Because psychoanalysis is a serious business, it has become a classic target of cartoonists.

Freud said that cartoons represent “a rebellion against authority, a liberation from the oppression it imposes”. On the Couch documents nearly 80 years of this rebellion.

Freud said that cartoons represent “a rebellion against authority, a liberation from the oppression it imposes”. On the Couch documents nearly 80 years of this rebellion.

Since The New Yorker published its first “psychoanalytic” cartoon in 1927, its cartoonists have continually renewed the topic within the context of their own times. This exhibition presented “the shrink and the shrunk, the practitioner and the practiced upon…” as they were represented in cartoons from the archives of The New Yorker. After their first outing in New York 80 years’ worth of American couches came home to roost around the original psychoanalytic couch at the Freud Museum.

The exhibition was centered around five main themes: “The Doctor/Patient Relationship”, “The Couch”, “Beyond the Couch”, “Off the Wall” and 2Cartoons Then and Now”

The Doctor/Patient Relationship

Many psychoanalysts stress that the relationship between the patient and therapist is crucial to the cure. The psychoanalyst should abstain from Judgment and take seriously whatever the patient says. Patients are encouraged to speak what is on their minds without censorship or self-criticism and, of course, whatever is said in the analyst’s office is held in the strictest confidence. The urge to play on this trusted, almost sacred, relationship between the analyst and the analyzed has long proved irresistible for New Yorker cartoonists, who often portray the therapist as untrustworthy, condemnatory, arrogant, or just plain nuts.

The Couch

In the minds of many, the psychoanalyst’s couch embodies the very notion of “psychotherapy.” In a traditional psychoanalysis session, patients lie on the couch, facing away from the therapist seated behind them – an arrangement intended to encourage spontaneity and openness. In the hands of New Yorker cartoonists, the couch also serves as a setting for countless comical situations depending upon who lies on (or under) it, who they are lying with, how the occupants behave, and where the couch is located.

In the minds of many, the psychoanalyst’s couch embodies the very notion of “psychotherapy.” In a traditional psychoanalysis session, patients lie on the couch, facing away from the therapist seated behind them – an arrangement intended to encourage spontaneity and openness. In the hands of New Yorker cartoonists, the couch also serves as a setting for countless comical situations depending upon who lies on (or under) it, who they are lying with, how the occupants behave, and where the couch is located.

Beyond the Couch

The cultural phenomenon that is Freudian therapy has become increasingly widespread with the passing of time. No longer is talk of neuroses confined to the analyst’s office; in the hands of New Yorker cartoonists the ideas uncovered in the therapy setting have wandered off the couch and into the world at large. Be it restaurants, playgrounds. socialite parties, or Hollywood film sets. Psychoanalysis seems to have invaded nearly every setting and activity.

Off the Wall

New Yorker cartoonists have always had a penchant for the absurd. Once the standard codes of psychoanalysis-themed cartoons started to wear thin, artists began to employ improbable mixtures of humans and animals, historical figures, and other bizarre personages, proving that one can never guess who they may encounter “on the couch.”

Cartoons Then and Now

The New Yorker’s first cartoon foray into the realm of psychotherapy appeared in the April 30, 1927 issue, two years after the magazine’s founding, with Peter Arno’s depiction of King Henry VIII revealing his dreams to a shocked psychoanalyst.

Over the next decades, the magazine published two to four cartoons on the theme each year. These tended to focus on the core components of Freud’s newly introduced theories, particularly dream analysis, the Oedipus complex, and repressed sex drives. Over time, cartoons on the practice of psychoanalysis began to appear with greater frequency as knowledge of Freudian therapy — its methods and catchphrases — became more widespread. During the heyday of psychoanalysis, the 1940s through the 1970s, the magazine ran between eight and fifteen cartoons annually.

The cartoons of recent years have come a long way from the early glimpses at life on the couch presented by Arno and others in the 1920s and 30s. Psychoanalysis has effectively merged with the humorous aspects of modernity, and cartoonists relish the opportunity to poke fun at technological and social advancements such as computers and television as well.

Psychoanalysis is not short term therapy; it takes time to explore the complex layers of feeling and experience that make up a patient’s history and serve as the basis for their neuroses. Most therapists advocate three or four hour-long sessions per week, often extending for five or more years. And since psychoanalysis demands a substantial investment of time, it also calls for a substantial investment of money. This fact has irked patients and puzzled outsiders since psychoanalysis first arrived on the scene, but has delighted cartoonists who reference the clichés of the overpaid therapist and the seemingly lifelong commitment to therapy.

Psychoanalysis is not short term therapy; it takes time to explore the complex layers of feeling and experience that make up a patient’s history and serve as the basis for their neuroses. Most therapists advocate three or four hour-long sessions per week, often extending for five or more years. And since psychoanalysis demands a substantial investment of time, it also calls for a substantial investment of money. This fact has irked patients and puzzled outsiders since psychoanalysis first arrived on the scene, but has delighted cartoonists who reference the clichés of the overpaid therapist and the seemingly lifelong commitment to therapy.

