Sándor Ferenczi (1873-1933) was one of the most innovative psychoanalysts of his generation.

An early follower of Freud, with whom he also underwent personal analysis, he was instrumental in helping to establish psychoanalysis internationally. Ferenczi was a key figure in the founding of the International Psychoanalytic Association, and was founder of the Hungarian Psychoanalytic Society in 1913.

Sándor Ferenczi made numerous original contributions to psychoanalytic theory and pioneered new, sometimes controversial, techniques that challenged the notion of the analyst as a neutral observer, instead encouraging active and emotive participation in the analytic work. He is remembered today for his compassionate, humanistic approach to therapeutic work.

Sándor Ferenczi being sculpted by Oscar Nemon

Born in 1873 in Miskolc in north-eastern Hungary, Sándor was the eighth of the twelve children of Bernát Fränkel and his wife Rosa, both Jews of Galician origin. He spent much of his upbringing in his father’s bookshop. His father died when he was fifteen years old. After completing his schooling, he studied medicine at Vienna University, receiving his diploma in 1896. After graduating, he spent a year doing his military service before settling in Budapest, where he worked at various hospitals and, in 1900, opened a private practice, while continuing to work as a neurologist and psychiatrist and publishing regularly in Hungarian medical journals.

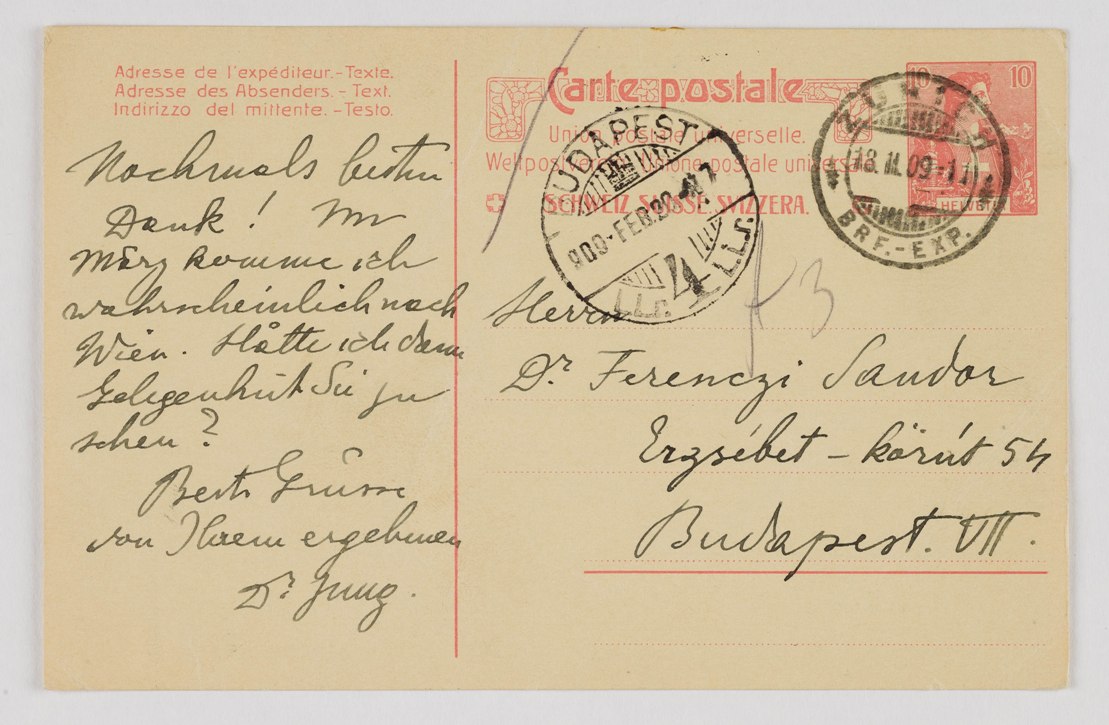

In 1907, Ferenczi became acquainted with psychoanalysis and met Carl Jung. In 1908, he met Sigmund Freud, with whom he became a close collaborator and friend, and dedicated himself to the psychoanalytic movement.

The following year he accompanied Freud and Jung on their trip to Clark University in Worcester, Massachusetts. In 1913 he founded the Hungarian Psychoanalytic Association and coordinated the establishment of the International Psychoanalytic Association and, between 1914 and 1916, was intermittently analysed by Freud.

