This is Part 2 of Dr Warren’s writing on Marie Bonaparte. Read Part 1 here.

Marie Bonaparte in the Museum’s Archive

I wondered what else the archives might reveal about Marie Bonaparte. I was curious about two main questions. First, is there more to discover about this remarkable woman, an unlikely feminist theorist in the early 20th century; and second, have scholars of Freud and of psychoanalysis more generally sufficiently catalogued and analyzed her intellectual contributions? A search in the Museum’s catalog revealed over 280 items related to Marie Bonaparte in the archives, most of these letters and photographs. What struck me, however, is that Bonaparte materials are scattered widely across the collections of Sigmund, Martin, Anna, and Lucie Freud, as well as those of Dorothy Burlingham, Mathilde Hollitscher, Josefine Stross, Tini Maresch, and Ida Fairbairn to name the most prominent.

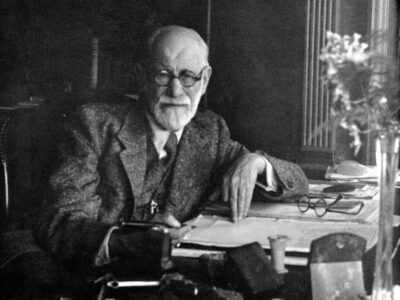

In their generous reflection on Bonaparte, Lisa Appignanesi and John Forrester comment on the significance of “letters” to Bonaparte’s life. Bonaparte was a prolific writer; Freud described her as having “the working capacity of a man.”[1] She wrote volumes of notes, plays, essays, and stories as a child, in “copybooks” which would prove key to her analysis with Freud as well as her own memoir. As a scholar, she produced numerous essays, conference papers, and books in her adult life and was widely acknowledged as an intelligent interlocutor in psychoanalytic circles.

The treasure that the Freud Museum archives reveal, however, is that she also maintained an enduring and diverse personal correspondence with virtually every member of the Freud family. The significance of her exchange with Sigmund Freud is evident throughout Freud scholarship. The letters Freud writes to Bonaparte figure prominently in Ernest Jones’s description of the Professor’s later years, for example. Yet, Marie also showered generous attention on Martha, the Frau Professor, as well as Mathilde Hollitscher, Freud’s eldest daughter. Over 40 letters remain of her exchange with Hollistscher, many of them written during the most difficult years of the war for both women.

Marie Bonaparte and Anna Freud

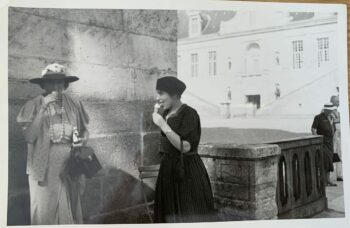

Fig 6. Marie Bonaparte and Anna Freud enjoy ice cream in the shade.

Fig 5. Marie Bonaparte and Anna Freud at a professional congress on psychoanalysis.

Bonaparte also maintained a noteworthy friendship and correspondence with Anna Freud until the Princess’s death in 1962. The two women appear frequently in photographs together, clearly enjoying both professional and leisure time in each other’s company. In one of my favorite photographs, the two relish ice cream cones in the shade.

Anna, of course, wrote loyally to her dearest friend, Dorothy Burlingham, during her travels in the 1950s, and she often mentions “the Princess,” sometimes with concern about her health and stamina, other times to celebrate the brilliance of her conference papers or dinner parties. In 1959, from Lille Bernstorff, Prince George’s Danish palace where a symposium was held, Anna writes that the Princess initially “looks alarmingly tired,” but soon seems “better” and preoccupied with the details of planning a party for 200 guests. Anna later describes the Princess’s paper as “the best by general recognition” and the party “a great success for the Princess.” This caring attention to the Princess’s professional and personal well-being is characteristic of Anna’s letters to Dorothy in this period and illuminates the intimate nature of their relationship.

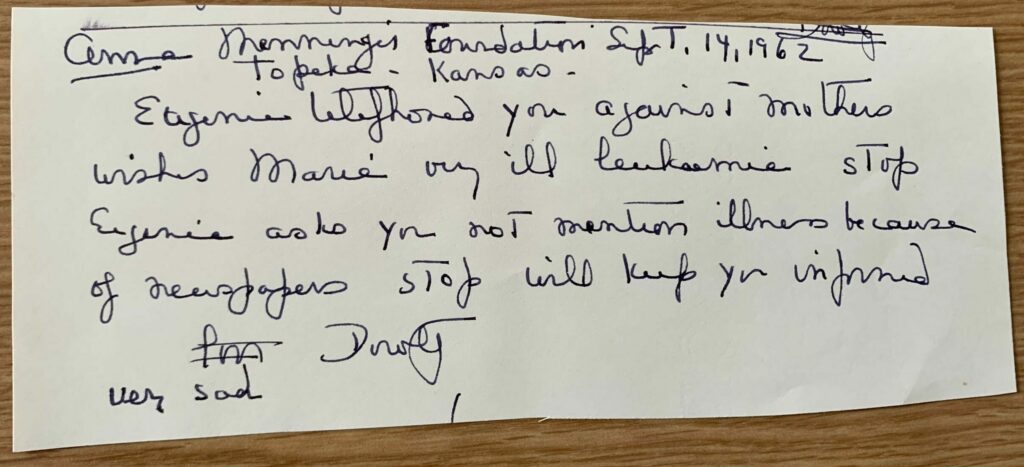

Fig 7. Dorothy Burlingham’s drafted telegram dated September 14, 1962 informing Anna Freud of Marie Bonaparte’s illness.

