Many of the books read and loved by Freud are nowhere to be found in his library.

As a student, Freud visited public libraries. He wrote to his friend Eduard Silberstein:

“I am gradually making up for my lack of knowledge of modern literature through our Union library.”

Freud was an admirer of the great figures in literary history, and his library shows this. The Complete Works of both Shakespeare and Goethe line his walls. He admired Homer and Sophocles, as his collection of ancient Greek and Roman antiquities might imply.

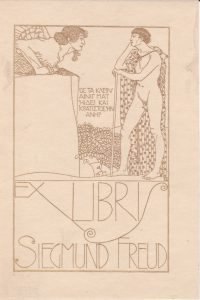

Freud’s ex-libris bookplate

Freud had his own ex-libris (a decorative label indicating a book’s owner). Designed in a typical Jugendstil (Art Nouveau) style, it was made in 1904 by the artist Bertold Löffler.

It shows Oedipus and the Sphinx with the famous inscription in Greek: “Who solved the riddle and was a mighty man.”

It is not known why his name is misspelled as Siegmund, though this may be the reason it is stuck in only 16 of his books.

Among the books with the ex-libris inside are Freud’s collection of Schliemann.

Heinrich Schliemann was a 19th century pioneer in the field of archaeology. His published reports on Mycenae and Tiryns chronicled his discoveries at the ruins of the two greatest cities of the Mycenaean civilization, which dominated the eastern Mediterranean world from the 15th to the 12th century B.C.

These books were cherished by Freud and were inscribed by him with the date of their purchase in the 1890s.

Freud’s copy of Wilhelm Jensen’s Gradiva was another of his most cherished books.

Freud’s copy of Wilhelm Jensen’s Gradiva was another of his most cherished books.

In 1907 Freud was alone on holiday in Rome. On 24th September he wrote home:

“Imagine my joy when after such long solitude I saw a dear, familiar face today in the Vatican; however the recognition was one-sided, for it was the Gradiva, high up on a wall.”

Afterwards Freud acquired a cast of the bas-relief in the Vatican to hang in his consulting room.

Jean-Martin Charcot, Freud’s early teacher and mentor, is also present in his consulting room.

A print of Une leçon clinique du Dr. Charcot à la Salpêtrière by E. Pirodon, after the 1887 oil painting by Andre Brouillet, hangs above Freud’s famous consulting couch.

Charcot’s writings are well represented in his library as well. Volumes of Leçons du mardi à la Salpêtrière, in their original French, sit alongside Freud’s own German translations of Neue Vorlesungen über die Krankheiten des Nervensystems, complete with his own preface and footnotes.

Freud continued to amass works by mentors, colleagues and, eventually, students of his own.

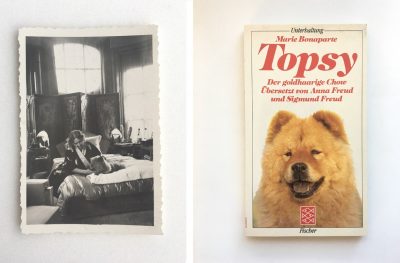

One such student turned colleague, analysand and friend was Marie Bonaparte, Princess of Greece. Bonaparte was a friend of both Sigmund and Anna Freud, and was hugely influential in getting the family, their possessions and Freud’s library out of Austria after the Nazi invasion of 1938.

Like Freud, Marie Bonaparte was a dog lover. Topsy, her beloved Chow, was the subject of her 1937 book Topsy: the Golden-Haired Chow.

The following year, hoping to distract themselves from the tense and frightening political situation of 1938 Austria, Sigmund and Anna Freud embarked (no pun intended) on a German translation of their friend’s book.

Bonaparte dedicated her own copy:

“To Professor Freud, who understands men and loves beasts.”

