Sigmund Freud, 1920 © Freud Museum London

In March, 2020, the deadly coronavirus pandemic erupted on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean and changed our world immeasurably, causing huge disruption and terror and bereavement.

As the infection rate of this shockingly lethal disease has risen with alarming rapidity, each one of us had to readjust our lives, both personally and professionally, in a desperate effort to ensure our physical safety and our psychological health.

After the outbreak of COVID-19, virtually every single mental health professional, myself included, had to alter the very physicality of our daily clinical work. In more normal times, those of us who practise psychoanalysis and psychotherapy would welcome our patients into a quiet, cosy consulting room and invite these men and women and children to sit in a comfy chair or, even, to recline upon the Freudian couch, perched only inches away from our own seat. But once the coronavirus began to spread, each of us had to transform our practices from such in-person intimacy to a more remote method of mental health care.

As someone who has never particularly embraced modern technology, I elected to communicate with my patients on the old-fashioned landline telephone, rather than via the computer. I have found this to be a surprisingly effective means of persevering with psychological treatment. The telephone has provided me and my patients with an effective method of engaging in rich, private conversations, and, in consequence, we now listen to one another on the landline with a laser-like intensity.

‘Zoom psychoanalysis’

My more technologically sophisticated colleagues, by contrast, transferred their practices immediately to a laptop and became pioneers of ‘Zoom psychotherapy’ and ‘Zoom psychoanalysis’. Many patients did agree to this new method of online therapeutic work, but many others dropped out of treatment, too exhausted by Zoom fatigue. Many of my fellow colleagues, even the younger ones, complained that by staring at the screen all day, they had begun to experience unbearable pains and strains in their eyes. Nevertheless, the vast majority of clinicians have found a way to meet their patients regularly and reliably online.

Sigmund Freud, the father of modern psychoanalysis and psychotherapy, died in 1939, long before the invention of the computer and the internet. If he had lived and worked today, I cannot imagine how he would have responded to the sheer fact that his creation of the intimate psychoanalytical conversation has become Zoomified in this way across the planet. Freud might have had to shrug his shoulders and lament that, in the wake of a pandemic, practitioners simply had no other option. But he might also have expressed great sadness that the extremely private and confidential conversations that he had helped to facilitate must now be practised with the assistance of such complicated electrical devices.

It may not be widely appreciated that Sigmund Freud had little affection for the technological developments of his time. According to his eldest son, Martin Freud (1957), the father of psychoanalysis did not particularly like the telephone or the typewriter or the radio, or, even, the bicycle. Thus, had he lived through COVID-19, he might have struggled to adjust to a Zoom platform.