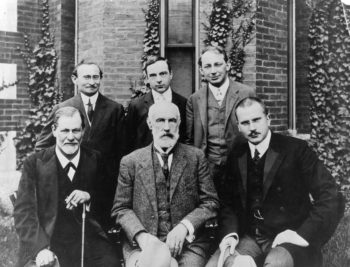

Sigmund Freud, A A Brill, Ernest Jones, Sandor Ferenczi, Carl Gustav Jung and G. Stanley Hall, taken in Worcester, Massachusetts, 1909

From 1912 onwards, Ferenczi was a member of the “secret committee”

During the First World War, he served as a military surgeon, psychiatrist and neurologist in the Hungarian Army, where he used psychoanalysis in the treatment of shell-shocked soldiers, an experience which informed his subsequent ideas on trauma and phylogeny.

In 1918, Ferenczi was elected president of the IPA, but was forced to relinquish the position due to the social and political unrest in Hungary. In 1919, after a long and complicated courtship, Ferenczi married Gizella Altschule, becoming the stepfather of her two children, Elma (whom he had also contemplated marrying) and Magda.

Gizella and Sándor Ferenczi, photographed on holiday

Ferenczi’s early psychoanalytic papers, including ‘Introjection and Transference’ (1909) and ‘Stages in the Development of the Sense of Reality’ (1913), marked him out as an innovator in psychoanalytic theory. From around 1919, he began to he began to develop what became known as ‘active’ technique, according to which the psychoanalyst plays a less passive, more emotive role in the analytic session, initially in order to cultivate transferential dynamics in patients whose treatments were stagnating.

These technical innovations and subsequent ones, while initially supported by Freud, were vigorously opposed by the several prominent psychoanalysts who saw them as serious deviations from Freudian psychoanalysis, resulting in a growing rift between Ferenczi and the mainstream psychoanalytic community.

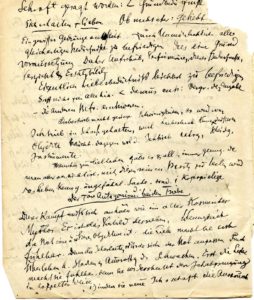

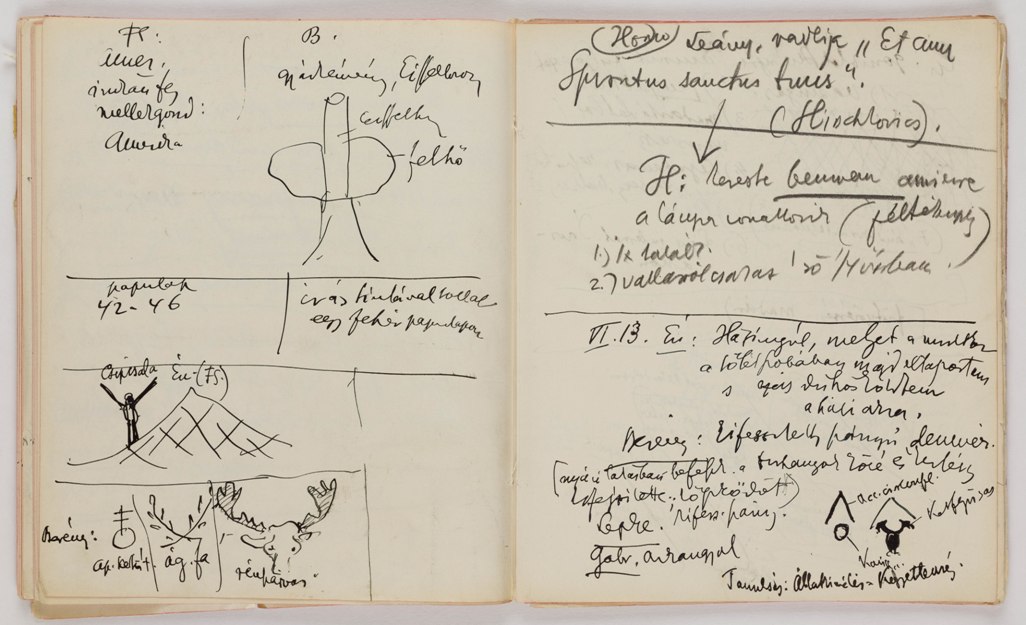

A page from Ferenczi’s clinical diary

Nonetheless, he continued to publish numerous papers: in 1924, with Freud’s encouragement, he published ‘Thalassa: A Theory of Genitality’, in which he introduced the notion of ‘bioanalysis’. Also in 1924, Ferenczi and Otto Rank published ‘The Development of Psychoanalysis’, which was strongly condemned by figures such as Ernest Jones and Karl Abraham, and subsequently by Freud himself. Ferenczi had developed a technique which sought to return to the patient the love that he or she had not received in childhood, leading him to endorse physical contact such as kissing and caressing, and ‘mutual analysis’ (examples of which he committed to his 1932 clinical diary).

