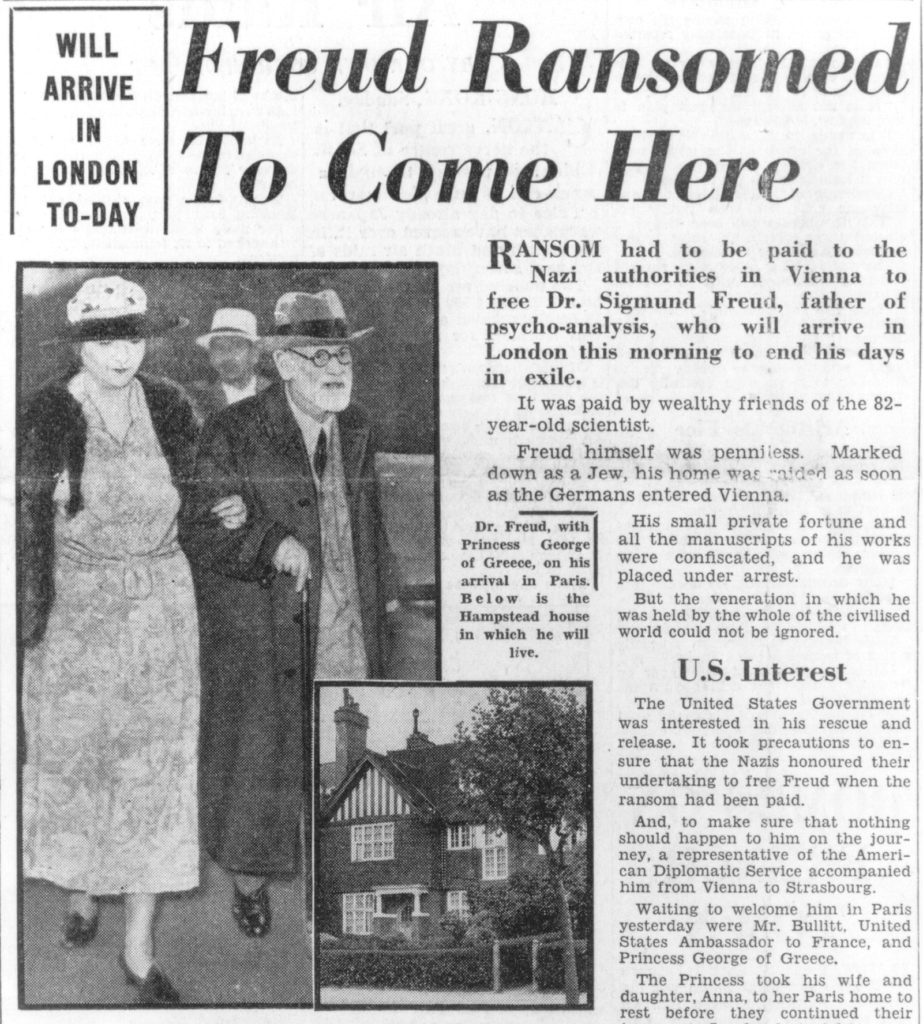

Daily Herald, 6 June 1938 [PC/10/025]

‘England’ as Home

“Our reception was cordial beyond words. We were wafted up on the wings of a mass psychosis. … In short, for the first time and late in life I have experienced what it is to be famous.”

Letter to Alexander Freud, June 22, 1938.

“…you cannot have known that since I first came over to England as a boy of eighteen years, it became an intense wish phantasy of mine to settle in this country and become an Englishman. Two of my half-brothers had done so fifteen years before. But an infantile phantasy needs a bit of examination before it can be admitted to reality.”

Letter to H.G. Wells, July 16, 1938.

Why did Freud choose England as his final home? And how did it become ‘home’ in a psychical as well as physical sense?

Think of yourself as a customs officer, asking Freud for his passport and identity papers during that long journey into exile in the early days of June 1938. What nationality was he? The obvious answer would be Austrian, but Austria had only been created by the treaty of St. Germain in 1919, and disappeared in 1938.

Perhaps he was Czech. After all, he was born in Moravia, although then it was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. He no doubt at times saw himself as a German, and in response to his upbringing and the anti-semitism he encountered along the way, as a Jew. So we have a German-identified, culturally assimilated Jew, born in what is now the Czech Republic and living in Vienna, a town he claimed to detest with an almost physical loathing.

Such prosaic facts miss the spiritual and emotional resonances of this topography. We might say that his heart was in Rome, recurring as it did in his dream-life and his travels as a place to be reached after much difficulty, and finally ‘conquered’. Or that he found his mythic origins in Egypt, the birth-place of Moses, which Freud could only reach himself through the graven images of ancient gods which filled his place of work. Or that it was his own birth-place in Freiberg (now Pribor in the Czech Republic) that he yearned for, as some lost paradise to which he was always trying to return. And finally there was England. Another significant place that we must somehow fit into this array.

Picture postcard of a view over Pribor [IN/0624]

Fog and Rain, Drunkenness and Conservatism

Certainly Freud found something congenial about England ‘in spite of the fog and rain, drunkenness and conservatism’ as he wrote after his first visit. Freud felt temperamentally attuned to the place almost despite himself. For some reason he felt at home here; feeling an almost instinctual rapport with the country. In later years, Freud the psychoanalyst would unhesitatingly call this feeling ‘an infantile phantasy’. His first home and his last were thus connected in his mind in some way.