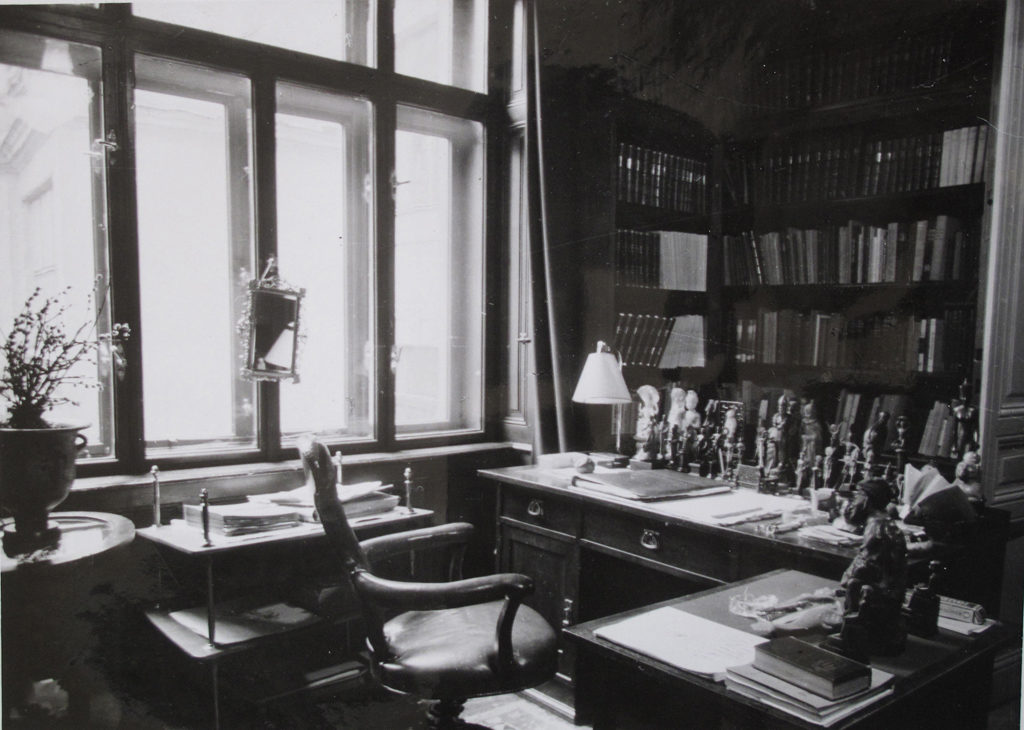

Sigmund Freud’s study in Berggasse 19, Vienna, 1938 © Freud Museum London

Global Catastrophe

But Freud did have to battle through the Weltkrieg – otherwise known as the Great War – and this global catastrophe affected his clinical practice hugely. Many of his patients could no longer afford psychoanalytical treatment, and many had to enlist in the armed services and could not, therefore, attend sessions with Freud on a daily basis. Hence, in the wake of the First World War, Freud and his family suffered financially. And then, just as the war began to end, after more than four years of fighting, the deadly “Spanish flu” blighted our planet in 1918, 1919, and 1920, and devastated many families, claiming somewhere between 50,000,000 and 100,000,000 lives, and, perhaps, even more (e.g., Barry, 2004; Arnold, 2018). In view of these losses, many people struggled simply to stay alive, and few had the energy or the resources to pursue a lengthy, multi-frequency psychoanalysis.

Thus, in the wake of the war and the Spanish flu, Sigmund Freud knew that he would have to transform the very nature of his working life.

And he did so, not by installing Zoom, but, rather, by taking English lessons!

Psychoanalysis in English

By the end of 1918, the world war and the viral pandemic had crushed the Austrian economy almost completely, and few, if any, Viennese could afford Freud’s clinical services. He sensed, and rightly so, that he would have to reconfigure the discipline of psychoanalysis from an exclusively German-language process with local patients to a more international practice for wealthy patients from Great Britain and from the United States of America.

At that time, psychoanalysis had become increasingly well known in English-speaking countries. And both of these Allied nations, winners of the war, had access to far greater monetary resources. Hence, British and American physicians began to write to Freud asking whether they might come to Vienna to train with him and to undergo a short period of psychoanalysis on his famous couch. Freud had no wish to turn down paid work; moreover, he strongly hoped to disseminate his important psychological discoveries worldwide, and thus, he knew that he would have to begin to practise the craft of psychoanalysis in English.

As a deeply well-educated man, steeped in the classics, and quite fluent in a range of foreign languages, Sigmund Freud already enjoyed a facility not only in German, his native language, but, also, in French and Italian and Spanish, and, also in the ancient languages of Greek and Latin. Moreover, he had already developed a considerable knowledge of English as well, not least in view of the fact that his two elder half-brothers had relocated to Manchester and had offered the young Freud opportunities to visit (Jones, 1953). But, although he could read medical literature in English, he had not spent much time treating native English-speaking patients.

Thus, in 1919, Sigmund Freud (1919b) actually engaged an English teacher in order to spruce up his linguistic skills.

Expanding Post-war Practice

Fortunately, he did, indeed, begin to attract foreigners – former “enemies”, in fact, from Allied countries – such as Dr. David Forsyth, a British physician who specialised in children’s medicine, and who came to the Berggasse to undergo a training analysis (Jones, 1919; Freud, 1919c, 1933; cf. Roazen, 2000).

Freud offered Forsyth an English-language psychoanalysis, and, in due course, this became increasingly common among Viennese clinicians, eager to expand their flagging, post-war practices (e.g., Menaker, 1989). The father of psychoanalysis experienced so much gratitude towards Forsyth that, after the arrival of this new patient, Freud instructed Frau Beata Rank, the wife of the psychoanalyst Dr. Otto Rank, to host a special dinner party in Forsyth’s honour (Roazen, 2000; cf. Roazen, 1990).

We know from Freud’s patient calendar (i.e., his clinical appointments diary) that Forsyth commenced treatment on Monday, 6th October, 1919, and attended for six sessions weekly – Mondays through Saturdays inclusive – until Tuesday, 18th November, 1919. In total, he participated in thirty-eight psychoanalytical sessions – a relatively short experience by contemporary standards but by no means unusual at that period of time, especially for foreigners who wished to acquire a taste of Freud (May, 2006, 2007a, 2007b).

