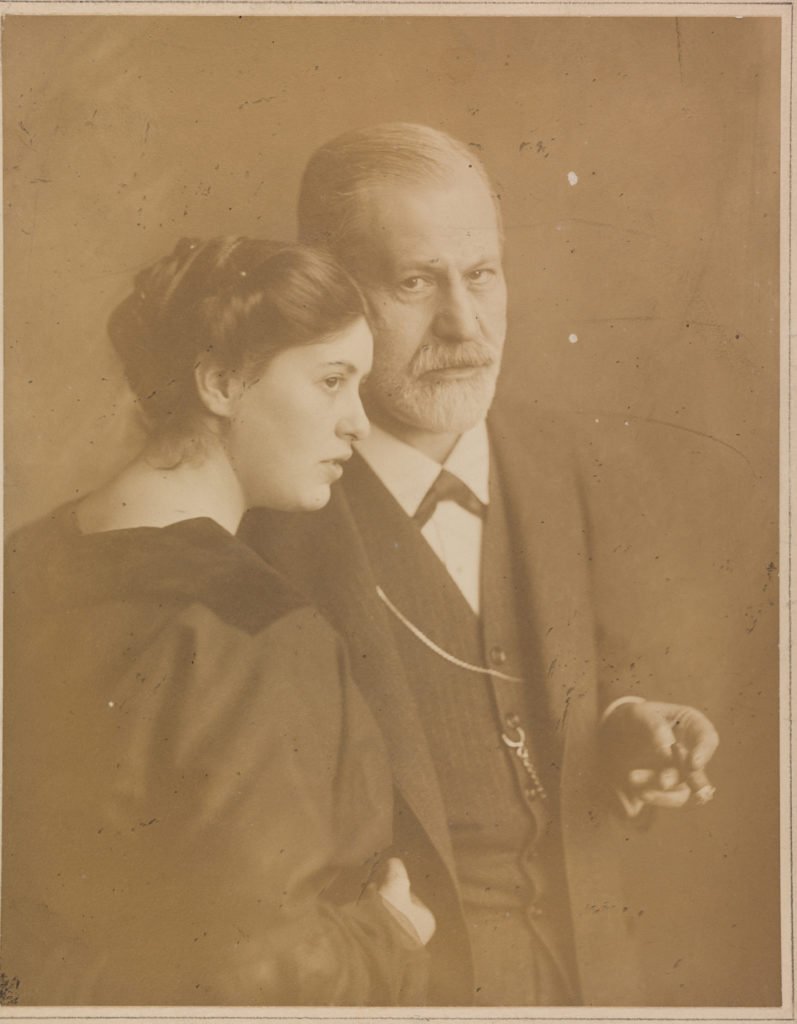

Portrait photograph of Sigmund and his daughter Sophie Freud, taken in Hamburg, c.1913 [IN/0055]

Beyond the Pleasure Principle – A Virtual Reading Experience

The importance of social rituals, those shared activities which can either be acknowledged or tacit, has been thrown into relief during this ongoing period of lockdown. Friday nights at the Freud Museum used to be the scene of such a ritual, it was when a group of staff and volunteers would meet together in the main office (Anna Freud’s old consulting room) in order to read Freud’s texts together. Rituals can, of course, evolve, indeed they are unlikely to survive unless they do. In this manner the reading group has also adapted to current environmental pressures, and now meets once a week virtually, via Zoom.

The text we are currently reading is one of Freud’s most challenging and controversial works, Beyond the Pleasure Principle, which is celebrating its centenary this year. Although the date of its publication was September 1920, Freud reported that the text was finished in May of that year, the same month that our group will finish reading it. Drawing comparisons such as this may appear to be tangential, but Beyond the Pleasure Principle does of course have a great deal of relevance to our current situation, written as it was during the Spanish Flu pandemic.

Qualifiers and Speculations

Beyond the Pleasure Principle is a text that is full of surprises, qualifiers and ‘speculations’, a term which appears at regular intervals throughout the text, ‘What follows is speculation, often far-fetched speculation, which the reader will consider or dismiss according to his individual predilection’, Freud writes, at the beginning of part IV. Drawing on personal experience, microbiology and speculative philosophy among other things, Freud’s text can appear disjointed and patchwork at times, perhaps overdetermined, almost in the manner of a dream.

