We are playing the guessing game. Is she an obsessive-compulsive nutcase with a passion for pointless rituals or is she an artist? She could, of course, be both.—Susannah Herbert, “Will the real Sophie Calle please stand up?”

Our last robbery had been a pair of red shoes too big for us to wear. Amelie kept the right shoe, and I kept the left.—Sophie Calle, Appointment

Alice Butler will be running a series of reading & writing workshops on Kleptomania, Art and Feminism at the Freud Museum this summer. Details >>

Case-making

To fray the genre of the case history I will begin with some loose definitions and swatches of quotation. Call them tactile texts.

Case has multiple meanings as a noun. It can refer to an event, a happening, a situation; which in its atomized singularity can also signify something much larger, the part of a whole. In medical language, we speak of ‘cases’ of breast cancer or HIV: individual instances of suffering within a more widespread disease. And in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, there were once ‘cases’ of hysteria, realised in the case histories of Sigmund Freud.

The history of hysteria is infected by the language and strategizing of ‘case’ making. It has contaminated the word’s related synonyms, felt in the misogyny of ‘nut-case’, a label used rhetorically by the journalist Susannah Herbert in her feature on the artist Sophie Calle, published in The Telegraph, 8 February 1999, to coincide with the artist’s parallel exhibitions in London at Camden Arts Centre and the Freud Museum.

In her 2007 essay “On the Case,” Lauren Berlant picks up on the precarious ambiguity of ‘the case’; its multiple functions: As genre, the case hovers about the singular, the general, and the normative.

The relationship between the singular and the general, which defines the case, can cause violent, hermeneutic acts, opening up the possibility of searching, even fictive links between cause and effect, between the particular event, and its exemplary power in the world. Case is both a thing that happened, and an action to take shape, as in ‘make a case for’. Put forward your findings. Construct your narrative. The closeness of ‘make’ and ‘make up’.

Writing weaves itself around the meaning of ‘case’ as well. From the 1580s, it was applied in the language of the printing trade, used to denote the wooden trays (because a case is also a container) that were used by compositors to store their types. And so ‘upper case’ for capital letters, and ‘lower case’ for small letters, entered our vocabulary as a result of where the glyphs were positioned with the printers’ cases. To be reminded of this ‘case’ history is to be reminded of just how much writing, fictionalising, making, and containing, goes on in the singular through to the general representation of hysterical patients.

Leaky containers

Freud may have stereotyped women as weavers as a result of their shamed anatomy, but the incomplete case history that emerged from his stunted treatment of the adolescent girl he named ‘Dora’, is also a woven fabric, full of strange, interloping threads and artificial embroideries, constructed by his phallic needle-cum-pen.

And yet the text-ile is also vulnerable to break, to unravel from his authored grasp, to fray. When someone else gets her hands on the case, who knows what might happen? The seams might buckle; the fibres might flake; holes might slowly emerge. Perhaps unsurprisingly, textile and text share the same etymological meaning: from the Latin texere—to weave. As Roland Barthes has pointed out, both materials are at once interwoven and unfinished. This curious interplay between tight and loose mesh invokes an enigmatic, open field, whereby meaning itself can fray. When the text-ile is only a fragment, this propensity to fray (to cause affray, to rewrite) becomes a political invitation as well as a physical property.

Dora, real name Ida Bauer, abruptly terminated her treatment after eleven weeks.

Freud wrote his case study (or was it a detective novel?) soon after, in January 1901. But it wasn’t fully published until 1905, by which time Freud had added footnotes, appliqued extra fragments of text and interpretation. Casing her all over; refusing to let her go.

Please try to bring her round to a better way of thinking, were the instructions Ida’s father reportedly uttered to Freud, after she complained of the incident by the mountain lake in which a family friend named Herr Zellenka (or ‘Herr K.’) sexually propositioned her, an accusation that he flatly denied. In the years after this traumatic encounter, Ida’s hysterical signs and symptoms spiralled, from a nervous cough and recurrent aphonia, to the writing of suicidal letters, bouts of fainting and amnesia.

Freud’s case history creates a melodramatic context for her illness, with narrative layers of deception and violence slowly revealed, including the revelation that ‘Dora’s’ father’s was also having an affair with ‘Frau K.’ and handed ‘Dora’ over to his friend in exchange for his complicity. Freud unpicks her scattered recollections in order to ‘find’ Dora’s secrets. His verdict? That Dora is haunted by her repressed, heterosexual desire for her father and for Herr K., which is unsheathed in the dream Dora relays to Freud, whereby her father wakes her up because of a fire, but her mother cannot leave without rescuing a prized jewel-box. To Freud’s symbolist mind, this is Dora (masquerading as her mother in the dream) gifting her sacred vulva to Herr K. (masquerading as her father).

The mystery case within the case. Or as Freud exclaims with relief and joy: the case has opened smoothly to my collection of picklocks.

But the analysis was broken off, left unfinished, not smooth at all. And just as hysteria was considered a leaky disease, originally defined by its etymological roots in the Greek hysterikos, meaning ‘of the womb, suffering in the womb’ (a leaky womb?), the case history is also a leaky container. It has holes, gaps, and inconsistencies, into which I, and others, have fallen. Case has Latin roots in casus, which means ‘a falling’.

Let these ‘fallen women’ speak, exploding the jewel-case open.

Sara Ahmed explodes: To be a container of damage is to be a damaged container; a leaky container. The feminist killjoy is a leaky container. She is right there; there she is, all teary, what a mess.

Standing at the intersection of psychoanalysis and feminism, the case of Dora, newly reopened, has pushed psychoanalysis from the consulting room into an ideological arena where it must engage in a dialogue with feminism and thus recover its radical promise.

Messing with her cases. Making a mess. Many feminist scholars, artists and writers have sought to rewrite the phallogocentric fragment of an analysis that is ‘Dora’s’ case history, refocusing our attention to ‘Dora’s’ desire for ‘Frau K.’; the repression of the mother; the desire for the maternal body; bisexuality; the social constructions of sexual difference, and the disruptive power of the hysteric to transform the family unit, to list just some of the arguments laid out in the 1985 essay-collection In Dora’s Case.

In sum: Standing at the intersection of psychoanalysis and feminism, the case of Dora, newly reopened, has pushed psychoanalysis from the consulting room into an ideological arena where it must engage in a dialogue with feminism and thus recover its radical promise.

There’s the desire to reopen the case. Hélène Cixous’s play Portrait of Dora published two years earlier burns with it, within which she gives a menacing voice back to the hysteric, a first person narrative. Dora becomes the subject of her own story; hers is a voice which rips through silence.

I slapped him, I cut short his intent. I understood his words.

When Dora cuts through Herr K.; Cixous cuts through Freud, cutting his case to pieces, in her cut-up rewriting.

And then there’s the desire to keep the case forever open, an open wound. Not a cure for a case but an unmaking. This is Sharon Kivland’s A Case of Hysteria, a large red tome of a container published by Book Works in 1999, which writes through Freud’s fragment, repeating and transforming and amending it, in a way that amounts to a performance of the reading process itself. An addiction—an obsessive compulsive disorder (like kleptomania?). Other voices intervene; there is a female detective, whose identity, like ‘Dora’, cannot be ‘solved’ in this case of translation-hysteria.

The point of her needle

That same year (when I was only ten years old), the French artist Sophie Calle intervened within texts of hysteria, when she made her own particular appointment with Freud for an exhibition at the Freud Museum.

For this installation (later made into an artist book by Violette Editions, with a delicious orange silk cover and sugar-pink letterpress title, delectable enough to steal, like the nineteenth century kleptomaniacs obsessed with crêpe de chine), Calle invaded Freud’s final home, at 20 Maresfield Gardens, which was also the space of his theory, a physical monument to psychoanalysis. She’s making a-point, a different sort of case, which is sharp and lethal, rewriting desire with her own needle and thread. Fraying Freud. Leaking blood.

The funny black-and-white portraits that begin the book encapsulate Calle’s kleptomaniac attitude: two (almost but not quite) mirror images of a man and a woman wearing the same coat. Calle flaunts her klepto-prize (the silver-haired psychoanalyst’s overcoat) and copies his pose, to dig deep inside her pockets for the tools she’ll use to rewrite him.

Paired with pithy texts on pale pink sheets, she displayed relics (many sartorial) from her own life, set amidst the interior of Freud’s home like tempting items in a department store. She also pilfered relics from Freud’s collection of antiquities, cloaked in the autobiographical stories she was telling: affectless fragments: little ‘pieces’ of her (more swatches) that hint at her childhood experiences and sexual relationships. These diaristic episodes cannibalise feelings of trauma, pain, masochism and vulnerability, in a deviant display of dark humour.

For example, beside one of Freud’s many amorous artefacts, a Narayait kneeling figure from Mexico, dated 100 BC-AD 250, is a short and snappy confession from Calle about the transformation of her breasts from flat to full. In the space of six months, spontaneously, I had proper tits: no treatments, no operations. A miracle. I swear.

In On Longing (1984), Susan Stewart contrasts the collection with the souvenir, finds that the collection offers example rather than sample, metaphor rather than metonymy. Like the case, the collection relies on a certain type of contiguity and classification, which in its desire for mastery, to me sounds so macho. As Stewart calls the collection: a mode of control and containment.

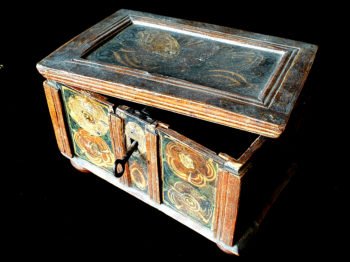

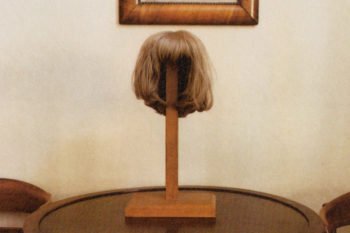

But here is Calle rewriting the urge to case, control, contain and collect, with her own intimate objects, a convulsive projection of selfhood, obsession and desire. The items in her dressing-up box, which comprise the irreplaceable objects listed in the museum’s loan agreement, also capture my kleptomaniac gaze:

A sandy blonde wig balances on an oak wood stand, which balances on a mahogany table. It is the same wig that Calle once wore as a stripper. Aged six and living with her grandparents: a daily ritual obliged me every evening to undress completely on my way up to the sixth floor, where I arrived without a stitch on… Twenty years later I found myself repeating the same ceremony every night in public, on the stage of one of the strip joints that line the boulevard in Pigalle. The blonde wig was her erotic disguise, and also the object that saved her, from her grandparents finding out.

Resting on a shelf painted white is a single high heel black stiletto. A court shoe of pared-back sophistication, this object from Calle’s life still shows signs of wear at its bended point. Torn from its twin sister, this thing appears cast-out, detached, a fetish and a trace. The pink sheet that frames it offers some biographical context, a story of girl-on-girl violence, not castration anxiety. On January 8, 1981, as I was sitting on the only chair in this trailer, one of my colleagues, to whom I refused to give my seat, tried to poke out my eyes with my high heel and ended up kicking me in the head.

Once again, upon a circular mahogany table: two black-and-white photographs, one echoing the other. Freud’s wedding photograph has been set a few inches back from Calle’s fake wedding photograph (stealing femininity, to use Leslie Camhi’s term), decorated with pretty mementos from the day: pieces of confetti, a wilting floral buttonhole, a fluffy white veil and two antique lace gloves. About this performance, Calle writes nothing was missing. I crowned, with a fake marriage, the truest story of my life.

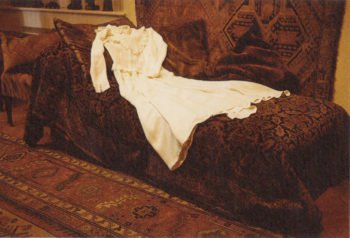

Then the shock of a cream, high-necked wedding dress with a Peter Pan collar lying supine on Freud’s sumptuous couch, that drawn-out bed, where patients drew their fantasies and dreams, from which Freud drew a picture of hysteria: many, many cases. Calle making her own case, her own appointment, with this deliberate invasion. She is a feminine phantom working in the opposite direction to the analyst’s weave, haunting him.

Calle pilfers things from her own life, destabilizing the space of psychoanalysis, with her own obsessive and possessive desire. Sometimes she even steals the love objects she once stole as an adolescent kleptomaniac… as in the ghostly sight of a singular Mary Jane sandal, cast adrift at the bottom of an empty wardrobe.

The story of “The Red Shoe” began like this: Amelie and I were eleven years old. We had a habit of stealing from department stores on Thursday afternoons. We did this for one year. They soon forgot about stealing stuff from the stores when they became fixated instead on the mystery policeman hired by her friend’s mother to scare them into law-abiding innocence. They replaced desire with desire—another kleptomaniac fantasy that took place on the streets of Paris.

Twenty years later and I am retracing Calle’s and Freud’s steps. It is a dark grey Monday morning. Sudden convulsions of wind, spitting drizzle like the cough of a hysteric, are unsteadying my strides as I make my way across London to the leafy, private-gated streets of Hampstead. I feel like an intruder, an interloper, intercepting and pilfering archival texts. I turn the pages of a handmade book bound with red ribbon, within which are stuck glossy photographs documenting the installation, tinted orange, the colour of a seedy bedroom light. This feels like an intimate album of private images, not meant for the press. Some photographs are missing but the holding pencil marks are still visible:

wedding dress

and then

phallic objects

The pictures have been stolen, an absence in which I cannot help but fall. From frayed graphite words to kleptomaniac desire, and new stories: of a woman ransacking a famous psychoanalyst’s collection of strange phallic objects while adorned in her bloody wedding dress. The police tried to catch her but she escaped their every move.

Postscript

Calle turns her appointment with Freud into a feminist act of fraying kleptomania. Inspired by Calle, Kivland, Cixous and more, I want to fray and fantasize the case histories of past and present kleptomaniacs, by giving them a voice which rips through silence.

She is right there; I can hear her mess.

Alice Butler will be running a series of reading & writing workshops on Kleptomania, Art and Feminism at the Freud Museum this summer. Details >>

Works stolen and cited

Ahmed, Sara. Living a Feminist Life. Durham, NC, and London: Duke University Press, 2017.

Berlant, Lauren. “On the Case.” Critical Inquiry 33:4 (summer 2007): 663-672.

Bernheimer, Charles and Claire Kahane, eds. In Dora’s Case: Freud-Hysteria-Feminism. New York: Columbia University Press, 1990.

Calle, Sophie. Appointment. London: Thames & Hudson / Violette Editions, 2005.

Camhi, Leslie. “Stealing Femininity: Department Store Kleptomania as Sexual Disorder.” differences: A Journal of Feminist Critical Studies 5:1 (1993): 26-50.

Cixous, Hélène, and Sarah Burd. “Portrait of Dora.” Diacritics 13:1 (Spring 1983): 2-32.

Freud, Sigmund. A Case of Hysteria (Dora). Translated by Anthea Bell. Introduction and Notes by Ritchie Robertson. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013.

Herbert, Susannah. “Will the real Sophie Calle please stand up?” The Telegraph, 8 February 1999.

Kivland, Sharon. A Case of Hysteria. London: Book Works, 1999.

Stewart, Susan. On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection. Durham, NC, and London: Duke University Press, 1993.