Sarah Lucas

It is as if, with the master gone, those dirty dreams his patients revealed to him with so much shame have come to life, capering through the musty rooms in a lewd parade. Lynn MacRitchie

Sarah Lucas has created a number of new and site-specific works which are installed throughout Freud’s home as follows:

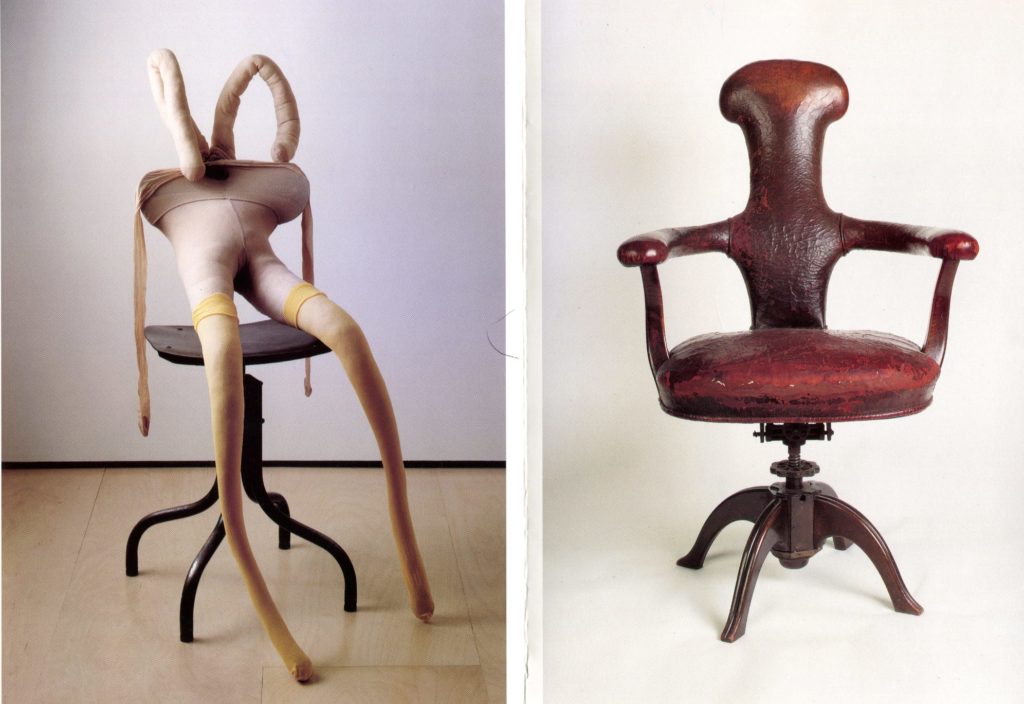

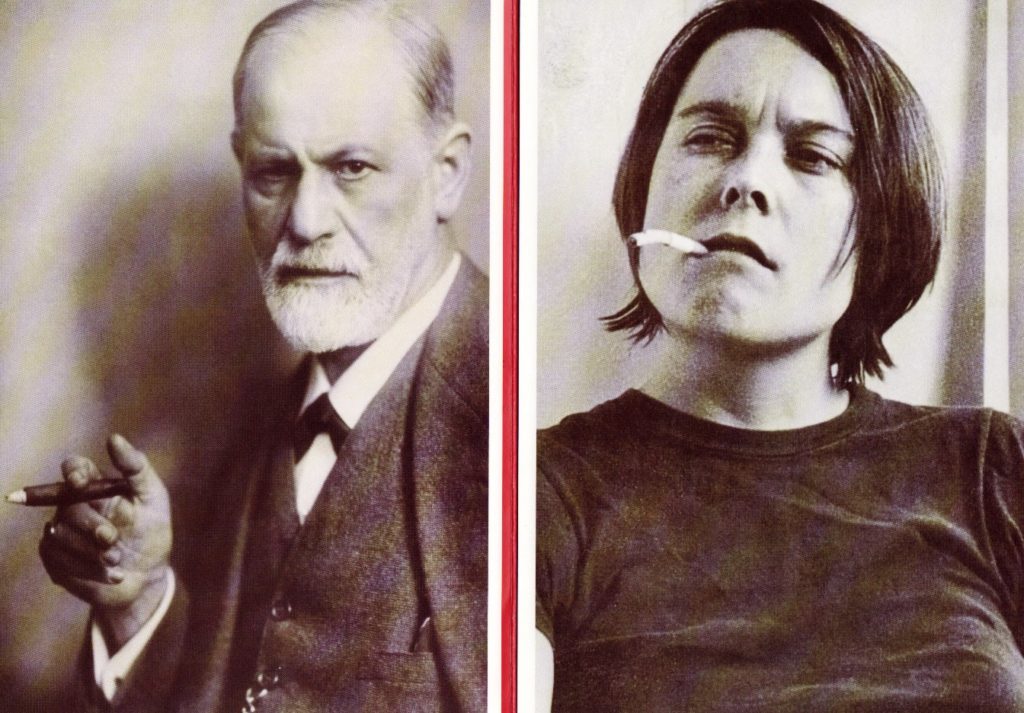

The Study: Hysterical Attack (Eyes)

Hysterical Attack (Mouths)

Prière de Toucher (large photography)

The Dining Room: The Pleasure Principle

The Bedroom: Beyond the Pleasure Principle

Beyond the Pleasure Principle, 2000, Sarah Lucas

Sarah Lucas in Conversation with Curator james Putnam

21 January, 2000

James Putnam: Freud has had an enormous influence on our attitudes towards sexuality and has revolutionised how we think about ourselves. Certainly his great writings like ‘The Interpretation of Dreams’ were the result of much self-analysis. I suppose, in a way, Freud as a person has become almost inseparable from his writings. How do you feel about your particular fusion between self and art?

Sarah Lucas: I’ve never been that keen to separate the person from the work, in fact I always wanted making art to be really close to myself. It suddenly struck me when I was first starting out as an artists, how much attention people put into their appearance every morning. This is not necessarily a vain activity and the result may not be glamourous. You might get up and put on your jeans and think, these jeans just look shit, or the next day you might think they look good. You could wear them for a week and then suddenly think, these just don’t look right, I don’t know why I’ve worn them for a week or two years or whatever. These kind of decisions are going on in our minds all the time. I really wanted making art to be like that, natural, or something to do with how you present yourself.

JP: But some people might dismiss this as merely artistic narcissism or even affectation.