Forsyth repaid Freud’s kindness and attention with gratitude. Upon his eventual return to London, he became not only a progenitor of psychoanalytically orientated paediatrics, as well as a key early member of the British Psycho-Analytical Society, but, moreover, the author of a very loyal textbook, The Technique of Psycho-Analysis (Forsyth, 1922), as well as an insightful paper on the use of Freudian methods in the understanding of paranoid dementia, published in the prestigious Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine (Forsyth, 1920).

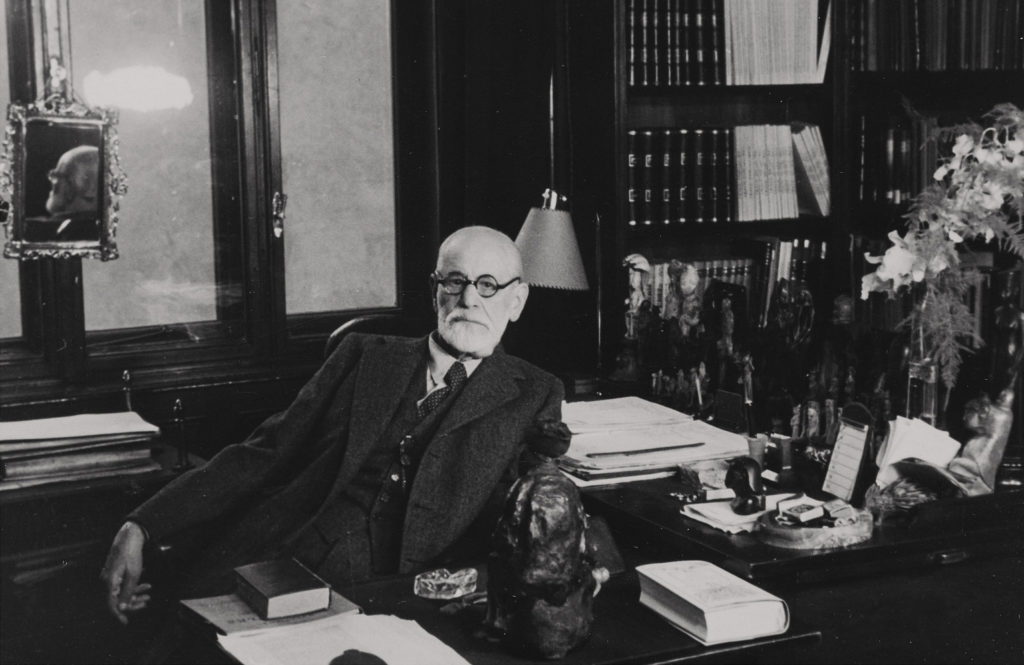

Sigmund Freud in his study in Berggasse 19, Vienna, 1938 © Freud Museum London

‘The first window opening in our cage.’

Undertaking regular, foreign-language psychoanalysis proved a most wise strategy because, by October, 1920, fully five of Freud’s nine patients had come to him from English-speaking countries (Freud, 1920), and many more would follow in due course (e.g., Stern, 1922; Grinker, 1940; Wortis, 1940, 1954; H.D. [Hilda Doolittle], 1945a, 1945b, 1945c, 1945d, 1946, 1956; Eissler, 1952, 1953; Oberndorf, 1953, 1958; Blanton, 1971; Dorsey, 1976; Kardiner, 1977; Burlingham, 1989; Cameron and Forrester, 1999; Forrester and Cameron, 2017). With deep relief, Freud (1919a, p. 340) could at last begin to see what he described as “The first window opening in our cage.”

In fact, after a time, Freud had welcomed so many British and American patients into his practice that he often had to no free spaces at all and had to refer keen individuals to his more junior colleagues. When the young London-born Mr. Lionel Penrose, a budding geneticist, physician, and psychoanalytical enthusiast (and, in years to come, the father of the future Nobel Laureate, Professor Sir Roger Penrose), requested treatment from the father of psychoanalysis, Freud had to refuse as he simply had no vacancies and, consequently, he referred Penrose to his talented colleague, Dr. Siegfried Bernfeld (Roazen, 2000).

Honorary Englishman

Thus, although Freud had crafted psychoanalysis in his native German language, he succeeded in reframing his daily working life to become an honorary Englishman of sorts, thus filling his practice successfully and managing to support his family. In this way, he transformed his clinical work, much as my colleagues and I have endeavoured to do nowadays by transferring our practices to the telephone or the laptop, with many of us having had to become overnight experts in ‘Zoom psychoanalysis’.

