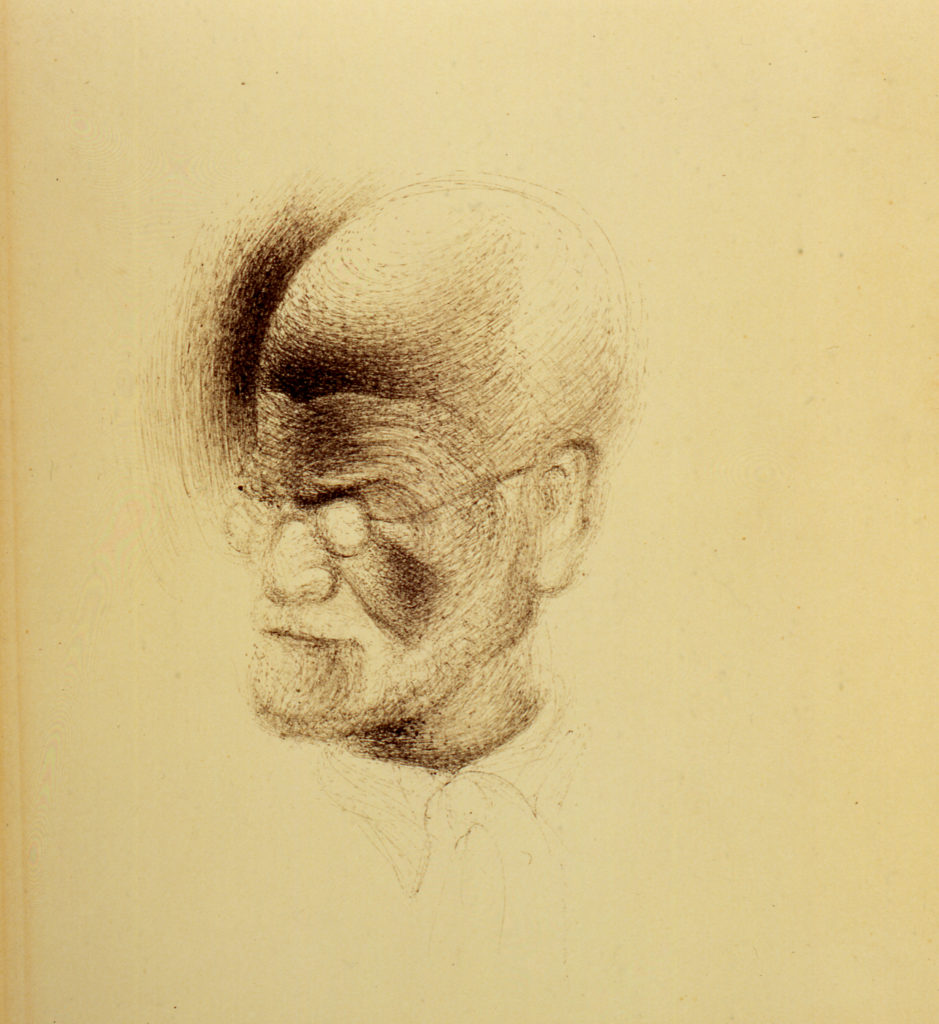

Drawing of Sigmund Freud by Salvador Dali [LDFRD 6388], © Freud Museum London, DACS 2018

We had the rare opportunity to see the three known portrait sketches of Sigmund Freud by Salvador Dalí at the 2018 Freud Museum London exhibition, Freud, Dalí and the Metamorphosis of Narcissus. Each drawing is so distinct and unlike the other two that interesting questions arise about the circumstances of their creation, not least which was done from life.

Freud had been persuaded to see Dalí by their mutual friend the Viennese writer Stefan Zweig. Dalí was, Zweig wrote to Freud, the only genius among contemporary painters ‘and the most faithful, the most grateful of the disciples you have among the artists. This true genius has longed to meet you for many years…’ Zweig, Dalí and Dalí’s friend and patron Edward James, visited Freud in London on 19th July 1938, taking with them not only the painting Metamorphosis of Narcissus, owned by James, but a copy of the article Dalí had written for the journal Minotaure in 1933, ‘Interprétation paranoïaque-critique de l’Angélus de Millet’. Dalí had also been given permission to sketch Freud. Although Dalí was disappointed in his attempt to engage Freud in conversation about his concept of ‘critical paranoia’, he was delighted that Freud admired his painting. Freud was as fascinated by Dalí as Dalí was by Freud: ‘Contrary to my hopes we spoke little, but we devoured each other with our eyes.’ James subsequently described Dalí sketching ‘hastily but accurately into a drawing book’.

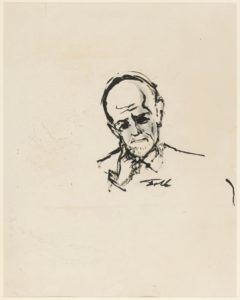

Portrait of Freud by Salvador Dalí, © Salvador Dalí, Fundació Gala- Salvador Dalí, DACS 2018

Three Sketches

The three sketches are quite startlingly different in style and medium. Two are in pen and ink, but of these one is on blotting paper, the other on a page detached from a sketch book. The latter is the one Dalí claimed was done from life, although at first sight it appears unconvincing from this point of view. The third drawing is the one that looks the least stylised and most ‘life-like’ (right). It seems a very direct record, the expression and tilt of the head slightly quizzical. Before we saw the whole object, we thought this had the strongest claim to be done from life. However, on seeing the original we changed our minds. The sketch is on a large sheet of heavy paper, which might be part of a cardboard folder, but occupies only a small part of it; this is not a sheet from a drawing book, as James mentioned. Moreover, it is sketched with a brush and Indian ink, and part of the face is shaded with wash – unlikely therefore to have been made in the conditions of the visit.

