These paintings inhabit the seemingly minor interstices of childhood experience to remind and confront the shades and memories of them. For they are still held, somewhere echoing inside the adult. Through attention to the ordinary I seek to animate these intimate and vivid worlds, lying bare the prosaic memories that childhoods so frequently hold in common. The Childhood Fragments have become a painted tragicomedy of internal narratives and moments holding vulnerabilities and worries, confusions and delights, mischiefs and enthusiasms. These commonplace bits and pieces of experience are at once unexceptional and yet precious. Children everywhere, live a life packed with emotional force. Small things may have overwhelming importance to them. For me painting holds its meaning and value as essentially a contemplative and intimate language

– Helen Wilks

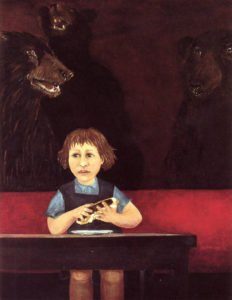

The Gamut, 1999, Helen Wilks

Childhood and the child’s psychic development on the often torturous path to adulthood were central themes in Sigmund and Anna Freud’s work. Helen Wilks paints vibrant canvases describing the pleasures and pains of childhood, and it seemed entirely appropriate to exhibit them at 20 Maresfield Gardens where Anna Freud held so many seminars on child development and on the psychoanalytic treatment of children. In Childhood Fragments Helen Wilks investigate, with great sensitivity, the feelings of children as they try to make sense of the often contradictory world of adults.

Her work investigates the feelings of children as they try to make sense of the world of adults. She explores their exuberant world of fantasy that becomes so easily blunted as the child matures into adult. Her acute observations of the pleasures and pains of childhood in her remarkable paintings are appealing both to adults and children. They create a meeting ground and talking point for shared experiences and provide a means for visitors to reflect on how the events of childhood continue to have an impact throughout her life.

The paintings invite us to remember the buried memories of childhood and some of those disturbing feelings we though we had jettisoned with our toys.

A Note on the Exhibition

Artist Statement

by Helen Wilks

“People are my landscape” – Isaiah Berlin

People have long been my own preoccupation and “landscape”. During the eighties and beyond I painted people absorbed in the vulnerable task of pretending to be other people. Since 1990 this focus has changed. In the series of paintings entitled Childhood Fragments I myself have been the actor (painter) inhabiting memory to unravel an ordinary but particular past in order to reveal an inner present.

The Bears, 1998, Helen Wilks

These commonplace bits and pieces of experience are at once unexceptional and yet precious. Children everywhere, no matter in what situation or circumstance, live a childhood packed with vivid emotional force. Small things may have overwhelming importance then. It is inside this microcosm we grow and fight our way until adulthood cloaks our memory of it and requires of us the use of perspective.

Although writers, in particular, have richly plumbed this remembered world, it interests me that visual artists (with the exception of some film-makers) have tended to merely observe or imitate its doings. Neither of these paths seem to me entirely adequate, possible or satisfactory.

These Childhood Fragments began as images and situations rooted in my own experience. I had to be very literal in certain ways and to make the formal decisions subordinate. The settings were bare because my memories were principally interior feelings matched with a very limited visual image. I kept painting until the image on the canvas had the right psychological presence. It was the personality that mattered, not who it looked like. “I”, though the source, eventually became unimportant.

As the series has progressed, these inhabited memories have become animated by other possibilities and preoccupations: Stories and narratives; figurative illusions; literary and textual connections; abstract constructions; perspectives and scale; and an overriding interest in painting voids the drama of the painting’s edge. (It seems to me that the figurative painting tradition has often been conservative and unadventurous in the confining of the painting’s subject to within the visible frame.)

Some of the later paintings use allusions from other paintings: Dragons not shrimp quotes directly from both Hokusai and Uccello; Juniper bush has its formal structure rooted in an examination of the painting Tobias and the Angel from the workshop of Verrocchio; Frog alludes to two different common stories; Icarus boy quotes from Breugel and from Auden. Relies on Russian icon painting for its configuration, Indian miniature painting and memory for its sense of place, and transmutes the pleasure in childhood balancing to the idea of (nearly) flying. All of which combine to provide an allegory for trying, or the act of painting itself.

For me painting now holds its meaning and value as essentially a contemplative and intimate language providing a means of expression that is as rich, complex, delicate and powerful as any. Despite all other means available it is still, in its own terms, as risky, dramatic and adventurous as any and can (and must) be honestly made. It can invent realities, tell several stories all at once, puzzle and leave the verdict undecided or it can amuse, delight or make the heart ache. Paintings, once they are done, leave a visual springboard for invention in the viewer’s mind.

Helen Kiersnianski Wilks