Alice Butler will be running a writing workshop on Kleptomania, Art and Feminism at the Freud Museum this summer. Details >>

She is also giving a reading of her work on Saturday 3 August. Details >>

In memory of kleptomaniacs, hysterics, artists and writers, some dead, some alive: Kathy Acker; Ida Bauer; Louise Bourgeois; Madame de Boves; Sophie Calle; Ella Castle; Hilda Doolittle; Sarah Lucas, and more…

Letter Fragment 1

26 April 1898

This is addressed to those that have cased me,

The doctors, novelists, shopkeepers and policemen (also my husband),

I give you this open letter, so you can finally hear me. The open letter is fair game. Zola used it only three months ago, like he used me. I am using it back.

J’Accuse…!

No doubt you will write all over it. You will flourish the margins with your verdicts, and use it as case evidence. A choking spritz of pathological perfume. You will go away vindicated. Happy with my screams and stutters; that yes, I am hysteric; I am a kleptomaniac. This is what you will think to yourself when you grope the fresh newspaper print. Lower-case and upper-case: an interwoven show of feminine madness personified. You will convince yourself that yes, you got it right: in that case history you published last year. You gave me a name I did not recognise (what was it? was it ‘Eloise?’); you said it was to protect me, kept repeating it. This is what you told yourself and others, the other men that made their cases, from Paris to London.

P for Paris

Walter Benjamin was a poetic, philosophizing consumer of Paris. He talked of the magasins de nouveauté, the glass-roofed passageways that gave way to the dazzling department stores; he saw in these technological spectacles, a metaphor for modernity. He was obsessed with Parisian interiors, mused on the sumptuousness of plush velvet like any other female fetishist. He looked to the city and to the home, walked between them. “Plush,” he says, is “the material in which traces are left especially easily.” P for Paris. P for Plush. P for printing. His fetish for Parisian architectures also coincided with his interest in the work of art in the age of mechanical reproduction.

In that famed essay—but in a far less-quoted section—Benjmain notes how “the growth and extension of the press,” at the end of the nineteenth century, “made new political, religious, scientific, professional, and local journals available to readers,” bringing about a democratic shift whereby readers could turn into writers through the outspoken medium known as the ‘letter to the editor’. In other words: the open letter. My beloved kleptomaniac, using a pseudonym of Eloise, mines it as a source of public disorder, bodily ownership: a way of shifting space, and grabbing space, as her personal experience infiltrates the public sphere.

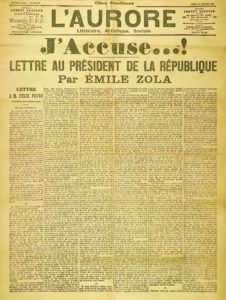

Émile Zola, ‘J’Accuse…!’, L’Aurore, Thursday 13 January 1898. Image: Wikimedia Commons.

“Literary competence is no longer founded on specialised higher education,” Benjamin writes, “but on polytechnic training, and thus is common property.” Accordingly, Benjamin reckons there is Marxist appeal to this opening up of letters, with the claim that “Work itself is given a voice.” I am extending Benjamin’s debate through a feminist lens. In the form of the open letter, women are given a voice. Eloise revises the open letter along her klepto-feminist lines, following the inked protest of Émile Zola (author of The Ladies’ Paradise, in which he penned (and penned in) the kleptomaniacs seduced by the department store), who in 1898 published an open letter in the French newspaper L’Aurore that was addressed to the President of France. In this political, public epistle—simply titled “J’Accuse…!” and given provocative front-page placement—Zola protested the unlawful imprisonment of Alfred Dreyfus, a French Army General Officer sentenced to life-long jail time for espionage.

