First visit to the Freud Museum

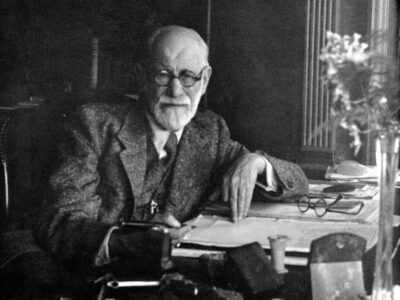

My first visit to the Freud Museum in 2019 was inspired by my travel companion, an American psychotherapist eager to pay tribute to the complex figure at the core of her professional work. As a scholar of film and feminist studies, Freud has also been a consistent reference in my own training, and I readily agreed. We moved through museum that day utterly fascinated by the many dimensions of Freud revealed by his art collection, his crowded desk, and famous couch, of course, but more thoroughly by the sheer number of his personal belongings, which we knew had been miraculously salvaged from his apartment in Vienna and the violent intentions of the Nazis.

We had spent that same morning at the Jewish Museum and the fate of millions of European Jews weighed heavily on our hearts. At the precise moment when so many had been in the process of losing everything, what had allowed Freud to escape not only with his life and his immediate family, but also with what appeared to be every jade stone, beloved book, and ancient statuette in his collection? How had his life remained so intact? The answer to this question would come to me unexpectedly many months later and would eventually lead me to a rich and productive research visit to the Freud Museum archives.

In the wake of the #MeToo movement, I had turned my attention to scholarship on the politics of sexuality, and to the intellectual history of pleasure, and it was there that I first encountered Marie Bonaparte, Princess of Greece and Denmark, and the grandniece of the infamous emperor – a woman Freud called, “my dear Princess.” In sexuality studies, Bonaparte is often sensationalized as a courageous (but misguided) scientific innovator who submitted to experimental surgeries to alter the placement of her clitoris to improve her experience of sexual pleasure. Fascinated by her devotion to pleasure, I sensed there was far more to the story. Indeed, I would come to learn that it was Bonaparte who leveraged her royal connections and notable wealth to help secure the Freud family’s safety in exile in London, including the preservation of his possessions and his legacy.

Princess Bonaparte and Professor Freud

Although their time together lasted only from the mid-1920s until his death in 1939, Princess Bonaparte and Professor Freud developed a deep friendship, abundant with intellectual collaboration and mutual admiration. Martin Freud poignantly refers to Marie Bonaparte as “the dearest friend of father’s later years” and observes that the family’s last weeks in Vienna “would have been quite unbearable” without her presence.[1] One obvious sign of her impact on his life is the fact that Freud’s ashes were laid to rest in an ancient Greek urn that was a gift from Bonaparte.

Princess Marie Bonaparte, who was also the aunt of the late Duke of Edinburgh, discovered psychoanalysis through Freud’s Introductory Letters on Psychoanalysis, which she read at her ailing father’s bedside in her early forties. She was already deeply engaged in scientific research about women’s sexual pleasure and orgasms, a topic she pursued passionately in her personal and professional life. The fiercely independent and scholarly Princess maneuvered her way to Freud’s couch in Vienna in 1925, rather desperate to overcome her anorgasmia and more broadly interested in training as an analyst. At the time, the venerable Professor was besieged by debilitating cancer treatments and reluctant to take on the Princess, but their collaboration proved to be deeply meaningful for both. After he began analysis with her, he wrote to his colleague René Laforgue, who had made the request for treatment on behalf of the Princess, and admitted that he was most grateful and inspired by his work with her.

Bonaparte’s status, wealth, determination, and social credentials made it possible for psychoanalysis, which the French perceived as “the Jewish science,” to take root and eventually thrive in France. Her devotion to Freud and his family undoubtedly helped secure his intellectual and material legacy as well. During their friendship, Bonaparte generously supported Freud’s endeavors in publishing, translated his works, funded psychoanalytic journals and institutes, and delighted in giving gifts to the family, including the Professor’s favorite Chows. One of her most courageous decisions was to purchase Freud’s intimate letters to Wilhelm Fleiss and then to refuse Freud’s request to surrender the letters to him fearing that they would be destroyed. Bonaparte preserved the letters on a miraculous, secret journey during the war from Paris to Vienna to London, at one point waterproofing them for a journey across the Channel, certain that the Nazis would have destroyed them if they had been discovered.

