Princess Alexandra and Karen Booth

Back in 1856, the young Sigismund Freud, son of a relatively impoverished father, grew up in a very small, rented room on the upper floor of the rather modest home of a locksmith, in the outskirts of the Austrian empire.

Only a man of Freud’s genius and perseverance could have extricated himself from such humble foundations and then risen to such great fame and influence, so much so that he eventually became known personally to many members of various European royal families.

Indeed, as early as 1902, shortly before his forty-sixth birthday, Freud received an audience with none other than Austria’s emperor and Hungary’s king, the illustrious seventy-one-year-old Kaiser Franz Josef, who confirmed the young Jewish doctor’s professorship at Vienna’s sole university, the Universität zu Wien – quite an achievement during those overtly anti-Semitic times.

Nowadays, in the United Kingdom, we refer to the family of Queen Elizabeth II as the “Royal Family”, but, back in 1902, the newly-christened Professor Freud would have had to address the Austro-Hungarian Kaiser as “His Imperial and Royal Apostolic Majesty” – known in the German language as the “Kaiserliche und Königliche Apostolische Majestät”. After all, the Kaiser served as head of state of the sprawling Austrian empire, which, in Freud’s day, included not only Austria and Hungary but, also, Bohemia, Croatia, Dalmatia, Galicia, Illyria, Moravia, Slavonia and, even, parts of Italy. Thus, few could have received an honour greater than a visit to Franz Josef.

Princesse Bonaparte

As Freud’s reputation grew, his royal connections became more intimate, especially after the French-born princess, Marie Bonaparte, the great-grandniece of the legendary Napoléon Bonaparte, arrived in Vienna to undergo psychoanalytical treatment on Freud’s famous couch in his consulting room at Berggasse 19 – the very same couch now lovingly preserved in the iconic study at 20, Maresfield Gardens, the home of the Freud Museum London.

The Princesse Bonaparte could not only trace her lineage quite easily to the former French emperor, but, moreover, she enhanced her own royal credentials when she married a Grecian-Danish prince, George, son of the one-time king of the Hellenes, nephew to the king of Denmark, and cousin to the Russian tsar. And over the course of time, Marie Bonaparte sent a number of her royal relatives to Freud for clinical appointments.

Freud’s relationship to the British Royal Family began, during the 1920s, when he offered consultative recommendations to the psychiatrist and psychoanalyst Dr. Ernst Simmel, who treated the emotionally troubled Princess Alice of Greece and Denmark – a great-granddaughter of Queen Victoria and, also, the wife of Marie Bonaparte’s nephew, Prince Andrew, who had recently become the parents of a young child, Philip, who, in 1947, would eventually marry Her Royal Highness The Princess Elizabeth, the future monarch of Great Britain. Thus, Sigmund Freud had offered expert clinical advice about the woman who would, in due course, serve as mother-in-law to our very own Queen.

Marie Bonaparte occupied an increasingly vital role in the life of Sigmund Freud and his family, not only as a source of royal referrals but, more impactfully, as one of the leading founders of the psychoanalytical movement in France and beyond. Moreover, in 1938, the Princesse became a truly significant campaigner against the Nazis, and drew upon her wealth and influence in order to help Freud and many of the members of his family to escape from Adolf Hitler’s Vienna.

After Freud’s death, the Princesse Bonaparte continued to promote psychoanalysis in many a Royal setting and often dined with her nephew, Prince Philip, and with his wife. For instance, in 1953, while attending the Coronation of Elizabeth II – Bonaparte’s niece by marriage – the Princesse stood next to none other than François Mitterrand (who had just become elected as the Ministère de l’Europe et des Affaires étrangères) and, according to the reminiscences of Bonaparte’s nephew, Prince Michel of Greece and Denmark, she even offered to psychoanalyse the future leader of France!

Anna Freud C.B.E.

Anna Freud, daughter of the founder of modern psychology, and a brilliant progenitor of psychoanalysis in her own right, could also boast about royal experiences, having enjoyed a long and supportive friendship with Marie Bonaparte. Moreover, as a young woman in Vienna, Fräulein Freud had once attended a Jause – an Austrian high tea – with the former daughter-in-law of the Kaiser, the princess Stéphanie. And many years later, in 1967, Anna Freud, who had, by that point, lived in London for nearly thirty years, eventually received a C.B.E. award – Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire – from Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, in the Civil Division of the New Year Honours List. A framed certificate signed by both the Queen and Prince Philip hangs in the Freud Museum London to this very day.

