An exhibition on Freud as archaeological literary critic

When the surrealists opened an art gallery in Paris in 1937, they called it Gradiva. This was a tribute to Freud and his essay ‘Delusions and Dreams in Jensen’s Gradiva’ (1907) – the first psychoanalytic study of a work of literature. The title of Jensen’s book referred to a Roman bas-relief of a walking woman. For the surrealists this figure symbolized the mystery of dreams, sexuality, amour fou. But Freud used the book as an example of the return of the repressed, the compromise of neurotic symptoms and the psychoanalytic cure.

When the surrealists opened an art gallery in Paris in 1937, they called it Gradiva. This was a tribute to Freud and his essay ‘Delusions and Dreams in Jensen’s Gradiva’ (1907) – the first psychoanalytic study of a work of literature. The title of Jensen’s book referred to a Roman bas-relief of a walking woman. For the surrealists this figure symbolized the mystery of dreams, sexuality, amour fou. But Freud used the book as an example of the return of the repressed, the compromise of neurotic symptoms and the psychoanalytic cure.

Freud often compared psychoanalysis to archaeology. His collection of antiquities shows his own fascination with the ancient world. Jensen’s novella Gradiva is about an archaeologist obsessed by an antique sculpture. The subject itself attracted Freud. He also found in the book a poetic depiction of repression and sexual neurosis and, above all, how they were resolved. The cure was through transference – the process by which the patient’s feelings for a significant figure are transferred onto the analyst – a “cure through love”.

Repression

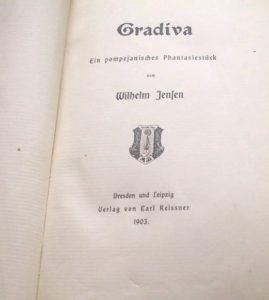

In 1903 Wilhelm Jensen published a novella entitled Gradiva. Its hero, the German archaeologist Norbert Hanold, falls in love with the Roman bas-relief of a walking woman. He names her Gradiva (‘the girl stepping forward’). On a visit to Pompeii, in a “strangely dreamy condition” he meets a woman who seems to be this Gradiva. Eventually he comes to realize that she is in fact his childhood sweetheart, Zoe Bertgang, whom he had failed to recognize.

Freud’s study of this book, ‘Delusions and Dreams in Jensen’s Gradiva.’ (1907), psychoanalyzes its fictional hero. Freud reveals that coherent unconscious motivations guide his behaviour and dreams. The author himself, Freud deduces, wrote under the influence of his own unconscious drives.

Freud’s study of this book, ‘Delusions and Dreams in Jensen’s Gradiva.’ (1907), psychoanalyzes its fictional hero. Freud reveals that coherent unconscious motivations guide his behaviour and dreams. The author himself, Freud deduces, wrote under the influence of his own unconscious drives.

Hanold’s delusion about the Gradiva figure is the consequence of severe sexual repression: “Marble and bronze alone were truly alive for him; they alone expressed the purpose and value of human life.” But what is repressed will inevitably return: Jensen’s book is subtitled “A Pompeiian Fantasy” and its setting in Pompeii offered

Freud a poetic demonstration of his own ideas:

“There is, in fact, no better analogy for repression, by which something in the mind is at once made inaccessible and preserved, than burial of the sort to which Pompeii fell victim…”

Dream

In the Interpretation of Dreams (1900) Freud had shown that there is no sharp frontier between normal and abnormal thought. In dreams we all think “pathologically” under the influence of unconscious desires. Gradiva offered Freud a chance of making psychoanalytic ideas accessible and acceptable by showing them implicit in a work of popular fiction.

In a dream Hanold saw the living Gradiva in Pompeii in 79 AD, overcome by the eruption of Vesuvius and turned into an ashen corpse. Behind this “manifest content” Freud showed that the “latent content” of his dream was telling another story – of his desire to turn the statue back into the living girl it actually represented, his childhood sweetheart Zoe Bertgang.

Hanold had chosen archaeology as a retreat from love. But it was an archaeological object, the sculpture of Gradiva, that aroused his desire. Thus his repressed sexuality used the very instrument of its repression (archaeology) to gain access to consciousness. The symptom of his disorder, the delusion that the sculpture was a real woman, was a compromise formed between the sexual drive and the repression.

A dream gave access to this unconscious process. A forgotten childhood memory of playing with Zoe had turned into a fantasy of having once lived in Pompeii, and this created the delusion that a dead sculpture was alive.

Delusion

Delusion

What first absorbed Hanold’s attention was the curious angle of Gradiva’s raised right foot in the sculpture. This led him to study the feet of real women as they walked. One day he thought he saw his Gradiva alive, walking in his German town. It was then he decided to travel to Pompeii on the pretext of study, but actually to escape his fear of – and his desire for – the real woman.

In Pompeii honeymoon couples disturb his peace and are transformed into a dream of Apollo lifting up Venus and laying her on a creaking carriage. In flight from love, wandering the streets of Pompeii, Hanold encounters his Gradiva. Though she speaks German to him and encourages their conversations, he still cannot believe she is real. He also meets a naturalist catching lizards in the sun. These experiences are “condensed” together: Gradiva returns to him in a dream, as a lizard-catcher sitting “somewhere in the sun”.

Recent memories or “day-residues” are used by dreams, as are plays on words. The real Gradiva, Zoe Bertgang, was staying “in the sun”, at the Albergo del Sole (Sun Hotel), while the naturalist was her real father. Though Hanold still failed to recognize her, she knew him and played along with his delusion. In all delusions there is a grain of truth. His real feelings for Zoe had simply been displaced onto the Pompeian Gradiva. Her sympathy was a necessary instrument to transfer them back to their real object.

Cure

Cure

At the end of Jensen’s Gradiva Hanold is cured by Zoe. Through her patient sympathy with his delusion, she reveals that Gradiva was a disguise for his childhood love for her. When he realizes she loves him, his own repressed love for her is liberated.

In his study of the book Freud takes us through the stages of a psychoanalytic cure. Some part of the patient’s desire had combined with resistance to form a delusion: the treatment consisted in giving him back repressed memories to which he himself had no access, except with outside help. Disguised as Gradiva Zoe was able to give Hanold back his lost memories.

In the History of the Psychoanalytical Movement Freud wrote: “the theory of repression is the corner-stone on which the whole structure of psychoanalysis rests.” In psychoanalytic treatment the repressed is brought to consciousness. The essence of this change is the awakening of lost feelings. “Psychoanalytic treatment is an attempt at liberating repressed love which has found a meagre outlet in the compromise of a symptom.”

In his study of Gradiva Freud found a way of illustrating his ideas in terms of a work of literature. Art and science converged. Psychoanalysis was revealed as a science of love.