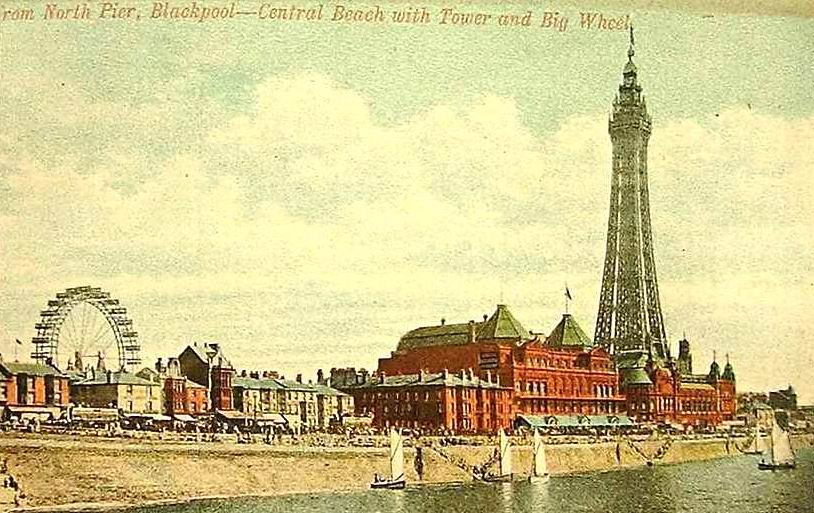

The word ‘reisemalheurs’ is taken from a letter written by Sigmund Freud to his family while on holiday in Blackpool in 1908.

Freud’s postcard home from Blackpool, 1908

It invokes the mishaps and misfortunes attendant on travel, in this case tourism, but is suggestive too of the wider travails and stresses of journeys, both forced and voluntary. Freud travelled widely in his life but often expressed anxiety about and resistance to travelling. The drive to travel and the dread of travel permeate his correspondence and creative thought. The work of the South African, New York based artist, Vivienne Koorland, thematises the pain and dislocation of being away from ‘home’, itself a mythic place, the stuff of dreams and fantasies rather than a secure or comfortable location.

Born in Cape Town in 1957, Koorland herself is of no fixed abode. She left Cape Town as a graduate student in 1978 to attend the Hochschule der Kunste in Berlin, and then went on to study at the Ecole Normale Superieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris. In 1982 she moved to New York which has been her base ever since but her links to Europe have remained strong, with her close family in London, and her connection to Africa is deep. Travel is therefore part of the condition of Koorland’s life. Returning to Cape Town repeatedly over the nearly three decades since her departure, Africa remains a key reference point in her work. So too does Eastern Europe. Koorland’s mother is a Polish born, Jewish holocaust survivor, an orphan sent to the Jewish orphanage in Cape Town after the war. But while registering personal experience, the work is not autobiographical. Indeed travel, transportation, journeying and dislocation is so much part of modern experience that Koorland’s work draws on a wide range of cultural references and sources that thematise displacement.

Wishlist, 2006, Vivienne Koorland

Using images, texts, forms and templates taken from diverse representational practices, Koorland speaks through the voices of historical subjects, both fictitious and actual, in order to salvage the iconic and textual fragments and records of human displacement. In a list of numbered words and phrases, painted onto monumental canvas. Wishlist, Koorland includes the word ‘Reise-malheurs’, the term which gives the show its title. An unattributed quotation, the word appears alongside a list of phrases in which travel is variously invoked: ‘a Siberian dream map’, ‘circle the sacred mountain’, ‘from Cape Town to Katmandu’. On another occasion the word ‘Reisemalheurs’ appears together with ‘Bahnhofsstimmung’ and ‘la melancholie des Paquebots’ (the anxious moodiness of travel) drawn from Flaubert via the writing of Edward Said. Points of reference, spatial as well as cultural, geographic and literary, these pieces of text form a private inventory of experience interspersed with the stories of others.