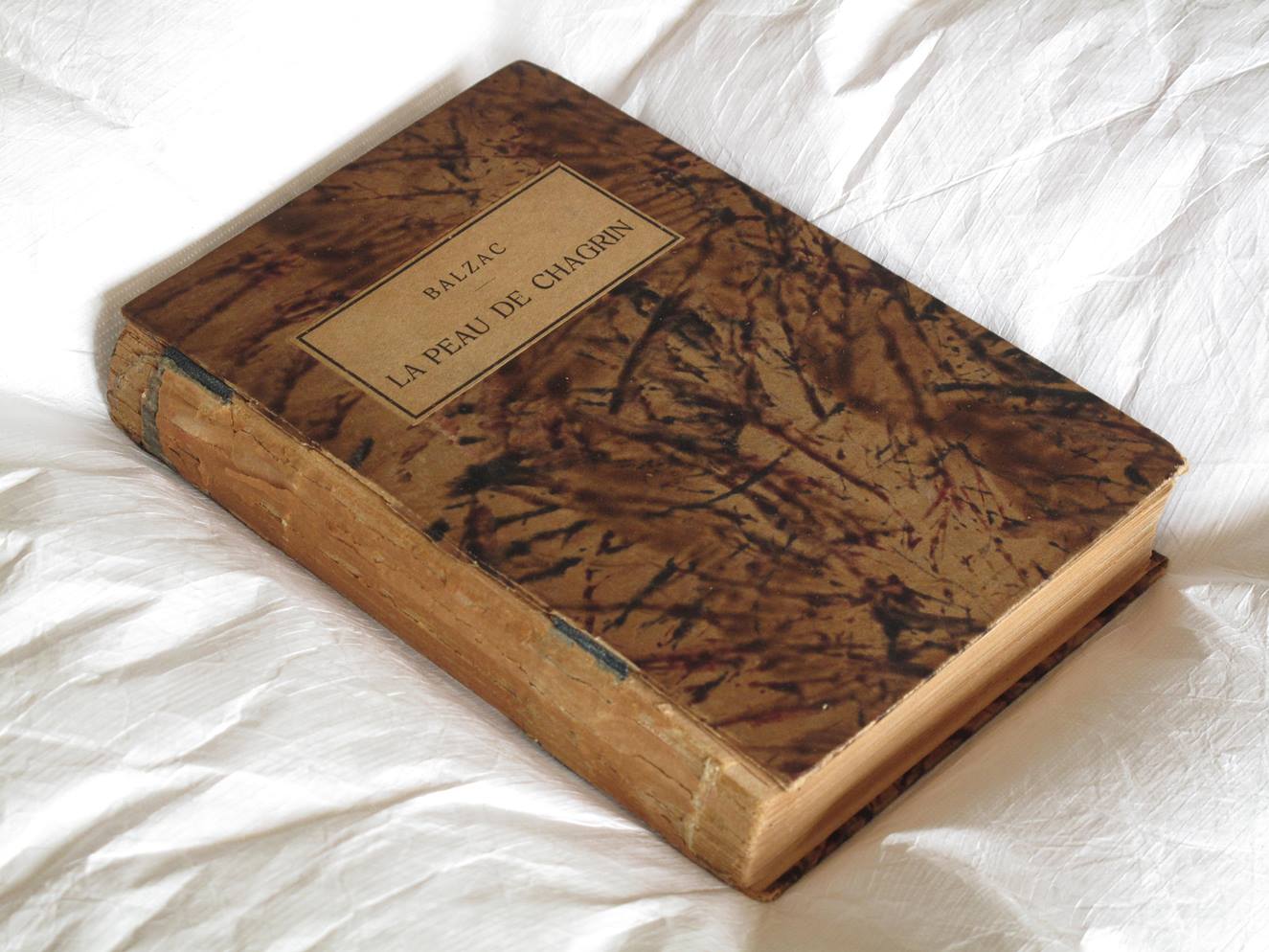

The last book Freud read

When Freud died in September 1939, the book by his bedside was Balzac’s La Peau de chagrin. This was the last book Freud read.