“When I was seventeen I had run up a largish account at the bookseller’s and had nothing to meet it with; and my father had scarcely taken it as an excuse that my inclinations might have chose a worse outlet.”Sigmund Freud

When Freud prepared to leave his home in Vienna for London in 1938 it was unclear if he would be able to take his library.

He and his daughter Anna assessed it book by book. Almost one-third was taken out and given to a local book dealer.

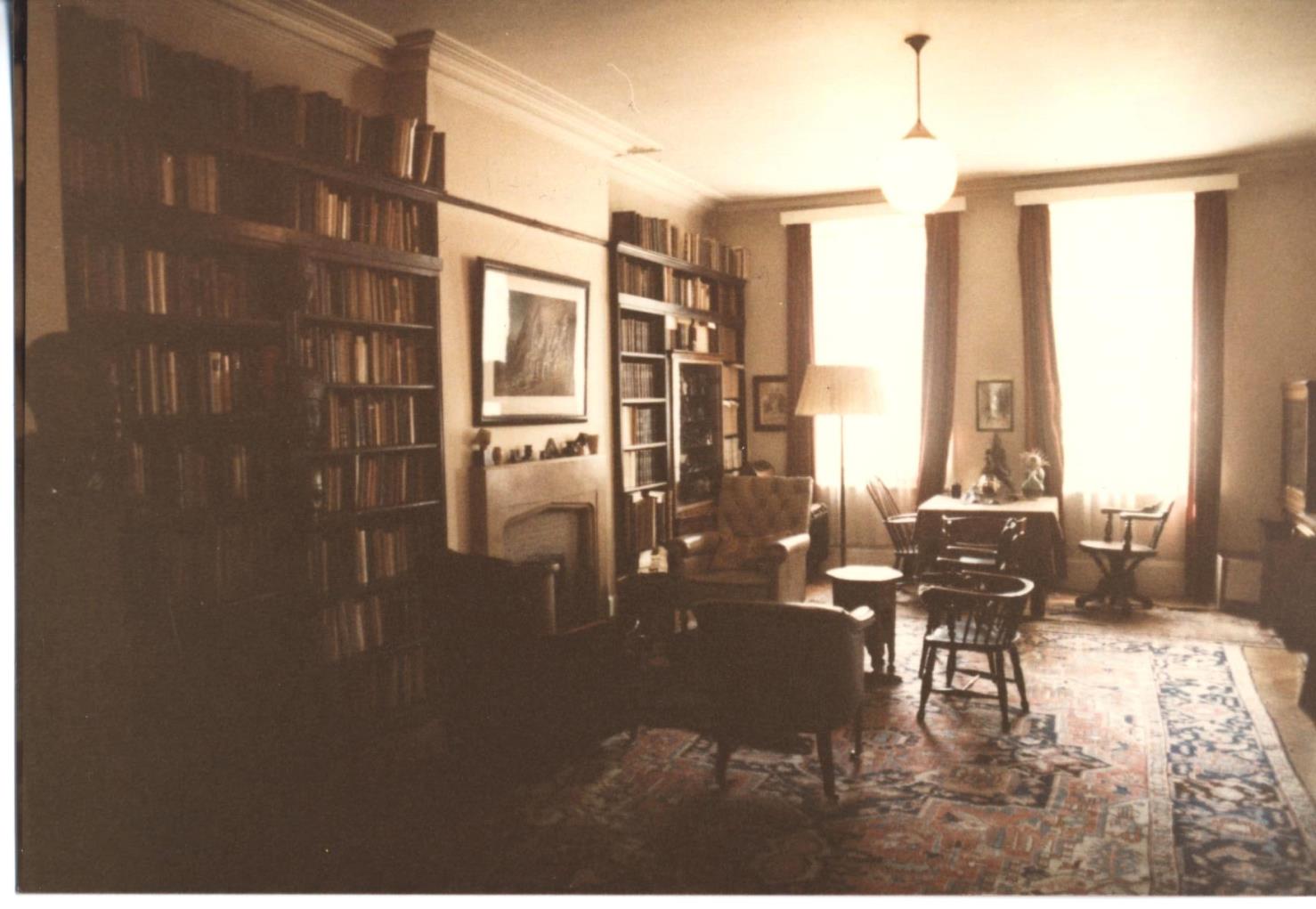

The rest Freud was finally able to take to London. This was largely due to help from Marie Bonaparte, who assisted the family in their escape. They were placed where they sit today: the shelves of the study in 20 Maresfield Gardens, London.