Tracing Princess Bonaparte in the Museum’s public spaces

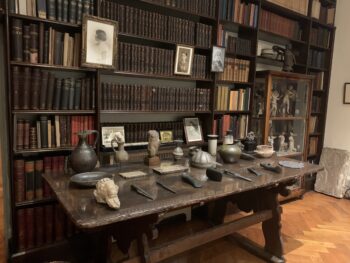

Fig 1. Photographs of Princess Marie Bonaparte and other significant women in Freud’s life grace the bookshelf opposite the famous couch.

The Freud Museum pays tribute to Bonaparte and her friendship with the family in virtually every room in the house. On the first floor in the entryway display case, we find a series of photographs that document the family’s flight from Vienna to London. “Freud Arrives in Paris on His Way to London,” reads the headline over a famous photograph of the Professor in the company of Marie Bonaparte and the US Ambassador to France, William Bullitt, on the 5th of June 1938. The case also displays the certificate of taxes Bonaparte paid to the Nazis, which allowed the Freuds to leave Austria.

In the study, there are two photographs of Bonaparte on the bookshelf opposite the couch where several other photographs are displayed, notably all of women. In one she poses with her cherished Chow outdoors, likely on a picnic. She is characteristically elegant and casual at once, smiling graciously. The other is a more formal portrait of the Princess, signed and dated for her beloved Professor. Although not included here, Bonaparte also took photographs of Freud in his study in Vienna and several extant photographs reflexively document her in crouching to capture him posing there.

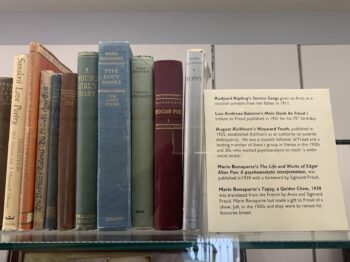

Fig 2. Marie Bonaparte’s major books on the shelf in the Anna Freud room.

Fig 3. Photographs of Marie Bonaparte, including one with Anna, in the Anna Freud room.

Bonaparte comes to life again and more robustly in the Anna Freud room, which includes more photographs of her as well as several of her books, including Female Sexuality (1951), her study of Edgar Allen Poe, and a children’s book about loving animals, Topsy, A Golden Chow, which Freud and his daughter Anna would translate into German, a minor comfort in the tumultuous year before their departure from Vienna. Two more photographs of Bonaparte appear in the display case: another formal portrait of the young Princess, posing with an open book on her lap, and a candid photograph of the mature Marie with Anna, likely at a Psychoanalytic conference, which they often attended together throughout the 1950s. Here, Bonaparte is described as a “writer and psychoanalyst,” as well as given credit for provoking Freud’s famous question about women’s desire, in addition to her role as an essential family friend.

Fig 4. Marie Bonaparte is highlighted in James Roberston’s 1956 footage of the garden party following the unveiling of the commemorative plaque at Maresfield Gardens.

Finally, Bonaparte appears in the moving images throughout the house. In the wonderful, color film footage taken by James Robertson of the unveiling of the commemorative plaque honoring Freud in 1956, Princess Marie is described as a having “played a large part in getting Sigmund Freud to England.” In the Home Movies in the viewing room, Marie Bonaparte is credited for capturing some of the footage, including of the Professor in his Berggasse study. In voice-over, Anna also remarks upon Bonaparte’s loyal friendship with the family, particularly in the footage of the family’s difficult voyage to England.

In all these spaces, open to the public, Bonaparte is a recurring figure in the story of the house, the history of psychoanalysis, and in the lives of the Freud family. Of course, as psychoanalysis teaches us, these visible signs may be simply traces of a deeper and more complex story about the entwined lives of the Princess and the Freud family.

This is the first part of Dr Shilyh Warren’s reflection on Marie Bonaparte.

Notes

[1] Martin Freud, Glory Reflected (London: Angus and Robertson, 1957), 190, 214.