In 1926, Ferenczi travelled to America, where he lectured on psychoanalysis and conducted several analyses. Upon his return in 1927 his relationship with Freud, who increasingly expressed his disapproval of the direction of his psychoanalytic thinking and his interactions with patients, began to break down. In 1932, the year in which Ferenczi delivered his controversial paper on ‘The Confusion of Tongues Between Adults and the Child’, their friendship ended. Ferenczi died of pernicious anaemia the following year.

More information can be found at the website of The International Sándor Ferenczi Network

The Ferenczi Archive at the Freud Museum London

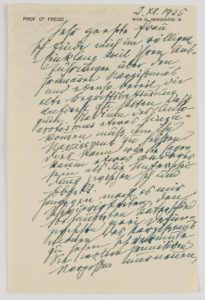

One of Freud’s many letters to Ferenczi

In 2013 the Freud Museum received a donation of an important archive of letters, manuscripts, notebooks and photographs related to the life and work of Hungarian psychoanalyst Sándor Ferenczi. The archive, which includes Ferenczi’s clinical diary and a number of unpublished documents, is of great significance to the history of psychoanalysis.

The story begins in Budapest in 1945. During the final winter of World War II, Budapest was siege from the Soviet Army. After the siege ended, the psychoanalyst Ilona Felszeghy visited the former home of Sándor Ferenczi, only to find it almost completely destroyed by the bombings. Scattered on the floors were manuscripts, letters and papers handwritten by Ferenczi and his colleagues. Felszeghy gathered them up and took them home.

The papers were passed on to Michael Balint, Ferenczi’s literary representative, when he next visited Budapest in 1948 in an attempt to find his own family. Balint had left Hungary for England in 1938, taking with him Ferenczi’s clinical diary and all the letters written from Freud to Ferenczi. These papers and more had been collected Ferenczi’s wife, Gizella, with the aim of publication when possible.

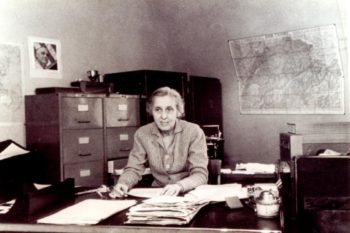

Elma Laurvik, Ferenczi’s step-daughter, in her office

Ferenczi’s step-daughters, Elma and Magda, were also involved in the safe-guarding of his legacy. With constant delays to publication, they were concerned about the archive’s position after their and Michael Balint’s deaths. The proposed Balint chose Dr Judith Dupont, a lifelong friend of theirs, as his successor. Dr Dupont, a psychoanalyst in Paris, was interested in Ferenczi’s work and had translated Thalassa into French.

Vilma Kovács’ portrait in Ferenczi’s collection

Dr Dupont was born in 1925 in Budapest and comes from a family with strong links to psychoanalysis in Hungary: she is the granddaughter of Vilma Kovács, who trained as a psychoanalyst under Ferenczi, and the niece of Michael and Alice Balint, who were both leading psychoanalysts. In 1970 the archive came to Dr Dupont, who set to work translating and publishing various parts.

In 2012 Dr Dupont officially donated the Ferenczi archive to the Freud Museum London, where it can be consulted and studied alongside the archive of Sigmund Freud.

The Freud Museum is committed to preserving the Ferenczi archive and making it available to all who wish to view it. The complete archive, as well as the Museum’s extensive archive of documents related to Sigmund and Anna Freud, is accessible by appointment. The archive catalogue can be searched here. For appointments please contact [email protected]

Sándor Ferenczi’s notebook

Friends and colleagues gather for Sándor Ferenczi’s 56th birthday dinner, 1929

Postcard from Carl Jung to Sándor Ferenczi