Freud had loved books from an early age.

In 1868, aged 12, he won a prize at school in the form of a book: Friedrich von Tschudi’s Animal Life of the Alps. He was bored by many of the texts in his his school’s library, though ambitious in his own reading. He tackled T.H. Buckle’s The History of Civilization in England as a teenager.

Just as Freud loved collecting antiquities, he had a passion for acquiring books.

He received them as gifts from friends and family, and gave them as gifts to loved ones. In the 1880s, while studying medicine, his library steadily began to grow.

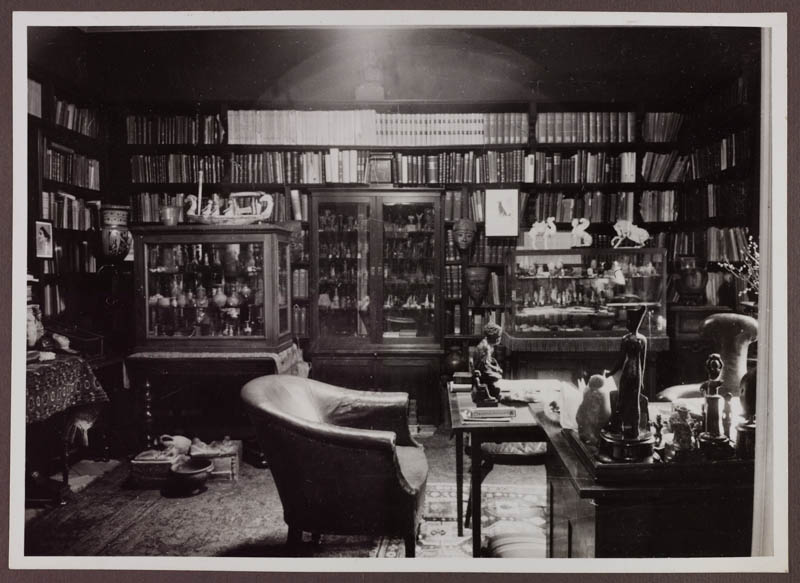

When Freud and his wife Martha moved to Berggasse 19, Vienna, his library grew more. He continued to collect books and, as his own works were published, he was sent more as gifts.

Freud’s own works were not displayed openly on his shelves. Instead he arranged works by mentors, students and peers in the world of psychoanalysis, neurology and medicine.