Portrait on Blotting Paper

The portrait on blotting paper, which belongs to the Freud Museum London (main image), is lightly drawn in a curious manner, with multiple fine lines creating the contours of the head, thickly clustered in places to create shadow and contrast. Details of features are created with stippling and cross-hatching. Blotting paper, soft and absorbent, is normally used to dry the wet ink of, for example, a letter, so that it bears the trace of another set of marks from another surface, rather than being itself a support for a drawing. To get the fine lines Dalí makes here, avoiding the immediately absorbent character of the paper, demanded a very fine touch, and the effect is almost that of a ghostly imprint, in a manner similar to light-created images on photo-sensitive paper. If the unusual style resembles anything, it is the drawings of Seurat, several of which were reproduced in Minotaure in Spring 1938, just before Dalí saw Freud. Seurat’s drawings, which create the forms of figures, animals, trees etc through dark masses of pencil or charcoal rather than discrete outlines, were on thick, grainy paper, which gives a similar effect to Dalí’s massed lines. Of the three drawings, it could be the one closest to Zweig’s comment that they avoided letting Freud himself see Dalí’s sketch, because it seemed to reveal death in his face.

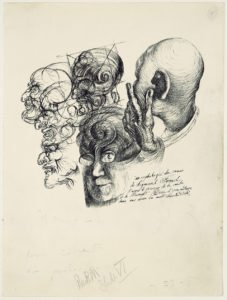

Sketches of Sigmund Freud by Salvador Dalí, 1938, © Salvador Dalí, Fundació Gala- Salvador Dalí, DACS 2018

Pen and Ink

The other drawing in pen and ink is the one Dalí reproduced in his autobiography The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí, with the inscription: ‘“Morphology” of Sigmund Freud’s cranium following the principle of the snail’s spiral (left). Drawing from life two years before his death – Salvador Dalí’. (Freud died just over a year after their meeting, in September 1939, but Dalí was notoriously inaccurate about dates.) Two of the six heads in this sketch show a cranium in the form of a snail shell. In his autobiography Dalí recounts his discovery of ‘the morphological secret of Freud’. Dining one night on snails, he happened to see a photograph of Freud in a newspaper reporting his arrival in Paris; this was hugely exciting news, culminating for Dalí in the ‘discovery’ that Freud’s brain was in the form of a spiral. For Dalí the spiral was the ideal form, related to the measurements of the golden section. This idea informs the sketch on several levels. The head at the centre top of the sketch is roughly outlined with geometrical proportions, hinting at the golden section. The ‘head’ then takes two quite different directions. The eyes of the large head below with snail skull seem to gaze straight at the artist. But the three almost caricatural head-profiles on the left of the drawing refer quite distinctly to one of Dalí’s most revered predecessors – Leonardo da Vinci. They resemble Leonardo’s sketches of the heads of old men, and Leonardo also on occasion would measure the proportions of a head or a figure in a similar way. That Dalí might have had Leonardo in mind during his visit to Freud is not surprising. He was familiar with Freud’s essay ‘Leonardo and a childhood memory’; had reproduced the Leonardo Madonna and Child with St Anne in his essay ‘Interprétation paranoïaque-critique de l’Angélus de Millet’; and was especially fascinated by the double image Freud indicated in the painting which seemed to corroborate his own ‘critical paranoiac’ double images. This drawing, then, may indeed be the one, as Dalí claimed, that was done from life, though the heads perhaps least resemble their subject on the surface. One can imagine Dalí consumed by the connections he perceived between Freud and Leonardo.

‘Dalí-like’

The different artistic identities Dalí assumes in these three sketches are startling. The most ‘lifelike’ is the least ‘Dalí-like’. The other two have visual characteristics recognisably his, but still more strongly recall two very unlike artists, Seurat and Leonardo. Did the encounter with Freud precipitate a kind of identity crisis, in which Dalí veered between the modernism of Seurat and the greatest of the old masters? Or proved he could excel at both?

Professor Dawn Ades, CBE, FBA is Professor Emerita of Art History and Theory at the University of Essex. A Trustee of the Freud Museum London from 2008-2018, Dawn Ades curated the 2018 exhibition, Freud, Dalí and the Metamorphosis of Narcissus, which featured Salvador Dalí’s original painting, The Metamorphosis of Narcissus, on loan from Tate. Dawn Ades has been responsible for some of the most important exhibitions in London and overseas over the past 30 years, including Dada and Surrealism Reviewed, Art in Latin America and Francis Bacon, and the 2017 Royal Academy of Arts exhibition, Dalí/Duchamp.

Freud, Dalí and the Metamorphosis of Narcissus, Exhibition Catalogue

Explore the connection between Sigmund Freud and Salvador Dalí, starting from their one meeting, to which Dalí brought his recently completed painting The Metamorphosis of Narcissus. All purchases support the Freud Museum and enable us to continue to create exhibitions that explore the legacy of Sigmund Freud, Anna Freud and psychoanalysis.