Letter Fragment 3

My gift, my voice, my story—this open letter. Opposed to his gift, his story—his case history—which I stumbled upon last week, printed in slimy black ink, freshly done but marked forever. It was an unseasonably hot spring day, with not a cloud in the sky, like an endless roll of perfectly steamed blue silk. This moment in April brought a rush of excitement and thrill, a fizzy sensation in my fingertips. Headed for Liberty’s, I was walking down Regent Street from Piccadilly Circus—in the midst of the traffic, as carriages clacked right past me—when I caught sight of the front cover of The Illustrated London News, stacked up high on the corner of the pavement. I pinched it. It was unbound. I remember stiffening a little on the kerb, on the precipice of anger and rage. I froze as I saw a portrait of myself that I could not understand. Thousands of overdressed bodies grazed right past me; they too could not see me. Who was this Eloise? “Ladies, Don’t Go Thieving” ran the headline, spurring all its readers to sing along with glee… “A beauty of the West End went, Around a shop she lingers, And there upon some handkerchiefs / She clapped her pretty fingers.”

The case history followed the ballad; I scanned it quickly, a false document deserves this casual kind of reading. He argued that he’d discovered the sources of my stealing desire: unveiled me. He scoped me out forensically. He thought he knew my insides.

“ELOISE WAS SICK FROM IRREGULAR MENSTRUATION AND WEAKNESSES OF THE BOWEL. THIS EXPLAINS HER PATHOLOGICAL ATTRACTION TO LACE AND SILK. IT ACCOUNTS FOR HER MONOMANIA.”

“ONLY HEARING THE WORD SILK PRONOUNCED, OR MERELY THINKING ABOU IT, WAS ENOUGH TO AROUSE HER.”

“SHE SHOWS SYMPTOMS OF HYSTERIA WITH A NERVOUS TEMPERAMENT AND DISPOSITION.”

“SHE STOLE OUT OF PERVERSE DESIRE. SHE FELT REJECTED BY HER HUSBAND.”

“SHE TOOK THINGS BY CHANCE, SEDUCED BY THE HEADY ATMOSPHERE OF THE DEPARTMENT STORE.”

“HER BEHAVIOUR WAS SYMPTOMATIC OF DRUNKENNESS. SHE SECRETLY TOOK TO THE BOTTLE AT HOME.”

“SHE IS INTENSELY NEUROTIC, RAVAGED BY FURRIOUS, IMPERIOUS NEEDS. THE FITS GOT WORSE, INCREASING UNTIL THEY BECAME A SENSUAL PLEASURE NECESSARY TO HER EXISTENCE.”

“SHE RISKED, UNDER THE EYES OF A CROWD, HER NAME, HER PRIDE, AND HER HUSBAND’S HIGH POSITION.”

He twisted my words as he cased me. He cut up my words as I now cut up his. Let me pick at his texts, and watch his ‘reason’ unravel.

I’d only been married to my husband two weeks when I began spending aimless hours in the afternoon walking the streets of London alone. The city was changing quickly; it felt good to move throughout it, to smell the perfumes in Liberty’s, to finger the ribbons, to see through the fragile lace.

I watched the scene flicker before me as I walked.

Flaneuse then filch

As Lauren Elkin writes in her own reverie on the woman walker: “The rise of the department store in the 1850s and 60s did much to normalise the appearance of women in public.” Eloise is a flaneuse, feeling her way through pavements and passageways, desiring independence, space to walk and breathe, and shop, maybe steal, placing her body right there.

She is an early incarnation of Virginia Woolf’s Clarissa Dalloway, who etches her body into the dazzling chaos of London, digging deep with her heels as she walks the city streets, from Westminster to Piccadilly and on to Bond Street. “I love walking in London,” she says, “Really, it’s better than walking in the country.”

I’ve often wondered how different that novel would be if it began with Clarissa stealing the flowers herself rather than buying them.

delphiniums, sweet peas, bunches of lilac, and carnations, masses of carnations—sweet smells, sweet touch. A ‘case’ of klepto-hysteria.

Letter Fragment 4

My husband, Z, took over my family’s tapestry workshop when we married. He was my father’s apprentice before he died and so I assumed before we wed that he knew his way around a weave. This was the main reason I said yes; it was a purely contractual agreement. It helped that he was an immaculate dresser, who donned waistcoats in deckchair stripes, to match the park furniture of Hyde Park where we walked. He wore silk cravats in all the colours of the rainbow; I could’ve licked them like a lollipop. But this was as far as my desire went to touch him. And while he could stroll and look as good as Baudelaire, he was terrible at tapestry.

