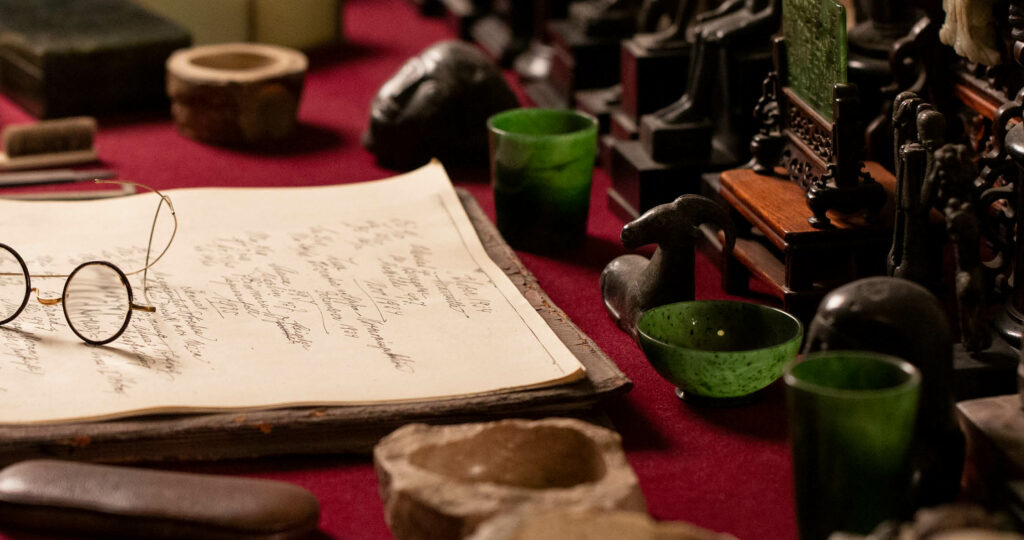

The act of curating is bound up with the very beginnings of psychoanalysis. From the time when Freud began to practice, we know that he started to surround himself with antiquities. We also know that these antiquities populated his working space in 19 Berggasse, not his private apartment. This remained the case when he was able to ‘greet the return of the gods’ in his new home at 20 Maresfield Gardens, now the Freud Museum London, after months of concern that they would not be allowed to follow him out of Nazi occupied Vienna. The poet H.D. remarked how Freud was ‘like a curator in his own museum surrounded by his priceless collection of Greek, Roman and Egyptian treasures’. Freud was not just a collector then, but also a curator. When he arrived as a refugee in London, he relied upon the remarkable memory of his housekeeper Paula Fichtl to ‘position’ his collection as it had been in Vienna, but in this change over, he also made manifestly ‘curatorial’ interventions.

It’s tempting to wonder why, in Maresfield Gardens, the print of Charcot teaching at the Salpêtrière ousted the painting of Abu-Simbel from its position over the couch, the very locus of the psychoanalytic cure. Could this be interpreted as a return to the theatrical ‘primal scene’ of psychoanalysis, at the expense of Freud’s later turn to archaeology? What do we make of the fact that in Vienna, the cast-relief of Gradiva was positioned on the wall above the couch, walking towards the reclining analysand, whereas in London it is positioned by the door to the study as if about to walk out of the room? Could we see this as an uncanny representation of the approach of death; with the early symbol of psychoanalytic desire exiting, stage left?

The very subject of psychoanalysis temps our speculations around such (re)positionings; Freud’s, and by association our, relationships to the objects in his collection are clearly overdetermined. The vanishing point connecting our desire for meaning and the discovery of objective fact seems to recede the closer we get to it.

‘Homely’ Space

Freud’s study is an abundant space, crammed full of objects that are both visible and hidden at the same time. Individual objects get lost in the manifold; an Ancient Greek water jug; a Mesopotamian votive offering; an Etruscan wine jug; are carefully locked behind the glass doors of a cabinet, and tucked around the corner of the room, inaccessible to the observers’ gaze. This is a ‘homely’ space, full of clutter. The objects that occupy this space have a stability which is bestowed upon them by their respective positions within their domestic configuration.

In Freud’s Antiquity: Object, Idea, Desire, we have attempted to de-stabilise certain key objects by removing them from this stable domestic scene and juxtaposing them against other objects to which they may not be immediately or obviously related. We know from accounts of his patients that Freud used his objects to ‘illustrate’ his theories. With the ‘Ratman’, Freud pointed to the objects on his desk to show the difference between the unconscious, which was relatively unchangeable, and the conscious, which was subject to the process of wearing away. This exhibition aims not only to use Freud’s objects to illustrate his theories, but also to use his theories to complicate and enrich his objects.