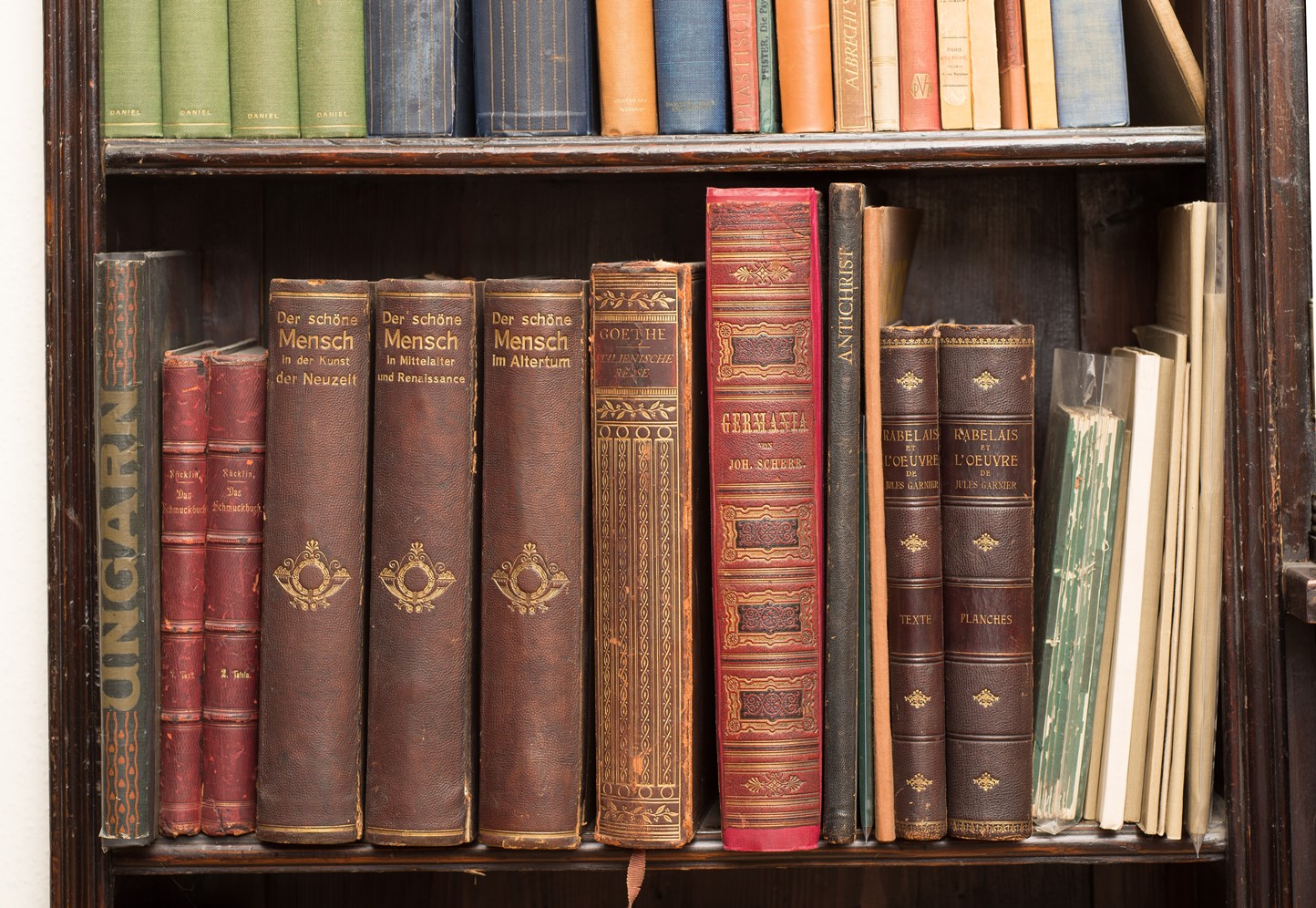

But Freud’s library also stretched far beyond his professional life. Works of literature, by Shakespeare, Goethe and Schiller, lined walls, with books on ancient history, archaeology and religion also accumulating. In later years, Freud said he bought books faster than he could read them.

During his student days, however, Freud often used public libraries to sate his appetite for books when money was in short supply. Writing to his friend Eduard Silberstein he says “I am gradually making up for my lack of knowledge of modern literature through our Union Library”, referring to the Reading Room and Lecture Hall of Jewish Students.

This may explain why a number of books known to be loved by Freud are not in his library. Freud wrote about other writers and books not only in his own published works, but also in letters to friends and colleagues. It’s possible, therefore, to know what he had read even if the books themselves weren’t in his personal library.

When Freud and his daughter Anna finally packed up his library in Berggasse 19 in the spring of 1938, its fate was unknown.

The Nazis would have deemed many of the books to be at odds with their ideology, and were holding book burning ceremonies.

But when the books, along with his collection of antiquities, arrived unscathed in London weeks later, the library was eventually re-assembled.

The double room on the ground floor of 20 Maresfield Gardens was to be Freud’s study and library, laid out in much the same way as his consulting room in Vienna. Books were placed on the shelves, mostly in categories but not following any formal system. Freud was once again surrounded by his favourite food: books.