And so I found myself accompanying him to Paris in the summer of 1896. He was meeting a wealthy French shopkeeper with an impressive collection of Rococo tapestries, all either incomplete, unfinished or in broken fragments. Z needed my help. He had no idea how to repair them, but he didn’t tell the shopkeeper that. He was an impressive actor, swooning over those tapestries all day, no doubt parroting the historical detail and technical information I had helped him learn the night before. He was often out all day. As soon as I heard him leave, I slipped through the back door of our unbearably hot lodgings and marched to Le Bon Marché.

A warm wind was blowing and had already dried the pavement, after the thunderstorm the night before. The shop was not open for another five minutes. I paused for a moment outside and marveled at the majestic size of the store that dazzled in the morning light.

Shopgirls were arriving in magnificent numbers. I heard their silk ruffles rustle as they angled their bodies in such a way as to fit through the doors of both their palace and their prison. I felt the urge to grab any one of their hands as they shuffled straight past me, madly desiring that I could be taken with them. Pretty things were being swallowed up all the time, a continual cascade of materials flowing with the roar of the river. Waiting for the shop to open, I was ready to jump in, to swim with the endless flow into the basement: silks from Lyons, woollens from England, linens from Flanders, calicoes from Alsace, prints from Rouen.

I wanted to be lost. I wanted to move with no set plan or direction, to wander up and down stairs, round endless corners, along pretty iron worked balconies, with so much time to touch and grope, to dance through open displays. From the hall of ribbons to the umbrella parade to the silk hall on the sixth floor.

Its high glazed ceiling, sumptuous counters, and church-like atmosphere frightened and thrilled me in equal measure. For a moment I forgot myself as I gazed and grazed at the blazing conflagration of silks, gushing and flowing, in light blue, lilac and yellow, fluorescent in the morning light that poured through the top floor windows. I felt intoxicated, a pleasure I did not recognise. Like nothing I had felt before. My fingers trembled with desire. Falling from overflowing shelves, and in boxes which had been torn open, a harvest of silk scarves displayed the brilliant red of geraniums, the milky white of petunias, the shimmering purple of lavender fields. I scrunched it up in my hand; then quickly cleaved it down my corset and into my bosom. In stealing, I could finally breathe, satisfied. Addicted to this freedom, to this time. Thereafter, I took pleasure in trying out a different technique each time. I could magic away ribbons, flounces of lace, embroidered handkerchiefs, into the many gaps and folds of my crinoline. And before you ask—yes, Z dutifully gave me some silver francs each morning; there was money in my purse. But it came from him.

It was not mine.

Unlike this time, this space, and my sweet-smelling, silky-smooth lavender scarf.

Another detail you should know that you probably don’t. Z’s meetings could never have lasted all day, though he came home promptly at 6pm every evening (by which time I had hidden the stolen fabrics inside cushion covers, deep within armchairs, carefully unpicked and promptly resewn). I didn’t care much that Z was clearly having an affair with the shopkeeper’s governess. I dreamt of the shopgirl at the silk counter instead, with flame-red curls pinned neatly to her head. I found another use for my lavender silk, which I rubbed hard closely to my cunt (sweet smells), in the time after returning from the store, after hiding my goods, but before Z returned, shrewdly keen to please me by complimenting my youthful, rouged cheeks. “You look glowing,” he would exclaim when I opened the door.

But by September, the warm summer was over, and I devotedly returned with Z to London, grieving the loss of my hot and steamy paradise. Desperate to not leave all of my possessions behind, I tied ribbons surreptitiously in my hair; kept silk sheathes close to my skin, protected by my undergarments. On the surface I was smiling.

I tried to feel happier by frequenting Liberty’s instead, but here I was less anonymous; I blushed with conspicuous shame—which perhaps explains why, on 5 October 1896, a guard hired to patrol the store seized my shoulder just as I was heading for the door, hands warm and cosy within my freshly stolen sable muff. From there, the scandal unfolded: Z was aghast, thought me crazy and hysteric; I was remanded in Holloway Prison (with rat fur not fox fur); I waited patiently for my trial, plotting which lace dress to wear, and which veil to speak through. I was excited to put on a show—to feed the hungry mouths of the media with morsels of my madness.