Freudian psychoanalysis can help us to think of objects as having an unconscious and existing on a continuum between their ‘materiality’ and the fantasies and imaginative webs we weave around them. By inference, individual objects can also take on new meaning(s) when they are displayed alongside other objects; an Etruscan wine jug is not just an Etruscan wine jug, particularly when it is displayed next to a print of Ingres’ Oedipus and the Sphinx, which of course, is not just a print of Ingres’ Oedipus and the Sphinx…

‘Archaeological Metaphor’

The notion that Freud deployed the science of archaeology in order to legitimatise his new science of psychoanalysis underpins this exhibition. The ‘archaeological metaphor’ as it’s commonly referred to, appears throughout Freud’s oeuvre, from Studies on Hysteria, first published in 1895, to one of his final works, Constructions in Analysis, published in 1937. Freud choreographed a career-long pas-de-deux between the two disciplines, which goes through a series of variations and transformations. However, the ‘archaeological metaphor’ never reaches the form of analogy proper, there is never a sense of equivalence between the two terms. Perhaps the most famous textual trace of this unresolved relation is situated in the first chapter of Civilisation and its Discontents, in which, having embarked upon an elaborate 2-page description of the ruins of ancient Rome in attempting to illustrate the way in which the past is preserved in the mind, Freud writes,

The notion that Freud deployed the science of archaeology in order to legitimatise his new science of psychoanalysis underpins this exhibition. The ‘archaeological metaphor’ as it’s commonly referred to, appears throughout Freud’s oeuvre, from Studies on Hysteria, first published in 1895, to one of his final works, Constructions in Analysis, published in 1937. Freud choreographed a career-long pas-de-deux between the two disciplines, which goes through a series of variations and transformations. However, the ‘archaeological metaphor’ never reaches the form of analogy proper, there is never a sense of equivalence between the two terms. Perhaps the most famous textual trace of this unresolved relation is situated in the first chapter of Civilisation and its Discontents, in which, having embarked upon an elaborate 2-page description of the ruins of ancient Rome in attempting to illustrate the way in which the past is preserved in the mind, Freud writes,

There is clearly no point in spinning our phantasy any further, for it leads to things that are unimaginable and absurd. If we want to represent historical sequence in spatial terms we can only do it by juxtaposition in space: the same space cannot have two different contents. Our attempt seems to be an idle game. It has only one justification. It shows us how far we are from mastering the characteristics of mental life by representing them in pictorial terms.

An idle game, perhaps, but it’s a game that Freud kept playing till the very end. And it’s a game that Freud’s Antiquity: Object, Idea, Desire also plays. Visitors to the exhibition will be able to dig under the ‘manifest’ layer of the physical exhibition, and discover a new ‘latent’ digital archive, which explores the hidden connections between the objects on display and provides a rich resource for further research. Thinking in analogical terms, we could describe the Freud’s Antiquity exhibition as a ‘symptom’ and the digital archive as a ‘cause’. Following Freud’s suggestion in Little Hans, we encourage visitors to ‘seek a knowledge of the causes’ behind the symptoms. In his final use of the ‘archaeological metaphor’, in Constructions in Analysis, Freud suggests that the work of excavation inevitability leads to the act of construction: just as the archaeologist constructs historical meaning through the manner in which they create a matrix of relations between different objects excavated at the site, so the psychoanalyst constructs meaning by bringing the analysand’s fantasies, memories and dreams into relation with each other. Desire is always at the heart of the psychoanalytic search for meaning, or as Freud wrote, ‘past present and future are strung together, as it were, on the thread of the wish that runs through them’. By creating a new matrix of relations between the objects on display in Freud’s Antiquity: Object, Idea, Desire, we invite the viewer to think about the desires that engender their own relationships with the objects that they choose to surround themselves with… why that vase…?

Freud’s Antiquity: Object, Idea, Desire

25 February 2023 to 16 July 2023

Freud’s Antiquity: Object, Idea, Desire would not have been possible without the generous financial support of Kings College London, UCL, the AHRC and the University of Houston, which has allowed us to purchase new photographic equipment and display cases that help visitors to get closer than ever to some of Freud’s best-loved and most evocative objects. The most important support however was given by Professor Miriam Leonard, Professor Daniel Orrells, and Professor Richard Armstrong, whose scholarship and generosity are the true latent causes behind this endeavour.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Comments

It’s really funny when now there are many people who claim to be respectable archaeologists but don’t even know to determine the truth.

The exhibition “Unstable Objects: On Curating Freud’s Antiquity: Object, Idea, Desire” is indeed a remarkable showcase. It brilliantly captures the intricate relationship between Freud’s collection of antiquities and his pioneering theories. The way the exhibit intertwines ancient artifacts with Freudian concepts is not only insightful but also creatively engaging. It offers a unique perspective on how objects of art influenced Freud’s ideas, enriching our understanding of his work and its enduring impact on psychoanalysis and art history. Kudos to the curators for such a thought-provoking and beautifully presented exhibition!