Freud undertook the reconfiguration of his German work into English in large measure to feed his family, but his Anglicisation of psychoanalysis produced very positive side effects. Two of his patients, Mr. James Strachey, a Briton, and Mrs. Alix Strachey, his American-born wife, became Freud’s two most prominent translators, without whom we would never have had the privilege of enjoying the twenty-four volume collection of Freud’s writings, The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, published between 1953 and 1974.

Furthermore, Freud had little sense that, in 1938, he and his family would have to emigrate from Austria to England in order to escape the Nazi menace. Thus, one might argue that his English lessons of 1919 might well have proved indispensable on such numerous different fronts.

Remote Therapy

Many colleagues and I have had to make a complicated adjustment to our long-established practices, and, moreover, so have our patients. Fortunately, most of us seem to be managing with remote therapy in this ongoing pandemic world. In fact, now that patients need no longer attend the consulting room in person, several of my colleagues have even received referrals from patients who live overseas! In the olden days, if one wished to consult a psychotherapist in London, one actually had to live in the United Kingdom, but, nowadays, with the availability of Zoom and the telephone, the possibilities may well become limitless.

Let us hope that with the ongoing survival and, moreover, expansion of psychoanalytical work across the world that those of us who continue to honour and practise Freud’s legacy might be able to make a contribution to the improvement of everyone’s mental health amid this tragically ugly chapter in world history.

Professor Brett Kahr is Senior Fellow at the Tavistock Institute of Medical Psychology in London and, also, Visiting Professor of Psychoanalysis and Mental Health in the Regent’s School of Psychotherapy and Psychology at Regent’s University London. A long-standing admirer of the Freud Museum, he worked as Deputy Director of the International Campaign for the Freud Museum between 1986 and 1987, shortly after the museum opened; and, subsequently, between 2011 and 2020, he served as a Trustee of both Freud Museum London and Freud Museum Publications. He is the author of fifteen books, including Life Lessons from Freud and, also, Coffee with Freud. His next book will be entitled Freud’s Pandemics: Surviving Global War, Spanish Flu, and the Nazis, based on his live webinar, which helped to raise money for the museum in the immediate aftermath of the COVID-19 emergency.

Copyright © 2020, 2021, by Professor Brett Kahr. Please do not quote without the permission of the author.

References

Arnold, Catharine (2018). Pandemic 1918: The Story of the Deadliest Influenza in History. London: Michael O’Mara Books.

Barry, John M. (2004). The Great Influenza: The Epic Story of the Deadliest Plague in History. New York: Viking / Penguin Group, Penguin Group (USA).

Blanton, Smiley (1971). Diary of My Analysis with Sigmund Freud. New York: Hawthorn Books.

Burlingham, Michael John (1989). The Last Tiffany: A Biography of Dorothy Tiffany Burlingham. New York: Atheneum / Macmillan Publishing Company.

Cameron, Laura, and Forrester, John (1999). ‘A Nice Type of the English Scientist’: Tansley and Freud. History Workshop Journal, 48, 62-100.

Dorsey, John M. (1976). An American Psychiatrist in Vienna, 1935-1937, and His Sigmund Freud. Detroit, Michigan: Center for Health Education.

Eissler, Kurt R. (1952). Interview with Dr. Adolph Stern: November 13, 1952. Unpublished Transcript. Box 122. Folder 10. Sigmund Freud Papers. Sigmund Freud Collection. Manuscript Reading Room, Room 101, Manuscript Division, James Madison Memorial Building, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C., U.S.A.

Eissler, Kurt R. (1953). Sonoband No. 17: Sir Arthur Tansley. Summer 1953. Unpublished Transcript. Box 122. Folder 12. Sigmund Freud Papers. Sigmund Freud Collection. Manuscript Reading Room, Room 101, Manuscript Division, James Madison Memorial Building, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C., U.S.A.

Forrester, John, and Cameron, Laura (2017). Freud in Cambridge. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Forsyth, David (1920). Psycho-analysis of a Case of Early Paranoid Dementia. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine, Section of Psychiatry, 13, 65-81.

Forsyth, David (1922). The Technique of Psycho-Analysis. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner and Company.

Freud, Martin (1957). Glory Reflected: Sigmund Freud – Man and Father. London: Angus and Robertson.