Before the trial I was stripped naked and examined. “She is neither mentally nor morally responsible for her crime,” I heard them whisper. “She is weak, diseased; she is a kleptomaniac.” My lawyer, my doctors and my poor, poor husband all trumpeted this narrative. It was hardly unexpected. I was convicted on one count of shoplifting, but freed on the promise that Z would “take charge” of me, have my kleptomania cured.

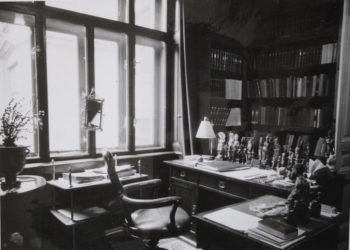

And so after the trial, Z signed me up as a new patient of a mysterious doctor who asked me to lie on his couch and talk. We’ve all seen his verdict on the front cover of The Illustrated London News. What he or Z didn’t realise, though—and which readers I’m telling you now, in this, my own case history—was that the stealing didn’t stop with the treatment. I simply switched locations. After each session in which I talked and talked, spoke of childhood and tapestry, I erupted from his couch, and quickly slipped his miniature figurines that cluttered his mahogany desk into my silk pouch. His bespectacled, bearded face was deep inside his compendium of notes; looked and wrote too hard to truly see me. I escaped, taking pieces of him with me.

I took them home—from my beloved Egyptian Baboon of Thoth to my favourite phallus amulet—and quickly added them to my treasure from Paris, which I’d been hiding in the attic. It was an addiction, a fever, which made me feel unstoppable. Inside an abandoned box of tapestry fragments that Z had given up repairing, I stowed ribbons, scarves, swatches of lace and silk, and my doctor’s tiny ancient artefacts.

Hungry for the time alone that I once had in Paris, I began waking at dawn to retreat to my room in the sky. I cut up corners of candyfloss-coloured crêpe de chine; drilled holes in my new miniatures, sliced off arms and legs. I twisted, plaited and knotted Alencon lace trims to make never-ending ropes that bubbled like sea foam.

I made new shapes from the tapestries, stitched together with stolen ribbons. I found new uses for my stolen goods, a secret, a pleasure I could name.

Feminist Cut-ups

There are many ‘kleptomaniac’ artists and writers that have inspired Eloise’s illicit attic art, from Louise Bourgeois aggressively cutting into material in a paradoxical gesture of repair, to Valerie Solanas declaring a ‘society for cutting up men’ in 1967, to Kathy Acker, stealing de Sade, Dickens and Cervantes, cutting up their words and meshing them up against her own life writing, which detailed sexual experience and violent emotions in exhausting, destabilizing detail.

Writing after them, and speaking through Eloise, I’ve rewritten the form of the case history, to explode the couch into a million tiny threads. I’ve worked with a restless, feminist frame. I’ve cut up objects, texts and history.

Cutting the Couch

In doing so, I’ve also remembered H.D. (1886-1961), the poet, novelist and memoirist, with a sharp bob and penchant for expertly cut blouses, who had analytic appointments with Freud in 1933 (March through May) and 1934 (October through November), and who documented these experiences in published and unpublished pieces. In 1935, H.D. refused to publish her poem “The Master” in her friend Robert Herring’s anthology Life and Letters Today, the reasons for which seem tied to the confrontational tone it harbors towards her doctor. In a similar way to a love letter, H.D. mines the intimacy of the unpublished poem, its protective enclosure, to release angry, feminist feelings. She is raw, exposed and uncoded, writing: “I was angry with the old man / with his talk of the man-strength, / I was angry with his mystery, his mysteries, / I argued till day-break…” From refusal comes lesbian desire: “she is woman, / her thighs are frail yet strong, she leaps from rock to rock.”

