Pankejeff's anxiety lasted for six months after the dream.

It finally ended when his mother began reading him the bible. He took an interest in the story of Jesus (with whom he shared a birthday), and was particularly curious about the father-son relationship between Jesus and God.

This gave rise to a period of religious obsession. He performed all sorts of elaborate prayer rituals, such as kissing the religious icons in the house and crossing himself before going to bed. This relieved his anxiety, but it was also a time of internal conflict: he struggled against intrusive thoughts that he considered blasphemous.

It wasn’t until much later, after the deaths of his father and sister, that he began to suffer from depression and consulted with Freud.

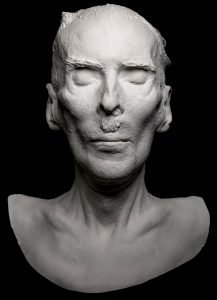

Death Mask of the Wolf Man

His later life was not a happy one.

Shortly after his treatment with Freud ended, the Bolshevik Revolution broke out in Russia. As a wealthy aristocrat, he had all his belongings and fortune confiscated and was forced to leave the country.

He and his wife settled in Vienna, where he spent the rest of his life. He was penniless, and often dependent on financial support from Freud and his colleagues.

Pankejeff struggled with psychological difficulties throughout his life. In 1926 he went into analysis once again, this time with another psychoanalyst, Ruth Mack Brunswick.

A keen painter, Pankejeff sold artworks to get by. He mostly painted still lifes and landscapes, but also painted several versions of his famous dream.

Over the years, Pankejeff became something of a celebrity in psychoanalytic circles and was interviewed several times. He was dismissive of Freud’s construction of his ‘primal scene’, but spoke extremely highly of him.

He also found some stability in his identity as a one of Freud’s celebrated patients. In later life he signed his letters and paintings with the name ‘Wolf Man’.

Discover more:

Related resource

The Interpretation of Dreams

A guide to Sigmund Freud's theory of dreams and his method of dream interpretation.