Freud, Sigmund (1919a). Letter to Ernest Jones. 18th April. In Sigmund Freud and Ernest Jones (1993). The Complete Correspondence of Sigmund Freud and Ernest Jones: 1908-1939. R. Andrew Paskauskas (Ed.). Frauke Voss (Transl.), pp. 340-341. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Freud, Sigmund (1919b). Letter to Max Eitingon. 12th October. In Sigmund Freud and Max Eitingon (2004). Briefwechsel: 1906-1939. Erster Band. Michael Schröter (Ed.), pp. 163-165. Tübingen: edition diskord.

Freud, Sigmund (1919c). Letter to Karl Abraham. 2nd November. In Sigmund Freud and Karl Abraham (2009). Briefwechsel 1907-1925: Vollständige Ausgabe. Band 2: 1915-1925. Ernst Falzeder and Ludger M. Hermanns (Eds.), pp. 632-633. Vienna: Verlag Turia und Kant.

Freud, Sigmund (1920). Letter to Karl Abraham. 31st October. In Sigmund Freud and Karl Abraham (2009). Briefwechsel 1907-1925: Vollständige Ausgabe. Band 2: 1915-1925. Ernst Falzeder and Ludger M. Hermanns (Eds.), pp. 672-673. Vienna: Verlag Turia und Kant.

Freud, Sigmund (1933). Neue Folge der Vorlesungen zur Einführung in die Psychoanalyse. Vienna: Internationaler Psychoanalytischer Verlag.

Grinker, Roy R. (1940). Reminiscences of a Personal Contact with Freud. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 10, 850-854.

H.D. [Hilda Doolittle] (1945a). Writing on the Wall. [Part I]. Life and Letters To-Day, 45, 67-98.

H.D. [Hilda Doolittle] (1945b). Writing on the Wall: (Continued). [Part II]. Life and Letters To-Day, 45, 137-154.

H.D. [Hilda Doolittle] (1945c). Writing on the Wall: (To Sigmund Freud). [Part III]. Life and Letters and The London Mercury and Bookman, 46, 72-89.

H.D. [Hilda Doolittle] (1945d). Writing on the Wall: (To Sigmund Freud). [Part IV]. Life and Letters and The London Mercury and Bookman, 46, 136-151.

H.D. [Hilda Doolittle] (1946). Writing on the Wall: (To Sigmund Freud). [Part V]. Life and Letters and The London Mercury, 48, 33-45.

H.D. [Hilda Doolittle] (1956). Tribute to Freud: With Unpublished Letters by Freud to the Author. New York: Pantheon / Pantheon Books.

Jones, Ernest (1919). Letter to Sigmund Freud. 1st July. In Sigmund Freud and Ernest Jones (1993). The Complete Correspondence of Sigmund Freud and Ernest Jones: 1908-1939. R. Andrew Paskauskas (Ed.). Frauke Voss (Transl.), p. 350. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Jones, Ernest (1953). The Life and Work of Sigmund Freud: Volume 1. The Formative Years and the Great Discoveries. 1856-1900. New York: Basic Books.

Kardiner, Abram (1977). My Analysis with Freud: Reminiscences. New York: W.W. Norton and Company.

May, Ulrike (2006). Freuds Patientenkalender: Siebzehn Analytiker in Analyse bei Freud (1910-1920). Luzifer-Amor, 19, Number 37, 43-97.

May, Ulrike (2007a). Neunzehn Patienten in Analyse bei Freud (1910-1920): Teil I: Zur Dauer von Freuds Analysen. Psyche, 61, 590-625.

May, Ulrike (2007b). Neunzehn Patienten in Analyse bei Freud (1910-1920): Teil II: Zur Frequenz von Freuds Analysen. Psyche, 61, 686-709.

Menaker, Esther (1989). Appointment in Vienna: An American Psychoanalyst Recalls Her Student Days in Pre-War Austria. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Oberndorf, Clarence P. (1953). A History of Psychoanalysis in America. New York: Grune and Stratton.

Oberndorf, Clarence P. (1958). An Autobiographical Sketch. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Infirmary and Clinic.

Roazen, Paul (1990). Tola Rank. Journal of the American Academy of Psychoanalysis, 18, 247-259.

Roazen, Paul (2000). Oedipus in Britain: Edward Glover and the Struggle Over Klein. New York: Other / Other Press.

Stern, Adolph (1922). Some Personal Psychoanalytical Experiences with Prof. Freud. New York State Journal of Medicine, 22, 21-25.

Wortis, Joseph (1940). Fragments of a Freudian Analysis. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 10, 843-849.

Wortis, Joseph (1954). Fragments of an Analysis with Freud. New York: Simon and Schuster.