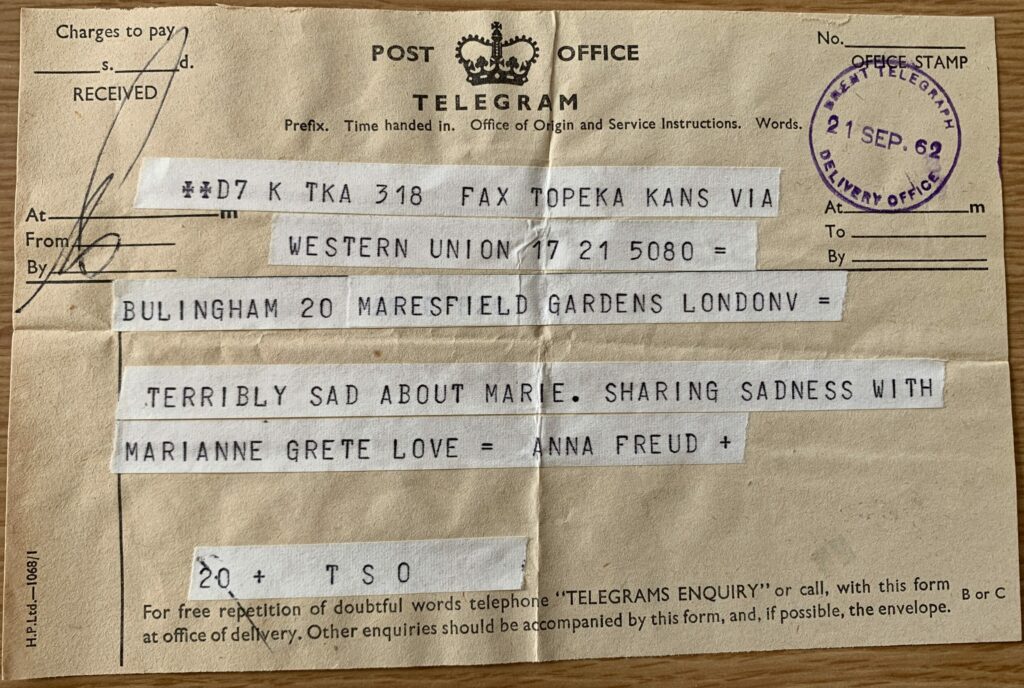

Fig 8. Anna Freud’s telegram response to Burlingham, noting her sadness in response to the news.

In 1962, the Menninger Foundation in Topeka, Kansas welcomed Anna Freud as the Sloan Visiting Professor, and it was during her stay in the US that she received news about the Princess’s ailing health. On a draft of her telegram to Anna, Dorothy writes, “Marie very ill leukemia,” “will keep you informed,” “very sad.”Anna’s response arrives quickly as well, “Terribly sad about Marie.” In a longer letter on the 21st of September, Anna describes her distress about being so far away: “If I were in London I would fly there,” she writes. Anna appears to be bracing herself for a subsequent letter with worse news. “I see her suddenly and wonder if she is dying,” she laments. When news of her passing finally reaches her, Anna begins her letter sadly, “So it did come as I feared with the Princess. I wish I could have gone once more to see her.” Anna also expresses concern for Marie’s daughter, Eugenie whom she would have liked to have been there to support.

These are the emotions and expressions of a close friend mourning the loss of a loved one. The letters dispute whispers in Freud scholarship that suggest Marie was nothing but a duped acolyte or an eccentric dilettante whom Freud conveniently accepted because her stature and wealth benefited him and his plans for psychoanalysis. In Sigmund and Anna’s correspondence, Marie fleshes out as a formidable scholar, a generous friend, and a delightful rebel, fearlessly pursuing her racy interests and protective of those she loved.

Final thoughts

Most scholars of psychoanalysis readily agree on several of Marie Bonaparte’s material and intellectual contributions, and especially her devotion to women’s pleasure. There is also relative consensus about her remarkable ability to preserve Freud’s papers and his legacy. Contemporary scholars have also begun to re-examine her colonial entanglements, racialized understanding of the body, and the potential value of her scientific research on women’s genitalia. However, I would venture that there remains more to uncover about this remarkable figure. My work in the archives has just begun, and as I embark on the translations of her letters, I hope to bring fresh attention to Bonaparte’s life, legacy, and place in the intellectual history of psychoanalysis.

I’m extremely grateful to the generous staff of the Freud Museum and everyone who welcomed my presence in the charming upstairs office where an open door welcomes fresh summer breezes off the garden. Thanks especially to Bryony Davis, curator and archivist, who graciously assisted me with the materials, and to Carol Seigel who encouraged me to explore the archives and write this reflection. Finally, a special thanks as well to Professor Brett Kahr, Honorary Director of Research, who provided keen insight in conversation and throughout his new book, Freud’s Pandemics (London: Karnac Books, 2021) and offered me an early opportunity to discuss the direction of my research.

Notes

[1] Lisa Appignanesi and John Forrester, Freud’s Women (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1992), 346.