Home Is Where The Heart Is – Part 1

Due to the current guidelines around social distancing, many of us have recently had to become more acquainted with our own homes. Whilst we may have felt a long-held desire to spend more time at home, we are also perhaps experiencing a strange feeling of uneasiness accompanying the fulfilment of this particular wish. In his short paper, ‘Some Character-Types met with in Psychoanalytic work’ (1916), Freud describes a group of patients and characters from literature who are ‘wrecked by success’, who experience overwhelmingly negative feelings and inhibitions around ‘getting what they wanted’. Some wishes, he argues, are tolerable to the ego if they ‘remain in phantasy’, but the ego will ‘defend itself hotly’ against them if they approach fulfilment and ‘threaten to become reality’. The old adage that warns us to be ‘careful what we wish for’ seems applicable to our current situation.

Social distancing measures have produced the side-effect that, for many of us, our homes have taken on a much more complex emotional charge than when they existed as a place to escape to in fantasy.

Home is where one starts from. As we grow older

The world becomes stranger, the pattern more complicated

Of dead and living. Not the intense moment

Isolated, with no before and after,

But a lifetime burning in every momentT. S. ELIOT

‘East Coker’, Four Quartets

The first sentence of this passage towards the end of Eliot’s ‘East Coker’ is also the title of a collection of essays by Winnicott, which explore the individual’s place within the family and society as a whole. The lines suggest to us the idea that home is a starting place, a place of innocence that our experience of the world forces us to leave behind. The ‘strangeness’ and complexity of the world is immanent in every experience and activity we are implicated in. ‘A lifetime burning in every moment’. Home is then not a place that we can return to in a state of childlike innocence. In fact we may experience home more in the sense that Philip Larkin envisaged it,

Home is so sad. It stays as it was left,

Shaped to the comfort of the last to go

As if to win them back. Instead, bereft

Of anyone to please, it withers so,

Having no heart to put aside the theftAnd turn again to what it started as,

A joyous shout out to how things ought to be,

Long fallen wide. You can see how it was:

Look at the pictures and the cutlery.

The music in the piano stall. The vase.PHILIP LARKIN

‘Home is so Sad’, The Whitsun Weddings

Larkin’s poem paints the home as an unfulfilled promise, a reminder of something once hoped for but now lost, ‘A joyous shout of how things ought to be, Long fallen wide’. Freud’s seminal paper ‘The Uncanny’ (1910), helps to illuminate the complex and ambivalent relationship that we have to our own homes. The German title of the paper, ‘Das Unheimliche’, literally translates as ‘the unhomely’, and in the first part of the text, through a linguistic analysis of the opposites heimlich-unheimlich, Freud shows how the two words, rather than being opposites, somehow blend into one another, exposing the relationship as a false binary. ‘Thus heimlich is a word the meaning of which develops in the direction of ambivalence, until it finally coincides with its opposite, unheimlich. Unheimlich is in some way or other a sub-species of heimlich’.

The ambivalence that Freud discovered in this concept is fundamental to the psychoanalytic world view. That opposites can exist side by side, that ‘the homely’ can at the same time be the ‘unhomely’, hints at why Larkin’s ‘music in the piano stall. That vase’, can contain such emotional charge. If, as Freud suggested, ‘the ego is not master in its own house’, then perhaps the physical spaces that we inhabit, our own homes, exist for us on the continuum of the homely-unhomely. Freud’s paper ‘The Uncanny’, is full of doublings, mirror images and hauntings, which can help us to understand why the fulfillment of our collective wish to spend more time at home may not be as trouble-free as was once thought.

Comments

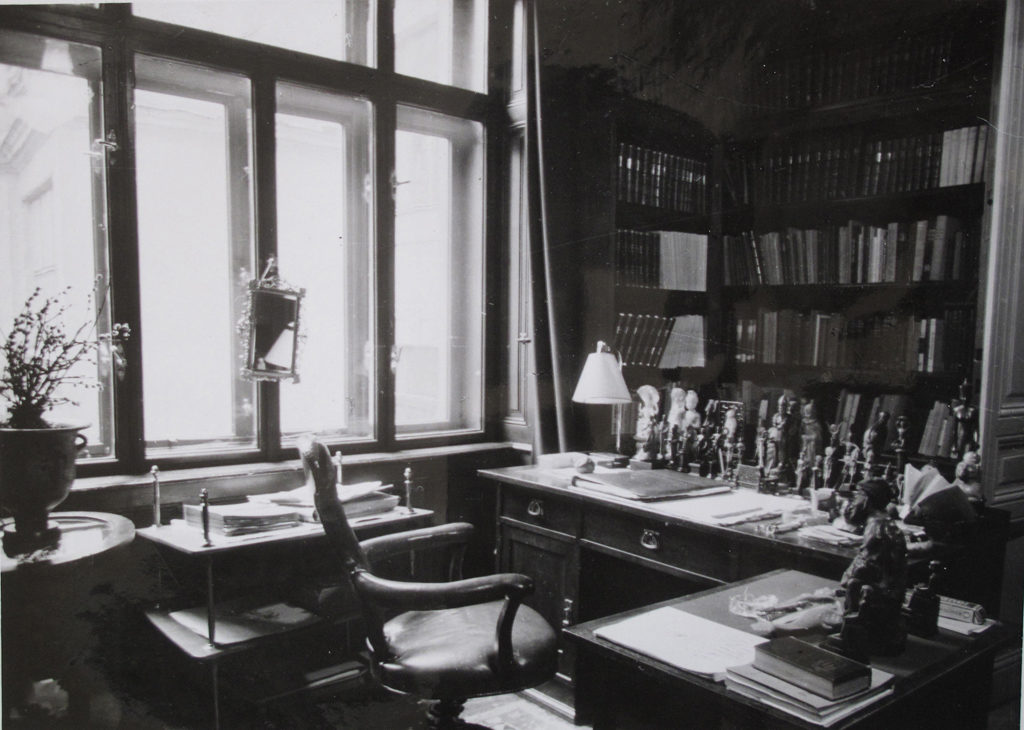

When I compare Freud’s original study at Bergasse 19 to 20 Maresfield Gardens, I experience the sentiment in keeping with Sergei Pankijeff’s comment, that the Bergasse 19 study gives a ‘feeling of sacred peace and quiet’. The study at Bergasse 19, being somewhat somber and yet tastefully furnished with ancient artifacts, has the stamp of the seriousness of psychoanalysis. It is a space where the exploration of the unconscious, requiring thoughtful reflection and the deepening of feeling, can truly happen. The study at 20 Maresfield Gardens is bright, cheerful, and in keeping with a modern lightheartedness of ‘smile and be happy’. Would an analysand at 20 Maresfield Gardens take seriously Freud’s sobering comment: ‘the best we can hope for is to convert hysterical misery into common unhappiness.’ ? Or, would upon hearing the latter comment, come to experience psychoanalysis as failing to deliver the wished for salvation from the realities of displeasure to unbounded optimism and joy!

Thank you,

Frank J. Marchese, PhD

Dept. of Psychology

York University

Toronto, Canada

I had a really unheimlich experience at the Freud Museum. I was alone in one of the upstairs rooms when I heard, to my horror, footsteps coming from above my head. It had never occured to me that there might be other floors in Freud’s house, peopled with, well, who knew? I fled to the homeliness of the Finchley Road.