SL: I don’t think its got anything to do with affectation, although it may have something to do with narcissism. Making art in the first place, one way or other, is going to become part of your identity. Even if you make abstract art, for people who know you at the very least, it’s going to be part of your identity that you make abstract paintings. In the same way that you have to put something on or even if you don’t put something on, you can’t avoid the fact you’re making some kind of statement. But the problem with art is how to turn on the tap so that you can have it at your fingertips to actually get on with anything without having these stumbling blocks all the time. How you can turn art into a natural enough thing to be doing.

JP: The whole idea of sexuality in your work, that’s not supposed to be personal is it?

JP: The whole idea of sexuality in your work, that’s not supposed to be personal is it?

SL: It’s not autobiographical or confessional so it’s not personal in that way. I suppose part of my criteria for making a sculpture is to try and be objective or scientific about it. This goes back to the days before I really knew what I might do or how I would know if I had done something of any worth or not. Just because you realise subjective element doesn’t mean it’s not relevant to strike out objectively. But on the other hand, to be concerned with art seen with that separation is still very much a part of what I do. In fact these days there’s a lot of confessional and autobiographical art around so I find myself liking stuff that isn’t even more.

JP: So portraying yourself as coming across with a certain kind of image, or personality an important part of your work?

SL: Year, but I think it’s really the same as everybody does anyway, the real difference is producing this thing which then is separate from you, which does have its own existence in the world. But that is the only difference apart from that it’s the same, a self conscious activity.

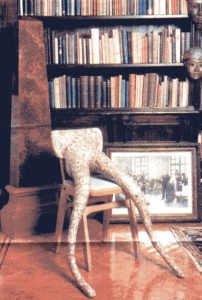

JP: Freud was very interested in the whole area of gender ambiguity, the male and female element in every human being and developed ideas about masculinity complex and penis envy. You certainly tend to come across as rather defiant and masculine in your-self portrait series.