I’ve remembered Louise Bourgeois (1911-2010), the artist who loved fur coats, and who was in psychoanalytic treatment, first with Dr. Leonard Cammer in 1951 (a brief affair), and then with Dr. Henry Lowenfeld, for some thirty years, between 1952 and 1980. Lowenfeld, immortalized as “L” in the enigmatic bronze sculpture, Rondeau for L (1963/1990), drove the artist wild with jealousy, rage and desire. Always writing through her psychoanalysis—on thousands of loose sheets documenting thoughts, feelings, dreams, plans, and responses to her reading (in 1952 she writes “Am sick and tired of Freud and Co”), which were found buried deep within her Chelsea home in 2004 and 2010, and exhibited at the Freud Museum in 2012, alongside many of her sculptures—Bourgeois poured it all out on the page. She complains that Lowenfeld is too expensive; that he gives her “housewife” hours: both drives, in her eyes, to make her more subservient to her art historian husband. And yet she stayed with him. Rather than exploding the couch to pieces, Bourgeois “took from it what she needed, when and how she needed it,” as Juliet Mitchell describes. It was always a question of use. Along similar lines, Mignon Nixon notes of Bourgeois’s approach to psychoanalysis and artmaking: “Analysts did not repose on pedestals, and theories were not permitted to rest quietly on her shelf. […] Bourgeois treats psychoanalytic theory as an object to be used.”

I’ve remembered Eve Kosofksy Sedgwick, creating “A Dialogue on Love,” and also an essay, which works through, in a mode of reparative reading akin to Louise Bourgeois, her experience as a “Patient [in] (1992).” She considers her identity as a sick person, mentally and physically and sexually, primarily via the relationship she forms with her therapist, the “big-faced, cherubic” Shannon (a man—unlike her previous flirtations with therapy). Determined for her therapist to be a) a feminist and b) at home with queers; Sedgwick’s asserts that she “can’t encounter only Viennese refugees, don’t event want to.” Snippets of dialogue mesh with snippets of notebook mesh with snippets of poem mesh with more sustained paragraphs. Something about the form captures the twisting talk associated with the clinical setting, which Sedgwick also pictures in physical and emotional terms: “Big chairs flank a sofa bland with patches of pastel. Space not only light with sun and canister-lighting but, if there’s an appreciative way to use the word, lite, metaphysically lite. I’m wondering / whether it reflects / no personality, or / already is one.”

The couch—no personality or is one? Other artists have thought about the significance of the literal plush-to-puckered object in psychoanalysis. As Mignon Nixon explains in the essay “On the Couch,” the couch is a central component in the scene of analysis, often known as the frame. Other aspects play a part, such as the frequency and duration of each session, the dimensions of the room, the ornaments and furnishings, or the gestures of two bodies, but it is the couch that invites the patient to recline, to become submerged in her memories, and most importantly, to not become “visually, or reflectively, entangled” with her analyst, thus maintaining the frame which makes transference.

The artist Sarah Jones began photographing the minimal scenography of the clinical setting in 1997. These rooms are empty, talkless voids, sparsely populated with austere furnishings, not people, nor the archeological finds of Freud’s manic collectomania: just a green pillow and orange rug, or red square of carpet for one’s feet. And in another photograph, a pink blanket has been left scrunched and abandoned on the surface of a royal blue couch, as if a baby has just been kidnapped. Another photographed couch pairs a red pillow with red sheets, which creates an abstract, abject strip of colour against the cream woodchip wall. These painterly photographs have an enigmatic and formal stillness, transferring the transference of the physical space, to the space of the photograph. And yet—however still this object-within-an-object is—that is not say it does not move, that is does not quiver with bodily traces. The crease of a red sheet recalls the restless bottom of a patient, tensing, while in another image, a cracked, emulsioned wall vibrates with the traces of past conversations. I can picture the hands that grabbed at, and then discarded, the sugar pink blanket.

Around the same time, Cornelia Parker got forensically close to Freud, when she got inside the woven, ciggy-smells of his couch, crossed by threads of history and myth. Parker extracted a few feathers from the pillow on which many daydreaming heads once rested, and then photographed them, creating an abstracted and illusory trace of the frame: before it flies away, before it disappears. Parker created a photographic daydream of a daydream in her depiction of an ephemeral feather.

