When young Nathaniel quizzes his nurse about the mysterious Sandman his mother had told him about, he receives a gruesome reply: ‘He’s a wicked man, who comes to children when they won’t go to bed, and throws a handful of sand into their eyes… He puts their eyes in a bag and carries them to the crescent moon to feed his own children.’

Nathaniel’s childhood terror of the Sandman, whom he comes to associate with his father’s sinister acquaintance Coppelius, lies at the heart of E. T. A. Hoffmann’s unsettling 1816 short story Der Sandmann. Credited by Freud with evoking a “quite unparalleled atmosphere of uncanniness”, Hoffmann’s eerie tale of madness, unreliable memories, and a young man tormented by the past becomes one of the key references in his 1919 essay The Uncanny.

‘The Sandman’ installation at the Freud Museum London. Elizabeth Dearnley 2019

E. T. A. Hoffmann

Today Hoffmann is perhaps best known for inspiring Tchaikovsky’s The Nutcracker, as well as Offenbach’s fantastical opera The Tales of Hoffmann. A leading figure of German Romanticism, his spikily macabre fantasies populated by dolls, automata, doppelgängers and optical illusions reflect many of the movement’s wider interests in dreams, childhood and yearning for the past, and are far creepier than the fairy tales gathered by his contemporaries Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm. His 1817 collection Die Nachtstücke (‘The Night Pieces’) – published five years after the Grimms’ Children’s and Household Tales – brings together a number of his horror tales, beginning with The Sandman.

In Dreams

The Sandman can be found in various folklore traditions in both benign and more malevolent guises; Hans Christian Andersen’s Ole Lukøye (‘Ole Shut-Eye’) is a kindly being who holds a magical dream-enhancing umbrella over the heads of sleeping children, while the French-Canadian bogeyman Bonehomme Sept Heures (‘seven o’clock man’) stalks from house to house carrying a sack into which he stuffs any youngsters unlucky enough to be awake when he arrives. More recent incarnations include Neil Gaiman’s groundbreaking Sandman comic book series, as well as Roy Orbison’s 1963 syrupy ballad In Dreams, which credits a ‘candy-coloured clown they call the Sandman’ with sprinkling the stardust allowing the song’s narrator to drift away to his lost love – reimagined to luridly nightmarish effect in David Lynch’s Blue Velvet.

In Hoffmann’s hands, the Sandman assumes the terrifying form of an unstoppable childhood monster, capable of burning Nathaniel’s eyes with red-hot coals and causing the death of his father. Freud’s essay suggests that the tale’s most uncanny effects come from its ability to capture the horror of losing one’s eyes, as well as Coppelius’ role as the father’s dark double, concluding that Hoffmann is “the unrivalled master of conjuring up the uncanny.”

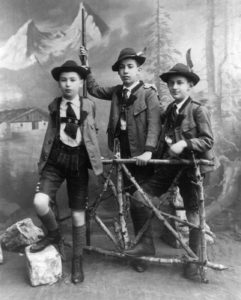

Freud’s sons: Ernst, Jean Martin and Oliver Freud c. 1900 [Freud Museum Collection IN264]

Reimagining Nathaniel

My reworking of The Sandman for The Uncanny: A Centenary updates the narrative to take place in 1919 and the years leading up to it, reimagining Nathaniel and his parents as friends of the Freud family circle. Freud’s essay was published in the aftermath of the First World War, an experience which haunted Freud’s sons and millions of others who fought in the trenches; I wanted to explore some of the ideas in Hoffmann’s story within this wider historical context. In my version, Nathaniel returns from the Front to a house where he had spent much of his childhood, hoping to piece together the fragments of his life and confront the Sandman one more time. Audiences are guided through Freud’s house in Maresfield Gardens by a 15-minute story narrated by Nathaniel (available online via the Uncanny iOS or Android app), until they reach the room where Nathaniel used to stay.

Childhood memories

Viennese toy theatre, Museum of Childhood

In recreating Nathaniel’s childhood memories within Anna Freud’s old bedroom, my aim was to make it feel like stepping into an old photograph – a ghostly, dreamlike space that was both cosy and uncosy, heimliche and unheimliche, somewhere between Where the Wild Things Are and The Cabinet of Dr Caligari (which came out in 1920, the year after The Uncanny was published). I also spent quite a bit of time in the more uncanny corners of the Museum of Childhood and Pollock’s Toy Museum looking at old dolls, as well as taking visual cues from Strewwelpeter, funfairs, and horror and fantasy films like J. A. Bayona’s The Orphanage, Jennifer Kent’s The Babadook and Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. Nathaniel was brilliantly brought to life in the recording booth by Timothy Allsop, while Tamsin Dearnley wove together a haunting soundscape of jangling musical boxes, ticking clocks and eerie singing to evoke his dreams, nightmares and memories.

For me, the Sandman also provides a useful way of thinking about dealing with mental illness or trauma. In Hoffmann’s tale it’s unclear how much of what Nathaniel is experiencing is actually happening, and how much is due to his own inner demons. But in many ways, it doesn’t matter; the Sandman is real to Nathaniel. Rather than denying the existence of the Sandman, I wanted to focus on how he could be defeated, or at least lived with.

Like many myths and folktales, The Sandman gives unspeakable fears a shape and a name – and in doing so, suggests ways of coming to terms with them. We all see the Sandman sometimes – but perhaps we can learn to look him in the eye.

Elizabeth Dearnley is an artist, folklorist and maker whose work centres around interactive, collaborative storytelling and engagement with public spaces.