How do we draw out meaning from a text which appears to be overdetermined? By applying the methodological framework that Freud outlined in The Interpretation of Dreams, we might find the key to interpreting the complexities of Freud’s most speculative text. Indeed, literary theory, engaging with the findings of psychoanalysis, recognises the notion of manifest and latent meaning in a dream, which it translates into text and subtext in the reading of texts. If we were to apply the terms of text and subtext to Beyond the Pleasure Principle, what might we discover? There is a spectre haunting Freud’s text, one which makes a fleeting appearance in a footnote towards the end of part II, after Freud had been describing the famous ‘fort-da’ game that a young child who ‘lived under the same roof’ as him had invented. The footnote begins as follows, ‘When this child was five and three-quarters his mother died.’ A dispassionate footnote, written from the position of a disinterested observer, but one which inscribes a moment of great trauma for Freud. The subtext to the text of part II marks the death of the child’s mother, who is also Freud’s favourite daughter Sophie, who died in the Spanish Flu pandemic.

‘Sense of Mastery’

If we think of Freud’s text as analogous to a dream, we would also expect to discover a wish. How could the writing and completion of this text, marked as it is by such tragedy, amount to the fulfilment of a wish? When describing the ‘fort-da’ game played by his grandson Ernst, Freud suggests that the game is a symbolic reconfiguration of the trauma experienced by the child at the mother’s unexpected and inevitable absence. The throwing away of a wooden reel, which the child accompanies with the utterance ‘fort’ (gone) represents the mother’s absence, whilst the mother’s return is represented by the return of the wooden reel, accompanied by the exclamation ‘da’ (here). In staging the absence and return of the mother in the game of the wooden reel, by translating the trauma into a ‘game’, the child gains a sense of ‘mastery’ over the situation; he has willed the absence and he will determine the return. It all happens on his terms.

This ‘sense of mastery’ is one of the main topics discussed in Beyond the Pleasure Principle, when Freud attempts to explain the motives behind the ‘compulsion to repeat’ traumatic situations which at first would seem to call into question the ubiquity of the Pleasure Principle. Might the activity of writing this text have been Freud’s own attempt to gain mastery over the trauma of his daughter’s death? Can this act of writing be compared to the ‘fort-da’ game staged by Freud’s grandson Ernst? Does psychoanalysis inadvertently slide into the realm of psychobiography by following such a pathway? Freud himself certainly anticipated such an interpretation, which he attempted to forestall in a letter to Max Eitingon, dated July 1920, ‘The beyond is finally finished. You will certify that it was half finished when Sophie was alive and flourishing’. If Freud had finished the ‘fort-da’ passage before Sophie was taken ill, how can we establish a causal connection between her death and Freud writing part II? We seem to be entering the field of speculation here, to have joined Freud in the role of ‘speculator’ that he adopts throughout the text.

Spectres

What we do know is that Freud’s great speculative breakthrough, in which he delineates his new dual instinct (drive) theory centred on Eros and the death instinct, appears in part VI of the text, which was definitely completed after Sophie’s death. Indeed, we also know that Freud’s paper The Uncanny was written in the middle of the compositional process of Beyond the Pleasure Principle, a text which deals, amongst other things, with hauntings, doppelgängers and intimations of death. Another spectre which haunts Freud’s great speculative metapsychological text perhaps?

How can a text maintain its internal cohesion and integrity under the strain of so much trauma and so many intrusions? Derrida’s brilliant analysis of Beyond the Pleasure Principle in The Postcard hints at other spectres that may haunt the text, other aporias which threaten its internal stability and open up under close textual analysis. Perhaps, in the spirit of deconstruction, the true spectre haunting Beyond the Pleasure Principle is the spectre of textual cohesion and authorial intention. Perhaps a reading always implies a re-reading, that it always involves the Nachleben or ‘afterlife’ of a text, that the impacts and meanings that a text can offer operate on the model of ‘deferred action’ or Nachträglichkeit. Perhaps every reading is a process of retranslation and rediscovery, and that the search for the ultimate and authorial meaning of a text is a seductive yet ultimately futile quest.

Reading Beyond the Pleasure Principle during our current pandemic seems to shed a light on the mutual hauntings that texts and readings of texts can have on each other, the reflexive nature of reading, and that the temporal demarcations of past, present and future, are not so clearly defined as we may sometimes assume.

Beyond the Pleasure Principle and Other Writings – Sigmund Freud is available from the Freud Museum Shop.

Comments

Coud you kindly advise when the Museum might be open and whether the exhibition relating to Beyond the Pleasure Principle will still be on display

Thank you

The Museum is open every Wednesday, Saturday and Sunday from 10:30 – 17:00. Our exhibition 1920/2020: Freud and Pandemic is on until 12 September 2021.

All our visitor information is here: https://www.freud.org.uk/visit/