Hampstead Child Therapy Courses

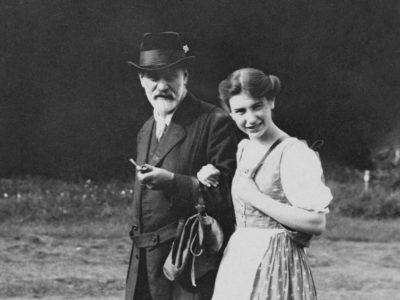

In 1947, Anna Freud and Kate Friedlander established the Hampstead Child Therapy Courses, and a children’s clinic was added five years later.

Now that she was training English and American child therapists, her influence in the field grew rapidly. One of her staff wrote:

“The Hampstead Clinic is sometimes spoken of as Anna Freud’s extended family, and that is how it often felt, with all the ambivalence such a statement implies.”

At the clinic, Anna and her staff held highly acclaimed weekly case study sessions which provided practical and theoretical insights into their work.

Developmental lines

Their technique involved the use of developmental lines charting theoretical normal growth “from dependency to emotional self-reliance”, and diagnostic profiles that enabled the analyst to separate and identify the case specific factors that deviated from, or conformed to, normal development.

In her book Normality and Pathology in Childhood (1965), she summarised material from work at the Hampstead Clinic as well as observations at the Well Baby Clinic, the Nursery School and Nursery School for Blind Children, the Mother and Toddler Group and the War Nurseries. In child analyses, Anna felt that it was above all transference symptoms that offered the “royal road to the unconscious.”

Anna’s work in the United States

From the 1950s until the end of her life Anna Freud travelled regularly to the United States to lecture, teach and visit friends. During the 1970s she was concerned with the the problems of working with emotionally deprived and socially disadvantaged children, and she studied deviations and delays in development.

At Yale Law School she taught seminars on crime and the family: this led to a transatlantic collaboration with Joseph Goldstein and Albert Solnit on children and the law, published as Beyond the Best Interests of the Child (1973).

She also began receiving a long series of honorary doctorates, starting in 1950 with Clark University (where her father had lectured in 1909) in 1950 and ending with Harvard in 1980.

Like her father, she regarded awards less in a personal light than as honours for psychoanalysis, though she accepted the praise with good grace and characteristic humour – the speeches about her achievements made her feel as if she were already dead, she commented.

She died peacefully in London on 9 October, 1982.

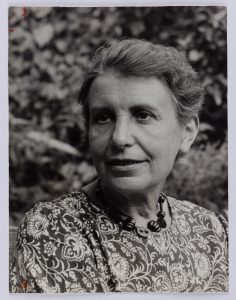

Anna Freud’s legacy

The publication of her collected works was begun in 1968, the last of the eight volumes appeared in 1983, a year after her death.

In a memorial issue of The International Journal of Psycho-Analysis collaborators at the Hampstead Clinic paid tribute to her as a passionate and inspirational teacher, and the clinic was renamed the Anna Freud Centre. In 1986, her home for forty years was, as she had wished, transformed into the Freud Museum.

Anna Freud’s work continued her father’s intellectual adventure. She said:

“We felt that we were the first who had been given a key to the understanding of human behaviour and its aberrations as being determined not by overt factors but by the pressure of instinctual forces emanating from the unconscious mind…”

Her life was also a constant search for useful social applications of psychoanalysis, above all in treating, and learning from, children.

“I don’t think I’d be a good subject for biography, not enough ‘action’! You would say all there is to say in a few sentences – she spent her life with children!”

Discover more: