Translation and Psychoanalysis: a 2-day conference organised by the SITE for Contemporary Psychoanalysis and the Freud Museum. 8-9 June 2019. More info >>

James Strachey’s celebrated but contested English translation of Freud’s works is the subject of longstanding debates.

To what extent does Stratchey render Freud’s vernacular German too technical, too scientific? What have been the consequences of this for the reception and development of the theory and practice of psychoanalysis in the English-speaking world?

Etymologically, translation means ‘to carry over’.

Like Freudian metapsychology, it is a dynamic, topographical and economic notion, connoting the circulation across borders, of elements from one place to another and the interaction and influence these crossings have upon the elements of exchange and their respective sites of transmission.

No wonder then, that Stratchey’s ‘English Freud’ provokes such disagreement: inevitably, senses or associations Freud intended are lost whilst new ones are gained, as ideas circulate from one intellectual and cultural system of meaning to another. Translation is bivalent: it simultaneously unveils things that are hidden and inaccessible, even as it obscures and masks others.

Is it possible to argue that the metaphor of translation operates as a ‘hidden organising principle’, underpinning Freud’s theoretical speculations and clinical thinking?

Considering translation’s close proximity to metapsychology, is it possible to argue that the metaphor of translation operates as a ‘hidden organising principle’, underpinning Freud’s theoretical speculations and clinical thinking? To take only one possible example amongst many, the metaphor of translation is invoked explicitly in Freud’s theory of the mechanism of repression, used to account for the formation of the unconscious and to elucidate the genesis of hysterical symptoms.

Clinical work itself might be comprehended via various appeals to ideas of translation. The central clinical concepts of transference and interpretation are perhaps only the most obvious. Could it be for these reasons that certain contemporary and postmodern schools of psychoanalysis have recently attempted to argue that psychoanalysis is best grasped as a school of hermeneutics?

Broader cultural questions

From the numerous linguistic and textual challenges arising when re-presenting psychoanalysis to audiences outside of its ‘mother tongue’, via metapsychology and ‘classical’ clinical work, the central relationship between psychoanalysis and translation readily opens out onto broader cultural and intellectual questions. What, for instance, of the actual geographical migration of psychoanalysis across multiple national borders, its perilous journey in the age of World Wars, and its very different receptions within diffuse social, economic and intellectual climates?

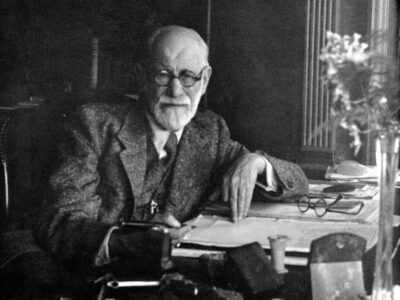

Freud developed psychoanalysis in a febrile political climate fostering an avant-garde artistic and intellectual atmosphere.

Freud’s intellectual heritage was largely – if not exclusively – Jewish central European, with strong traditions of philosophical rationalism and idealist epistemologies. Working in fin-de-siècle ‘Red’ Vienna, Freud developed psychoanalysis in a febrile political climate fostering an avant-garde artistic and intellectual atmosphere.

In Britain however, those initially drawn to Freud read his work against a political backdrop of Edwardian and post-Edwardian social conservativism at home and the decline of Imperialism and Empire abroad, imbued with traditions of philosophical positivism and epistemological empiricism.

To what extent did this very different milieu contribute to many of the significant alterations to the ‘new science’ of psychoanalysis, that have come to be significantly associated with British psychoanalysis? For example, the rise over the latter half of the twentieth century in the prominence of infant observation, normative theories of child development and attachment studies? And across the Atlantic – is it merely accidental that many central European Jewish analysts who emigrated to the United States, fleeing Nazi persecution, went on to develop models of psychoanalysis such as Ego Psychology, emphasising the adaptation of patients to the prevailing situations in which they found themselves?

Post-Freudian theory in context

Many analysts working in what is now associated with these British and American traditions, would be cautious and sceptical toward sociological speculation of this kind, perhaps preferring to suggest that alterations to classical technique and theory are an inescapable consequence of extending ‘classical’ psychoanalysis to clinical populations exceeding Freud’s initial work with the psychoneuroses.

Famously, Freud was doubtful that psychoanalysis was clinically appropriate for treating the psychoses. Although, almost since its inception, many influential analysts – in Europe, Britain, Latin and North America – have worked analytically with the psychoses, proposing various modifications to technique and theory along the way.

Similarly, work with forensic populations or with children and adolescents exhibiting what Winnicott termed the ‘Antisocial Tendency’, have prompted disagreements similar to those with the psychoses, over the extent to which psychoanalysis is feasible with hard to engage clinical populations. But is clinical work with such groups best considered as work with different psychopathologies? Or, instead, do such debates unknowingly cross yet other ‘invisible’ borders? Not between differentiated psychopathologies, but the challenges posed to a (largely if not exclusively) middle-class profession like psychoanalysis, used to working with (largely if not exclusively) middle-class patients sharing similar educational backgrounds.

Here, psychoanalysis needs to respond to urgent issues of social and economic injustice.

How might psychoanalysis clinically address and theoretically illuminate the devastating traumas adverse social and economic circumstance have on individuals? Are (largely if not exclusively) comfortably-off middle-class analysts, unaccustomed to material and social privations, best placed to understand and clinically translate the devastating experiences of those economically destitute and multiply excluded? What would a ‘working-class psychoanalysis’ look like?

Likewise, with issues pertaining to inter-cultural, -religious and -ethnic psychoanalysis, where personal and even long pre-personal histories of persecution and prejudice might be at the fore, how does psychoanalysis acknowledge and name unconscious biases in the transference and counter-transference? The same questions might also be raised regarding work with gender diverse and sexually non-normative individuals, whose lives are led on the margins of currently recognised and ratified gender and sexual identities and who might, therefore, pose uncomfortable challenges to traditional Western kinship systems and ideas surrounding what acceptably constitutes a socially recognisable family.

Finally, we might wonder about the stakes involved in what has been called ‘applied psychoanalysis’, when psychoanalysis is deployed as an analytical and diagnostic tool for understanding and elucidating artistic, cultural and political configurations. What happens when a clinical theory and praxis is lifted from the context in which it was developed, and used as a mode of comprehension and critique, with non-clinical aims, directed toward non-clinical objects? Is this possible? Or, is this where psychoanalysis reaches its limits, a final frontier and hard-border it cannot cross, a site psychoanalysis has to admit it is strictly non-translatable into?

All of these questions, and more, will be explored in what promises to be a highly exciting two-day conference.

Translation and Psychoanalysis: a 2-day conference organised by the SITE for Contemporary Psychoanalysis and the Freud Museum. 8-9 June 2019. More info >>