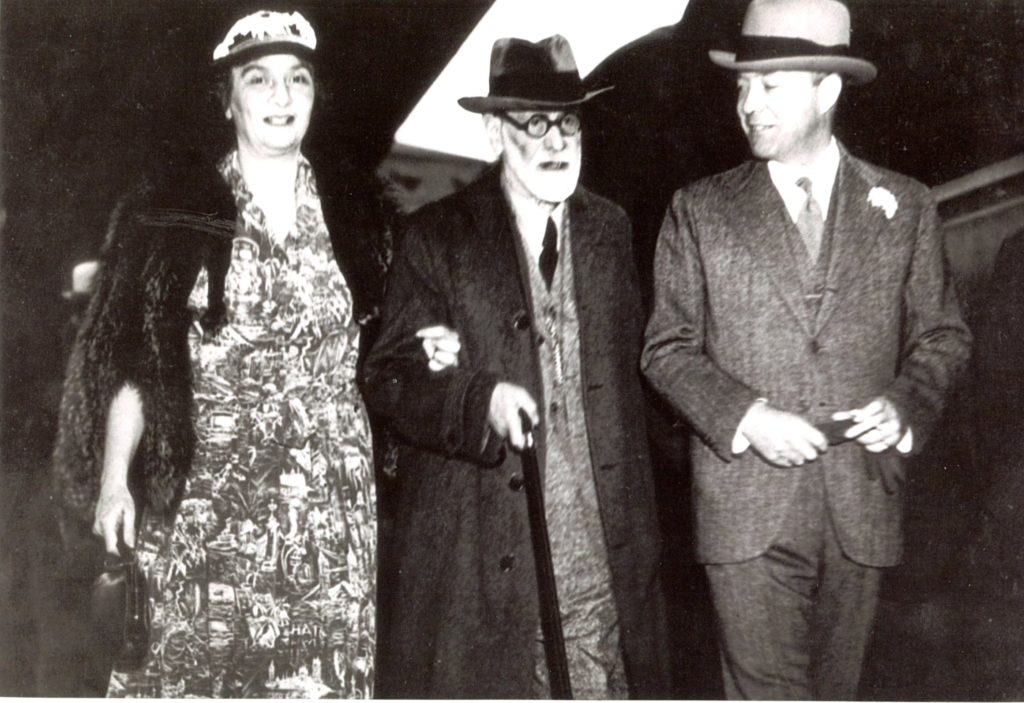

Marie Bonaparte and William Bullitt meet Freud in Paris from his train from Vienna, 1938

This exhibition, first shown in 1996, has been brought back as a counterpoint to Freud’s Wanderlust. The two exhibitions face each other in the same exhibition space, as two contrasting aspects of travel. Wanderlust shows Freud the passionate traveller: Exiles shows him as a refugee and sketches the cultural background and historical forces that determined his fate and that of his family. It covers their history beginning with their economic emigration from Freiberg to Vienna in 1859 and ending with the flight from Nazism to England in 1938.

What was Freud’s “promised land”? As far as nationality was concerned, he was born a “Mosaic” (i.e. Jewish) Austro-Hungarian and he died nominally German but actually a stateless refugee.

In exile he completed a final work, Moses and Monotheism, which has intrigued and baffled readers ever since. In dreams images are displaced and condensed. In that book the protagonist Moses shifts shape like a dream figure – but the dream was world history.

Driven by the Nazis from his home in Vienna at the age of 82, Freud like millions of others became a “displaced person”. He found refuge in England. Did he also find peace in London? In his final home at Maresfield Gardens a film now shows him enjoying a garden party. But appearances are, as always, deceptive. The only recording of his voice ends the film and his last sentence is:

“But the struggle is not yet over…”

This exhibition shows how two pseudo-ideologies, nationalism and antisemitism, affected Freud’s life.

Contemporary documents and objects – a visitors’ notebook, a Nazi tax document, letters and items from his collection of antiquities illustrate his sense of nationality and tell the story of his life-long confrontation with antisemitism, his flight from the Nazis and his final year in London.

Emigration and the Freud Museum

Athena

The exodus of German and Austrian scientists and intellectuals in the 1930s left an indelible mark on Europe and America. Their influence is diffused throughout our culture, yet few visible memorials of these momentous changes remain.

· This exhibition is a focus for that theme. The Freud Museum survives today not only as a monument to one man’s exile but also to the cause of intellectual freedom.

The Freud Museum at 20 Maresfield Gardens became the home of Sigmund Freud and his family when they fled Nazi persecution in 1938. Freud had been a life-long anglophile since his first visit to England at the age of 19. In a letter to H G Wells in July 1939 he confessed that he had nurtured “an intense wish phantasy” of becoming an Englishman. Wells invited Freud to consider becoming British, and enlisted the support of the MP, Oliver Locker-Lampson who proposed a parliamentary bill to confer citizenship on Freud. The bill failed: however in some senses Freud achieved his “phantasy” through his children.

The Freuds were able to bring all their possessions with them to London in 1938, including his remarkable collection of antiquities and his library. These were set up for him here so that his entire working environment was preserved – a fragment of the complex intellectual life of fin de siècle Vienna transported to London.

As early as 1933 Freud’s friends began advising him to emigrate to England. But though the Nazi threat hung over Austria for the next 5 years, he remained in Vienna, in the belief that the Austro-Fascist regime and the Catholic Church together would form a bulwark against Hitler’s Germany. When the “Anschluss” finally came in 13 March 1938, he was left with no alternative but to try to get out of the trap that had closed round him and his family. Two days later Freud’s flat was searched: mass arrests of the Nazis’ political opponents and attacks on Jews began immediately. On 22 March Anna Freud was held for an entire day by the Gestapo for questioning, perhaps the most anxious day of Freud’s life. Luckily the Freuds had powerful political friends. The American ambassador in Paris, William C. Bullitt, saw that the American authorities in Vienna and Berlin should take care that he was not molested: meanwhile Ernest Jones used his political connections to obtains entry visas to England as quickly as possible.

England was the obvious choice for his new home. His most successful son Ernst and his family had already established themselves there since 1933. With the emigration of Jewish analysts from Germany during the 1930s London had now become the European centre for psychoanalysis. And above all Freud had been an anglophile all his life, he spoke the language fluently and admired the culture.

It required a long struggle with the German bureaucracy, and the payment of a huge “refugee tax” in order to obtain exit visas for himself and his entire family entourage, together with a housemaid, a doctor and a dog. Moreover all the belongings he had amassed, his library, archives, furniture and antiquities collection had to be packed and left in storage until they could be cleared for export. “They say that when a fox is trapped by one leg it bites the leg off and limps away on three legs. We will follow its example.. “ Freud wrote to his sister-in-law Minna Bernays (20.5.1938).

It required a long struggle with the German bureaucracy, and the payment of a huge “refugee tax” in order to obtain exit visas for himself and his entire family entourage, together with a housemaid, a doctor and a dog. Moreover all the belongings he had amassed, his library, archives, furniture and antiquities collection had to be packed and left in storage until they could be cleared for export. “They say that when a fox is trapped by one leg it bites the leg off and limps away on three legs. We will follow its example.. “ Freud wrote to his sister-in-law Minna Bernays (20.5.1938).

After nearly three months wait, the Freuds could finally leave on 4th June 1938. As they crossed the French border on 4 June 1938 Freud said simply: “Now we are free.”

Later that year, at his new home in London, in a broadcast for the BBC Freud summarized his experience of emigration in similar simple terms:

“At the age of 82 and as a result of the German invasion, I left my home in Vienna and came to England, where I hope to end my life in freedom”.