Although Sigmund Freud died in 1939 and his professional heir Anna Freud passed away in 1982, the Royal Family of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland has continued to honour these extraordinary Viennese refugees in various fashions.

Her Royal Highness Princess Alexandra

Perhaps of greatest significance, in 1986, Her Royal Highness Princess Alexandra, The Honourable Mrs. Angus Ogilvy – first cousin to Queen Elizabeth II – kindly accepted an invitation from the soon-to-be-launched Freud Museum – the former London home of Sigmund Freud and Anna Freud – and had generously agreed to unveil a plaque at the impending opening ceremony.

Why did the Freud Museum approach Princess Alexandra rather than some other member of the British Royal Family?

One must appreciate that although nowadays so many British Royals have embraced mental health in such a public way, not least Prince William and Prince Harry, grandsons to Her Majesty, back in the 1980s, very few people spoke openly about psychological wellbeing and many still regarded psychoanalysis and psychotherapy as rather bizarre procedures designed only for extremely mentally ill people.

Princess Alexandra, Dr Harold Blum and Lord Goodman

Fortunately, Princess Alexandra had grown up in a very particular branch of the Royal Family which had long engaged with psychoanalysis, more seriously perhaps than any other members of the Windsor clan. It will not be widely appreciated that, in 1934, her father, Prince George, the Duke of Kent – son of King George V and Queen Mary – became the very first President of London’s Institute of Medical Psychology, the governing body of the Tavistock Clinic, an organisation that pioneered the development of the psychological therapies for members of the general public who could not afford private fees. After his tragic death in a wartime plane crash in 1942, his widow, Princess Marina, the Duchess of Kent (niece of Marie Bonaparte), assumed this key stately role at the Tavistock Clinic. And, upon her death in 1968, the daughter, Princess Alexandra (great-niece of Marie Bonaparte), continued the legacy of her parents, encouraging the work of that long-standing, now century-old psychotherapeutic institution.

Thus, in view of the admiration of Princess Alexandra’s parents for mental health professionals, and as a result of her lengthy family history with the Tavistock Clinic, she seemed the obvious first choice among all the members of the Royal Family to serve as a champion of the museum.