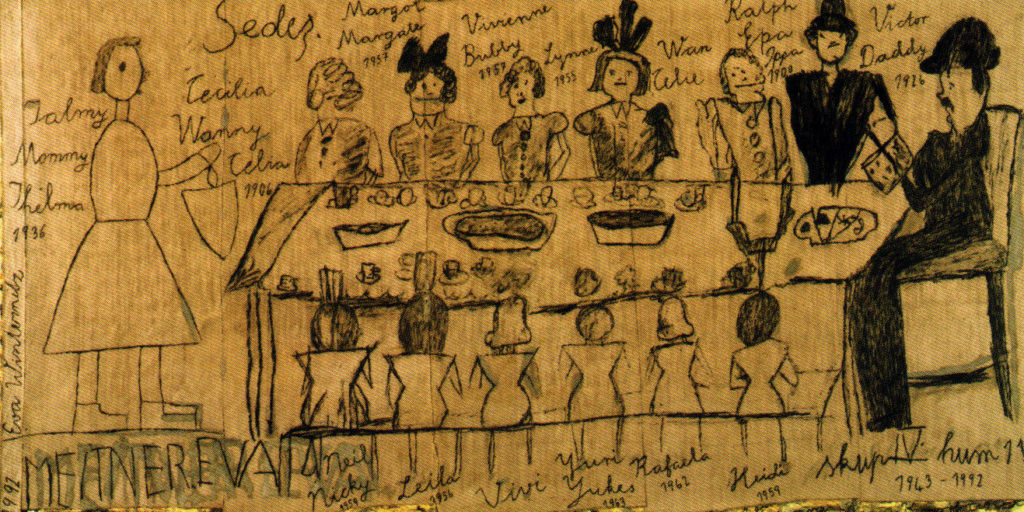

This is the key to Koorland’s aesthetic. Painting for her functions as a palimpsest for received, recycled and reprocessed materials. Using as her ‘source’ children’s drawings from war-torn Europe, poetry written by the Austrian poet Friederike Mayrocker, extracts from the journals of Joseph Roth, lists compiled by Vladimir Nabokov or phrases culled from Sigmund Freud (amongst others), Koorland composes text and image in new conjunctions but always through the voice of ‘others’. Even the script that she uses, the numbers, letters, strokes and lines are drawn from previous paintings, drawings and templates so that she represents the materials of history in forms that make us look at them afresh rather than in inventions culled purely from the imagination. In keeping with the obsession with journeys and displacement , the paraphernalia of travel forms part of the scaffold of Koorland’s visual lexicon: maps, grids and lists often form the basis of her formal structures, but always exceed their instrumental function and operate as metaphors and models of imaginative reconstruction.

This Is The Picture We Saw (Little Hans), Vivienne Koorland

Found drawings also provide important sources for Koorland’s work. This Is The Picture We Saw (Little Hans) involves the transcription and reproduction of a child’s drawing made during World War II. Its caption reads: ‘Bolsheviks are chasing the civilian population away from train cars in which they were deporting the Poles…’ This is a scene of murder as pictured by a historical witness ‘Adam’. The wagons used to transport the people are reproduced by Koorland at the top of the stitched, barely scrubbed in, canvas, but they recur in a number of related works. On one occasion they appear, stranded, amongst the place names and military huts of an imaginary South African Landscape in Cape Town over Hungary, which itself obliterates an earlier upside down painted map of war-torn Europe with its place names still showing through. Places and event converge. Chronologies are inverted and histories are mapped onto one another.

The house is another recurring motif whose source is taken from the drawings of children who, having lost both home and family return in representation to the mythic rectangular safe-house of fantasy. Sometimes suspended in a dark sky enveloped in a constellation of flowers/stars, the house is never rooted or solidly placed. Nowhere is this more poignantly felt than in the melancholic Dream Painting – She Flew Over to Comfort me in which simple box houses are perched precariously on cliff tops, afloat on a stitched burlap ground.

Other sources that Koorland uses include poetry written by the Austrian poet Friederike Mayröcker, extracts from the journals of Joseph Roth, lists compiled by Vladimir Nabokov, Alain Resnais film stills or phrases culled from Sigmund Freud. Musical terms provide evocative reference points in many of her works. Koorland composes text and image in new conjunctions but always through the voices of ‘others’. Even the script that she uses, the numbers, letters, strokes and lines are drawn from previous paintings, drawings and templates so that she represents the materials of history in forms that make us look at them afresh rather than in inventions called purely from the imagination.

The paraphernalia of travel forms part of the scaffold of Koorland’s visual lexicon: maps, grids and lists often form the basis of her formal structures, but always exceed their instrumental function and operate as metaphors and models of imaginative reconstruction. Her maps cannot help you to find your way. Nor do her lists amount to a logical accumulation of information. Her use of borrowed languages and private inventories is poetic rather than practical.

War Drawing Eva Seder I, Vivienne Koorland

Koorland’s use of mapping and listing invokes the practices of daily life. Freud, for example, kept lists and maps to aid his memory and guide him on his travels. To coincide with the exhibition the Freud Museum mounted a display of travel-related materials drawn from its own archive, including maps, photographs, post cards and objets d’art collected by Freud on his many journeys as well as letters and documents from the archives.

Displacement, whether from self, from the womb or from the ideal of integrated subjectivity, is inescapable and all human beings in Freud’s theorization of subjectivity remain exiled from home. It is this wider sense of dislocation, imbricated with the terrible migrations that history necessitates as well as the private displacements of personal journeys that Koorland’s work invokes, in its quiet, detached and highly self-conscious formal languages.

Koorland addresses themes of displacement and dislocation using formal structures such as maps, lists and images borrowed from historical sources and reworked in materially dense paintings.