He came to England as a ‘boy of eighteen’, and his wish was ‘to become an Englishman’. We might suppose that it was the culture of England which attracted this well educated young man. In particular there was a culture of literature and science marked by two names, William Shakespeare and Charles Darwin; or rather by two books, Hamlet and The Origin of Species. Despite the fog and conservatism, this was the land which contained two heroic intellectual figures for Freud who represented two aspects of his own being – the ‘imaginative writer’ and the ‘scientist’. In Freud’s own creative work, thinking and feeling are joined together. There is a rhythm of control and the abandonment of control – drunkenness and conservatism, perhaps. England was in some ways a mythical place which gave due weight to both of the tendencies which Freud found within himself, and which we find today in psychoanalysis, as both a theory and therapy.

Sigmund Freud in London, 1938 [IN/0121]

The half brothers left; and with them went Freud’s admired older playmate and fighting companion, his ‘nephew’ John, the son of his much older half-brother Emanuel. Did this separation awaken echoes of the death of his brother Julius a year earlier? Soon after, Freud himself was uprooted from his birthplace and taken to Vienna. He sees gas lights for the first time at the railway station, and they seemed to young Sigmund, influenced by the Catholic Czech nanny who looked after him in infancy, to be like the souls of the damned burning in hell. Perhaps he felt this move as a kind of punishment for something. Whatever the case, it seems that Freiberg and England became intimately connected. In later life he seemed to idealise both places in a nostalgic and unrealistic way – as if the infantile amnesia that Freud discovered and made one of the basic justifications for his theories does not only leave a blank space in our memories but a residue of idealisations, ‘screen memories’ and nostalgic yearnings.

Other Place

It appears, then, that Freiberg was an encapsulated ideal in the past, and that England was an ideal ‘other place’ in the future, known only vicariously at first through the words of others, as the place to which John and his family had disappeared. Freud’s journey to England may therefore also be a return to something; a return to some idyllic phantasy of childhood. The detour of his life had brought him back in some ways to the beginning. He was surrounded by the ‘whole family’ again as he was as a three year old. He knew once again what it meant to be ‘famous’ – as he was once his mother’s ‘undisputed favourite’ during infancy. And once again he could look out from his room onto the greenery of a beautiful garden – a symbolic return to the earth and to the countryside of his birthplace – rather than the concrete courtyard of Berggasse 19.

But even as he arrived in England he was pining for Vienna. In a letter to Max Eitingon dated the day of his arrival on the 6 June 1938, he wrote: ‘The feeling of triumph on being liberated is too strongly mixed with sorrow, for in spite of everything I still greatly loved the prison from which I have been released.’ No doubt it is true that Freud’s relationship to Vienna, like all relationships, was an ambivalent one. The mind, in his view, is in conflict with itself and in an endless struggle with the ‘heart’. But there is something ‘irrational’ here that goes beyond the conflict of love and hate. It is almost as if he was addicted to ‘yearning’; as if there had to be ‘another place’ that was lost and grieved for while living his actual life through an endless succession of ‘substitutes’. I am reminded of Wagner’s tragic hero, Tristan, whose mother died in childbirth and who could find no peace from a state of endless yearning. Or Emily Dickinson’s poem, To fill a Gap, which encapsulates the tragic impossibility in a few lines.

To fill a Gap

Insert the Thing that caused it—

Block it up

With Other—and ’twill yawn the more—

You cannot solder an Abyss

With Air.

A Bit of Examination

Would it be a step too far (even for the wild speculation I am indulging in now) to suggest that this emotional vacillation underlies Freud’s dialectical mode of thinking? Freud argues with himself, taking first one point of view then an opposite one; a thinking process that he sometimes explicitly reveals in his writing by evoking the figure of the ‘friendly critic’ to establish dialogue.

So it is not surprising that Freud, speaking of his ‘intense wish phantasy’ to become an Englishman in his letter to HG Wells, should continue by reminding us that an infantile phantasy needs ‘a bit of examination’ before it can be admitted to reality. He was, after all, a psychoanalyst, and in a life of continual self-analysis he subjected himself more than anyone to the science that he created.

“This England – you will soon see for yourself – is in spite of everything that strikes one as foreign, peculiar, and difficult, and of this there is quite enough – a blessed, a happy country inhabited by well-meaning, hospitable people. At least this is the impression of the first weeks. Our reception was cordial beyond words. We were wafted up on the wings of a mass psychosis. … There were letters from friends, a surprising number from complete strangers who simply wanted to express their delight at our having escaped to safety and who expect nothing in return. In addition of course hordes of autograph hunters, cranks, lunatics, and pious men who send tracts and texts from the Gospels which promise salvation, attempts to convert the unbeliever and shed light on the future of Israel. Not to mention the learned societies of which I am already a member, and the endless number of Jewish associations wanting to make me an honorary member. In short, for the first time and late in life I have experienced what it is to be famous.” Letter to Alexander Freud, Freud’s brother, June 22, 1938

Comments

“In short, for the first time and late in life I have experienced what it is to be famous.” Wonderful!