Museum Launch

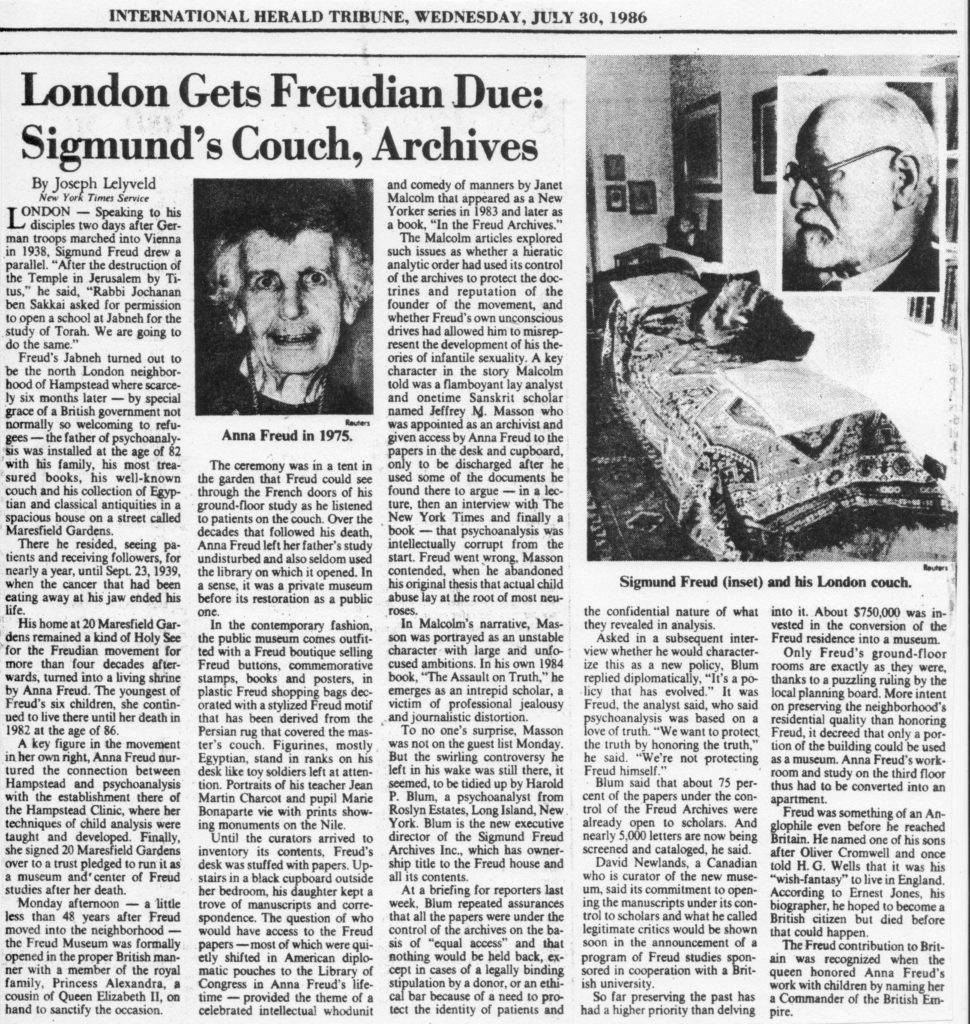

In the mid-afternoon of Monday, 28th July, 1986, a limousine arrived at 20, Maresfield Gardens, surrounded by cordons of police, and out stepped Her Royal Highness, beautifully dressed in a cream-coloured suit with a large hat, accompanied by her lady-in-waiting, Lady Angela Whiteley. After receiving a special private tour of the museum, the Princess entered the back garden of Freud’s home, crowded with members of the Freud family as well as noted psychoanalysts from all over the world, and then, at precisely 3.32 p.m., Her Royal Highness pulled a cord unveiling a commemorative plaque, thus officially launching the museum.

After the formal ceremony concluded, Professor Albert Solnit, an American psychoanalyst who had worked closely with Anna Freud, escorted the Princess round the garden and introduced her to members of the Freud dynasty, including the elderly Lucie Freud, the widow of Sigmund Freud’s youngest son, Ernst L. Freud. Not long thereafter, the museum’s inaugural curator, David Newlands, accompanied the Princess back into the house whereupon she signed the visitor’s book and received a special posy as a token expression of thanks before stepping back into her limousine with her lady-in-waiting.

Historic Day

Though merely a youngster at that time, on the verge of assuming a post at the newly-created Freud Museum, I had the great honour of attending that memorable opening ceremony, which I remember with tremendous fondness and affection. I still recall the way in which each of the members of the Freud family had to bow or curtsy when introduced to the Princess in a special queue.

Since that historic day, the Freud Museum (now restyled as Freud Museum London) has become an increasingly impressive cultural icon, and its remarkable staff team has worked tirelessly to educate the world’s population about the extraordinary contributions of Sigmund Freud, Anna Freud, and the generations of psychoanalytical mental health professionals who have followed in their footsteps. The Freud Museum owes deepest thanks to Princess Alexandra for her public support of this important project.

Thus, in spite of his humble beginnings in the outer recesses of the Austrian empire, Sigmund Freud ultimately developed important links with global royalty. But let us not forget that, within the healthcare community, Sigmund Freud ultimately became the veritable emperor of mental health in his own right, and he remains so, quite deservedly, to this very day.

Scholarly Note:

Throughout this essay, the author refers to the father of psychoanalysis by both his birth name, “Sigismund Freud” and, also, by his adult name, “Sigmund Freud”. Likewise, the author describes the French aristocrat Marie Bonaparte as a “Princesse”, whereas he uses the more traditional English spelling of “Princess” when referring to the Queen’s cousin, Princess Alexandra.

Professor Brett Kahr

has worked in the mental health profession for over forty years. During this time, he has enjoyed a long and enriching relationship with the museum, having served as Deputy Director of the International Campaign for the Freud Museum back in 1986-1987 and, subsequently, as Trustee for three terms of office, between 2009-2020. More recently, he has had the privilege of becoming the Honorary Director of Research at Freud Museum London. On 16th September, 2021, Kahr’s newest book, Freud’s Pandemics: Surviving Global War, Spanish Flu, and the Nazis, will be released as the inaugural title in the new “Freud Museum London Series”, published by Karnac Books. This book, based upon Kahr’s fundraising talk for the museum, “How Freud Survived the Coronavirus of His Time: Lessons from a Beacon of Survival”, is available as an on-line resource.