A rough but not inadequate analogy to this supposed relation of conscious to unconscious activity might be drawn from the field of ordinary photography. The first stage of the photograph in the ‘negative’; every photographic picture has to pass through the ‘negative process’, and some of these negatives which have held good in examination are admitted to the ‘positive process’ ending in the picture.

– Sigmund Freud

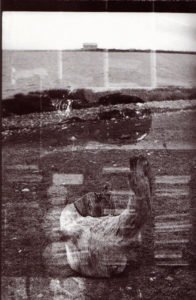

Sambo & Freud, the first exhibition of photographs to be held at the Freud Museum, came about as the result of an accident. Walker took a series of photographs of the grave of a young black man, Sambo, the servant of a ship’s captain who had died near Sunderland Point in the North East of England in 1736. Because he was not a Christian he was buried in a field overlooking a desolate shoreline. A week later Walker came to the Freud Museum where he took a series of photographs, which by accident were transposed over the scenes of Sambo’s grave. The images that resulted from this juxtaposition are suffused with a strange surreal atmosphere and touched with the poignancy of loss and exile.

Sambo & Freud, the first exhibition of photographs to be held at the Freud Museum, came about as the result of an accident. Walker took a series of photographs of the grave of a young black man, Sambo, the servant of a ship’s captain who had died near Sunderland Point in the North East of England in 1736. Because he was not a Christian he was buried in a field overlooking a desolate shoreline. A week later Walker came to the Freud Museum where he took a series of photographs, which by accident were transposed over the scenes of Sambo’s grave. The images that resulted from this juxtaposition are suffused with a strange surreal atmosphere and touched with the poignancy of loss and exile.

A Note on the Exhibition

by the artist

Sunderland Point is a spit of land between the river Lune and the sea, downstream from Lancaster. To get there, you drive along a causeway over the mudflats; if you then walk across the peninsula you come to a long flat shore, facing out across the Atlantic Ocean. To the north, the square block of Heysham Nuclear Power Station squats on the horizon. It is a lonely place.

In the early 18th century, however, Sunderland Point was a major port for ships coming across the Atlantic – before the expanding trade moved to Lancaster itself and then to Liverpool. In 1736, a young black man named Sambo, the servant of a ship’s captain, landed here. But he fell ill and died, and because he was not a Christian, his body was buried in the corner of a field on this coast. Where his grave is still to be found – a brass plaque set in the grass, marked by a wooden cross: “SAMBO R.I.P.”.

In the early 18th century, however, Sunderland Point was a major port for ships coming across the Atlantic – before the expanding trade moved to Lancaster itself and then to Liverpool. In 1736, a young black man named Sambo, the servant of a ship’s captain, landed here. But he fell ill and died, and because he was not a Christian, his body was buried in the corner of a field on this coast. Where his grave is still to be found – a brass plaque set in the grass, marked by a wooden cross: “SAMBO R.I.P.”.

One Christmas, I was visiting my family in Lancaster and on the morning of Christmas day itself, I drove over to Sunderland Point. I walked across to Sambo’s grave, photographed it and came back to the car – to discover that the causeway back to the mainland was now under water. I had to wait four hours until the tide went down and I could go back for Christmas dinner.

A couple of weeks later, I was in London visiting the Freud Museum in Hampstead. I walked in from the tree-lined street, into the extraordinarily darkened room. And there I photographed the collection of antiquities, the bust of Freud himself and on the other side of the rope barrier, the desk, the oriental rug, the couch. All those objects that Freud, in 1938 at the age of 82, was allowed to bring with him when he chose exile from his native Vienna in the face of Nazi persecution.

I developed the film I shot that day, only to discover it was double-exposed: images made around Sambo’s grave merged with images made in Freud’s study. I was annoyed. Two perfectly good sets of pictures had been ruined. But much later, telling the story to friends, I came to realize what an extraordinary conjunction this is. A bed and a grave, two sets of cultural memories, two histories, two excavations. Two exiles two centuries apart which can almost represent a condensed history of Britain as a crossroads of exile, for both good and bad. If Sambo was exiled to this shore through the malevolent power of British colonialism, Freud chose to come to London to “die in freedom”.

Although I would never have deliberately set out to superimpose these two sets of images, it strikes a chord that I’ve discovered them as I’m finishing my research into the Surrealist perception of photography. For the Surrealists were intrigued by the way that the medium could be both factual and magical at the same time, so that when the ‘marvellous’ did erupt within a photograph, that effect was heightened rather than diminished by the physicality of the medium. One might go further and suggest that the magic is there, not in spite of, but because of the factuality – even that the strange things which occur in cameras happen because the camera also has an ‘unconscious’. I don’t feel I made these pictures – my camera did.

Although I would never have deliberately set out to superimpose these two sets of images, it strikes a chord that I’ve discovered them as I’m finishing my research into the Surrealist perception of photography. For the Surrealists were intrigued by the way that the medium could be both factual and magical at the same time, so that when the ‘marvellous’ did erupt within a photograph, that effect was heightened rather than diminished by the physicality of the medium. One might go further and suggest that the magic is there, not in spite of, but because of the factuality – even that the strange things which occur in cameras happen because the camera also has an ‘unconscious’. I don’t feel I made these pictures – my camera did.

To see the pictures in the Freud Museum feels like a kind of homecoming. Here they hover around the walls of the room directly above Freud’s study. As if the couch were dreaming them, perhaps.

But only half a homecoming, at best. For, 250 miles to the north, another tide flows in, and Sambo sleeps on his corner of a foreign field.

Ian Walker