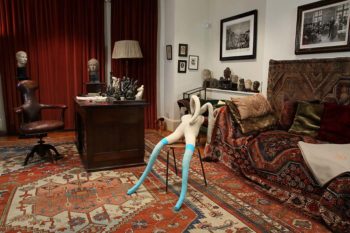

Sarah Lucas created a nightmare. In her 2000 exhibition for the museum, Beyond the Pleasure Principle, Lucas outrageously disrupted the architecture of the frame. Discarded underwear occupied the dining room. Contorted body shapes made from stuffed stockings invaded the study. A blown-up photograph of the artist’s torso, erect nipple face-on, gazed down on the desk from above. These playful and provocative interventions gave meaning to female pleasure unlocked by sheer fabrics. Her principle. And also Eloise’s.

Or in the words of Juliet Mitchell: “The artist or critic is helped by the theory of psychoanalysis to develop the capacity to destroy that theory so that she or he can make use of it.”

In destroying, we also make use with kleptomaniac touches.

Red geranium blood seeps from the cut.

Note: this essay weaves fiction and non-fiction. It is in many ways a speculative history: an act of kleptomania. It steals from novels such as The Ladies’ Paradise and Mrs Dalloway, and it learns from various critical texts that cite the case histories of the time. To give an overview of the medical discourse that led to the kleptomania diagnosis, this essay-story-letter hybrid collects the ideas of multiple psychoanalysts, psychiatrists and physicians that worked on kleptomania and fabric fetishism in the nineteenth century, without fully referencing their differences. Historical figures merge and shift between fact and fantasy.

Alice Butler will be running a writing workshop on Kleptomania, Art and Feminism at the Freud Museum this summer. Details >>

She is also giving a reading of her work on Saturday 3 August. Details >>

Books cut, cited and stolen

Abelson, Elaine S. “The Invention of Kleptomania.” Signs 15:1 (Autumn 1989): 123-143.

Benjamin, Walter. The Arcades Project. Translated by Howard Eiland and Kevin McLaughlin. Cambridge, MA, and London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1999.

———. “The Work of Art in the Age of its Technological Reproducibility: Second Version.” In Selected Writings Volume 3 1935-1938. Translated by Edmund Jephcott, Howard Eiland, and Others. Edited by Howard Eiland and Michael W. Jennings. Cambridge, MA, and London: The Bellknapp Press of Harvard University Press, 2002.

Blau DuPlessis, Rachel and Susan Stanford Friedman. “‘Woman is Perfect’: H.D.’s Debate with Freud.” Feminist Studies 7:3 (Autumn 1981): 417-430.

Bowlby, Rachel. Just Looking: Consumer Culture in Dreiser, Gissing and Zola. New York and London: Methuen, 1985.

Camhi, Leslie. “Stealing Femininity: Department Store Kleptomania as Sexual Disorder.” differences: A Journal of Feminist Critical Studies 5:1 (1993): 26-50.

Elkin, Lauren. Flaneuse: Women Walk the City in Paris, New York, Tokyo, Venice and London. London: Chatto & Windus, 2016.

Larratt-Smith, Phillip, ed. Louise Bourgeois: The Return of the Repressed. London: Violette Editions, 2012.

Miller, Michael B. The Bon Marché: Bourgeois Culture and the Department Store, 1869-1920. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1981.

Kaplan, Louise J. Female Perversions: The Temptations of Emma Bovary. New York: Doubleday, 1991.

Kosofksy Sedgwick, Eve. “A Dialogue on Love.” Critical Inquiry 24:2 (Winter 1998): 611-631.

Nixon, Mignon. Fantastic Reality: Louise Bourgeois and a Story of Modern Art. Cambridge, MA, and London: The MIT Press, 2005.

———. “On the Couch.” October 113 (Summer 2005): 39-76.

O’Brien, Patricia. “The Kleptomania Diagnosis: Bourgeois Women and Theft in Late Nineteenth-Century France.” Journal of Social History 17:1 (Autumn 1983): 65-77.

Woolf, Virginia. Mrs Dalloway. London: Vintage, 2000.

Zola, Émile. The Ladies’ Paradise. Translated by Brian Nelson. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995.