SL: I suppose I’ve always worn the same sort of clothes, like jeans and been kind of boyish before I was even into art but I don’t think I consciously intended to look masculine. In still images, maybe I look more masculine than when I’m moving about. The first self-portrait I made with me eating a banana started out from something I thought would be funny but I didn’t necessarily intend to make an artwork out of it. I just took the pictures and then one of them was really really strong and it turned out that I looked quite masculine, in fact people might not know whether it was a boy or a girl. If I had been standing there in the nude or with make up on, looking girlie, it would have looked like any other picture of someone with a banana that you might see in a porn mag or a Sunday newspaper. But it was the fact that I wasn’t looking like that which gave it its strength, I sort of recognized that.

JP: What do you think about the direct or blatant sexual associations in your work as opposed to the kind of hidden, Freudian type symbolism?

SL: Well I think there are still layers of meaning there might be a lit that’s hidden. I feel that one of the reasons why the directness can be said to be provocative is not because you necessarily know precisely what’s meant which is what happens with the self-portraits. Because their gender is sometimes ambiguous, you’re not quite sure what’s intended, what gives them power, so its still to do with hidden things. But on the other hand I think the directness gives people the way in. I like to be direct, partly because its audacious and honest, both of which I like and also because I think it makes the work more accessible on more levels, to more people.

JP: What do feel about this tendency for people to disregard the significance of the sexual instinct?

JP: What do feel about this tendency for people to disregard the significance of the sexual instinct?

SL: I think that’s completely stupid. I know that from my own experience. All living things, not just animals but also plants, are entirely sexual, as Freud recognised and it seems amazing the lengths people go to to deny that. Like when you’re a teenager you go on a sexual quest for better and better sex or for an orgasm in some cases, and then for more liberated sex as if that’s somehow the answer to the problem.

JP: Do you think that the way that people appreciate your work is linked to that slight embarrassment or repression about open sexuality?

SL: Yeah, I do definitely. It’s not that people are necessarily repressed but I think the embarrassment thing is significant. For example, if you take those early works I made from the pages of ‘The Sunday Sport’, where I blew up the centrefolds. When you see them sitting reading a newspaper on a train it’s a very discreet activity. Viewing them in a gallery is a very different thing especially if you’re walking around with your family or among others, perhaps, people who you don’t know, looking at this stuff, giant-sized. I mean that makes you automatically very self-conscious but I think that embarrassment effect gives the work a lot of power.

JP: So do you think you were concerned with making some social or cultural observation or comment with this work?

SL: I was just trying to do something very immediate from mass produced materials. That’s why I started using these newspapers, I had no money, they were cheap and I could do something with them. Also I was reading various feminist things and reflecting about that kind of stuff, and also thinking about my own attitude towards it. I didn’t have an answer to where I stood on it when I started and what became more and more important was not to have an answer. If you make an artwork you find a form of solution and that’s very concrete but it doesn’t have to be like that. I don’t think it’s the artist’s job and that’s one of the things I discovered with making that kind of work.

JP: So do you see yourself as a very instinctive kind of person and that this aspect comes through in your work, reacting naturally and impulsively to what’s around you?

SL: I think I’m getting increasingly like that and there’s always been an element of it in what I’ve done. Some of the best things have been accidental and quite flippant sometimes. But I’m quite a thinking person and it’s taken a long time to build up to the stage where I’ve really sort of let rip a bit. But although I may have quite a lot of different materials and content available to use in a fairly free way, some of the ideas have actually been a long time coming. I think that’s due maybe to being less instinctive sometimes.

JP: Do you see people’s embarrassed reactions to some of the sexual references in your work as also having a humourous element?

