What about dreams that don’t make sense?

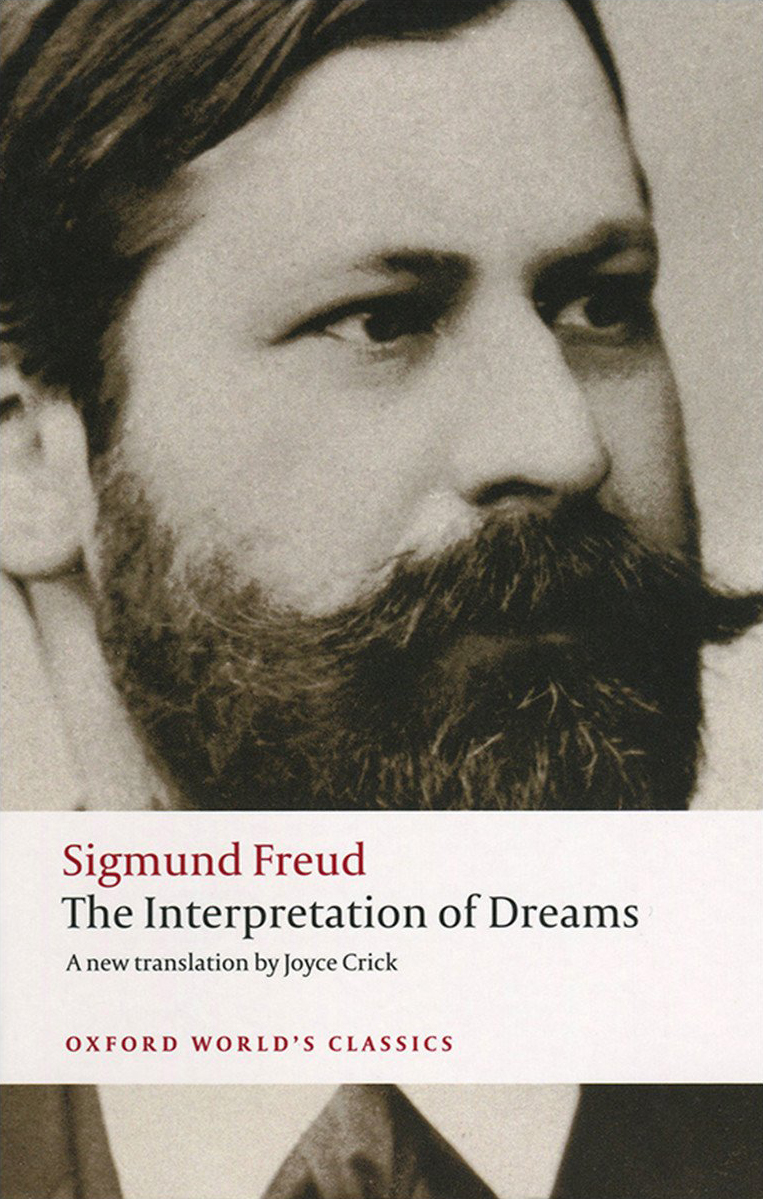

Freud’s next step is that a dream is the disguised fulfilment of a repressed wish.

The claim that dreams fulfil wishes is easy to criticise at a glance:

- What about dreams where things go wrong?

- What about dreams that don’t makes sense?

- What about nightmares?

Freud’s response is: dreams should not be taken at face value!

It is at the level of the thoughts behind dreams that wish fulfilments can be found.

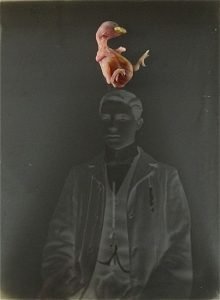

Freud makes a crucial distinction between two levels of the dream:

- The manifest content (the dream as we remember it)

- The latent content (the underlying ‘dream thoughts’ that make up the dream)

The wishes expressed in dreams are found at the level of the latent content, which can be brought out through free association.

They are represented in the manifest content, but in a disguised form.

In Freud’s words:

“My theory is not based on a consideration of the manifest content of dreams, but refers to the thoughts which are shown by the work of interpretation to lie behind dreams.”

-

Example

-

A woman tells her analyst: “I dreamt of an owl flying through a lego door.”

The analyst recognises that this is the manifest content of the dream. He asks the patient: “what do you think about owls?”

The patient makes the following associations:

- I was watching a nature documentary last night.

- There was a bit where an owl catches a mouse, but the mouse gets away.

- I thought owls were supposed to be wise.

- My father was a wise man.

- I adored him for it.

- My mother didn’t.

- But she kept coming back to him.

- God I hated her for it.

- She wouldn’t let go.

These associations make up some of the latent content of the dream.

Freud argued that wishes are concealed at this level. Can you see any?

Censorship

If the latent wish has been disguised, Freud argues there must be something in the mind defending against the wish, working to stop it from entering the manifest content where we would become conscious of it.

Dreams of the death of a loved one, or of unacceptable sexual desires, show clearly the existence of wishes which are normally repressed.

The wish has in some way been ‘forbidden’ from consciousness and remains in a state of repression.

We saw earlier that a wish involves a prohibition. Freud now adds that prohibitions don’t always come from the outside world: there must be internal prohibitions in the mind itself.

Freud calls these internal prohibitions censorship, and he likens it it to the censorship of letters, political newspapers and works of art. “The stricter the censorship,” he argues, “the more extensive will be the disguise.”

This gives us a picture of two opposing forces in the mind:

- One that constructs the dream wish

- One that censors the dream wish

In order to appear in the dream, the dream-wish must undergo distortion to get past the censorship. The dream is produced as a kind of compromise between these two forces.

Freud’s conclusion is: the mind is in conflict with itself!

Discover more:

Next chapter

The Dream-Work

Dreams follow their own kind of logic that Freud calls the 'dream-work'.