The cartoons selected for On the Couch are organized into eight categories based on subject. These categories are:

The Early Years

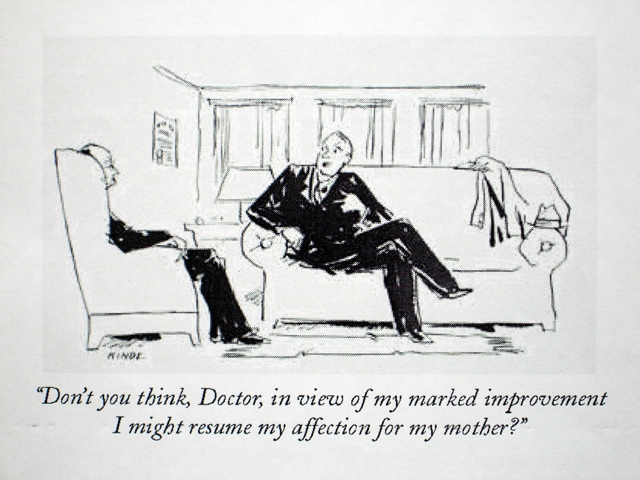

Following the 1927 cartoon featuring Henry VIII, the cartoon gag lines tended to revolve around Freudian notions that had just become fashionable, such as “affection for my mother,” the unmentionable dream or the free-associating mind.

The Couch

This all-important piece of furniture becomes the setting of countless comic situations involving who lies on it or under it, accompanied by the analyst or alone, overexcited or asleep, etc. “Like a desert island with the lonely palm tree,” says New Yorker cartoonist Paul Peter Porges, “the Freudian couch has become a cliché: Both are visually funny and show absurd situations.”

The Jargon

New Yorker cartoonists are masters of the art of the brief caption, and they pioneered the wordless joke. Given that talk prevails in the psychoanalytic situation, however, many have been inspired to satirize the professional jargon, be it old-fashioned or postmodern mumbo-jumbo (“…you deconstruct your childhood, and then you die.”). In 1948 a prescient drawing by Whitney Darrow, Jr. depicted as very odd something which decades later would become standard procedure: a whole family submitting itself to analysis.

Here, There and Everywhere

The ubiquity of Freudian therapy as a cultural phenomenon is characteristic of the postwar golden era of psychoanalysis. Restaurants, kindergartens, film sets, going on vacation or staying at home – psychoanalysis seemed to have invaded nearly every setting or activity imaginable, and vice versa. “Would the patient kindly sign the release form for a sitcom?”

Who’s Nuts?

One of the oldest clichés is that analysts are at least as crazy as their patients, or just as incompetent, or simply no less human. Cartoonists have been delighted to embrace this view and discover new angles in it.

Time and Money

Analysis is expensive, a fact which has irked patients and puzzled outsiders (why would someone get paid so much for hardly ever saying a word?). As far as the therapist is concerned, this resistance calls for careful analysis. To the cartoonist it’s a godsend.

Not Funny Anymore

Sometimes aggression towards depth therapy is not hidden at all. Quite a few New Yorker cartoons focus on the analyst as either a target or an agent of hostility.

Culture Clashes

New Yorker cartoonists have always had a penchant for the absurd. Once the standard codes of psychoanalysis started to wear thin, strange combinations of humans and animals, witches, sarcophagi and other improbable situations made an appearance. When Eldon Davis revisits Henry VIII in 1971, this same monarch is being manipulated by a therapy-wise wife. And in a more contemporary example, David Sipress delivers the final word on Freud’s assertion that psychoanalysis is a never-ending affair…

Cartoons of the New Yorker

The Early Years

Following the 1927 cartoon featuring Henry VIII, the cartoon gag lines tended to revolve around Freudian notions that had just become fashionable, such as “affection for my mother,” the unmentionable dream or the free-associating mind.

The Couch

This all-important piece of furniture becomes the setting of countless comic situations involving who lies on it or under it, accompanied by the analyst or alone, overexcited or asleep, etc. “Like a desert island with the lonely palm tree,” says New Yorker cartoonist Paul Peter Porges, “the Freudian couch has become a cliché: Both are visually funny and show absurd situations.”

The Jargon

New Yorker cartoonists are masters of the art of the brief caption, and they pioneered the wordless joke. Given that talk prevails in the psychoanalytic situation, however, many have been inspired to satirize the professional jargon, be it old-fashioned or postmodern mumbo-jumbo (“…you deconstruct your childhood, and then you die.”). In 1948 a prescient drawing by Whitney Darrow, Jr. depicted as very odd something which decades later would become standard procedure: a whole family submitting itself to analysis.

Here, There and Everywhere

The ubiquity of Freudian therapy as a cultural phenomenon is characteristic of the postwar golden era of psychoanalysis. Restaurants, kindergartens, film sets, going on vacation or staying at home – psychoanalysis seemed to have invaded nearly every setting or activity imaginable, and vice versa. “Would the patient kindly sign the release form for a sitcom?”

Who’s Nuts?

One of the oldest clichés is that analysts are at least as crazy as their patients, or just as incompetent, or simply no less human. Cartoonists have been delighted to embrace this view and discover new angles in it.

Time and Money

Analysis is expensive, a fact which has irked patients and puzzled outsiders (why would someone get paid so much for hardly ever saying a word?). As far as the therapist is concerned, this resistance calls for careful analysis. To the cartoonist it’s a godsend.

Not Funny Anymore

Sometimes aggression towards depth therapy is not hidden at all. Quite a few New Yorker cartoons focus on the analyst as either a target or an agent of hostility.

Culture Clashes

New Yorker cartoonists have always had a penchant for the absurd. Once the standard codes of psychoanalysis started to wear thin, strange combinations of humans and animals, witches, sarcophagi and other improbable situations made an appearance. When Eldon Davis revisits Henry VIII in 1971, this same monarch is being manipulated by a therapy-wise wife. And in a more contemporary example, David Sipress delivers the final word on Freud’s assertion that psychoanalysis is a never-ending affair…