SL: I do find it very embarrassing myself sometimes. Once I’ve made myself something and it becomes concrete and I’ve decided I think it looks good, then I feel quite comfortable in a room with it. But recently when I did an art fair with Sadie (Coles) and I was making some sculptures there with fruit and veg, I became rather self-conscious. Well it’s really only fruit and veg I always say, so why it is so rude? Anyway when I was actually making the sculptures it was a bit like being on stage with an audience, as soon as I started doing anything people were queuing up to see it. Besides the fact that I wasn’t even sure yet whether it would be good or not, jus the rudeness of it became excruciatingly embarrassing for me. But then I observed some of these people’s, particularly women’s, immediate reactions to the finished works. They just laughed their heads off, with both embarrassment and enjoyment. So my reaction is just the same as anyone else’s.

JP: What’s behind the references to smoking in your work both in your self-portrait images and your current use of cigarettes as a working medium?

SL: Well I first started smoking when I was nine. When I first made the picture of me smoking it was a self-portrait with a very long ash. It was supposed to show the grubby side of smoking. Of course you get back a whole sheet of pictures and the only one that’s any good, actually looks quite glamourous. So quite often those thigns are at odds, what actually works as an image and what you might be intending to mean are sometimes conflicting. I first started trying to make something out of cigarettes because I like to use relevant kind of materials. Again, it goes back to this idea of when I’m sitting here in my studio, on my own, smoking, I’ve got these cigarettes around so why not use them. I do that a lot with materials, I might use something just because it’s there, hanging around.

JP: I think there’s an interesting parallel to those references to smoking in your work and Freud’s thoughts about his total addiction to cigars which he claimed he needed for his work. He is even reputed to have compared smoking to what he called the ‘primal addiction’, masturbation. Do you find any affinity with this?

SL: Well, there is this whole oral classification thing with cigarettes but when I’ve put lots and lots of them together in my recent work, I made a new discovery about how they look. You see we may think that we’re living in a certain amount of space and that we think of the air as not being stuff. But when you look at everything under the right kind of microscope you’ll discover that everything is actually solid. When you make something completely covered in cigarettes and see it as solid it looks incredibly busy and it’s a bit like sperm or germs or something. So I always think this is something we could call sexual just in the way taking a cigarette as standing for a small penis is quite sexual.

JP: What do you think about Freud’s view that many obsessive activities are often sexually driven?

SL: Talking about this whole libido thing, I suppose there is this obsessive activity of me sticking all these cigarettes on the sculptures. Part of the thing of using cigarettes came out of the idea of making things out of matches. I was thinking the other day about prisoners. I like the idea that art can’t be taken away from you, even if you have only poor materials. So if you were locked away as a prisoner, there’s still some things you can do and you can formulate and visually manifest and I like that very much. Yet when you think about it in a different way, if you were a prisoner all that kind of obsessive activity could be viewed as a form of masturbation. It is a form of sex, it does not come from the same sort of drive. And there’s so much satisfaction in it, in the same way that there is in the subtler aspects of sex, in that you’re hitting the mark.

JP: Can you tell me about your use of pieces of furniture for sculpture and how you see them in relation to the human form?

SL: It’s really very simple and straightforward. I first started using them as a stand in for bodies in 1992, like a lot of the things I use, because they were cheap, discarded and easily available. The first time I used a table I could visualise it as being a reclining nude. We even call the parts of chairs arms and legs. It’s easy for you to imagine a person sitting in them, as it is in the seat of a car, therefore you can turn them into people in your mind. With soft-furnishings they also take on body shapes according to their fabric with various creases and folds and that can be interesting. I also really like the idea of using a particularly naff piece of furniture and exploring its inherent character or hidden elegance by working on it.

JP: Do you find Freud particularly relevant to what you are all about and do you feel that this occasion of showing your work in his house rather than a conventional art gallery in significant?

SL: From what I know I suppose it’s all relevant. I think that stuff Freud wrote about jokes and their relationship to the unconscious is totally relevant to me. If everything happened through premeditation you wouldn’t get anywhere that you didn’t know about before you started. When you’re making work a lot of the best things happen what way through those kind of slips. And I do see my work interacting in some way with this house. I suppose it’s essentially the whole Freudian thing which is most paramount, both the sexual dimension and the hidden elements. I think people can go and look at the work there because they’ve got all that stuff about Freud in mind. They can actually begin to see some of the broader aspects of my own work that they hadn’t necessarily considered when placed in this context.

Sigmund Freud and Sarah Lucas