Gesticulations

In the short story “Complicity,” the American writer Dodie Bellamy describes the kleptomaniac activities of a friend named Lizzie: collects her favourite methods and her pilfered materials.

We’re not in nineteenth-century Paris, but it feels like we could be. The contagion of klepto-compulsion has spread to 1990s Sonoma County, California. As Bellamy writes:

Lizzie feels an extraordinary calm at the moment of theft. Outside a jeweler’s window, she doesn’t think she will steal. No sooner does she get inside than she’s sure she’ll come out with a jewel: a ring or handcuffs. This certainty is expressed by a long shudder which leaves her motionless.

Lizzie’s desire manifests in her body—a quivering vibration. Even her favoured goods—in the form of a ring (for her wedding finger?) or handcuffs—recall the determined hands of the kleptomaniac, which do the desiring taking. Lizzie enacts revenge on the circular locks that have contained women and hysterics, by stealing them back, in perverse circumscription of the law.

The kleptomaniacs’ hands rub, stroke, grope, pluck and slash: gesticulations of perverse desire.

Sheer detail

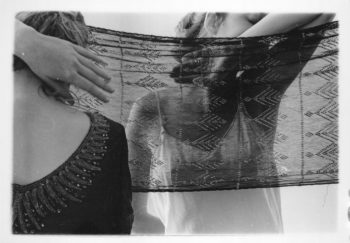

Francesca Woodman, Untitled, New York, 1979-80. Gelatin silver estate print 20.3 x 25.4 cm 8 x 10 in © Charles Woodman / Estate of Francesca Woodman / Artists Rights Society and Victoria Miro, London/Venice

In Francesca Woodman’s black-and-white photographs, the artist’s long exposures illuminate slender hands rubbing naked knees; airborne arms with climaxing wrists dressed in wood; bare fingers pushing bare walls; a squeeze of the flesh; a gasp at the mouth, all enacted by her celluloid paws. Aroused by these bodily details, I am spellbound by her paws.

And so while Naomi Schor writes in Reading in Detail that the detail is gendered and doubly gendered as feminine, I’m interested in what happens when the feminine detail explodes, becomes something more than ornament: displaces it. This is a perverse way of looking that echoes Roland Barthes’s discovery in Camera Lucida that inanimate objects when photographed can animate the imagination. He calls this the punctum of the photograph—a partial object—that pricks, bruises, and wounds the viewer, in unpredictable ways. However lightening-like it may be, writes Barthes, the punctum has… a power of expansion. This power is often metonymic. So often it is clothes or jewellery that wounds the effeminate Barthes in Camera Lucida, reminding him of lost relatives, former lives.

And it is the gold-flecked, antique-lace shawl that two young girls pluck like a harp, which pricks me (I’m a masochist) in a Francesca Woodman photograph. It has metonymic power, becoming a kleptomaniac detail the closer I look, then write. The photographic, tactile detail touches me into writing, as I move between vision, feeling and words.

“A woman’s fetish tendency is not simply a manifestation of a tame, essential femininity but, rather… the semiosis of a subversively erotic practice, thoroughly ‘perverse’ in its own terms.”Their silk-slipped bodies face one another, erotically close and apart. It’s only the grainy texture of the fraying fabric that divides them, as they enfold its folds, bringing it closer to their skin in haptic contact, a mode of clothing fetishism, close to the ways Emily Apter describes it. Going against the early psychoanalytic belief that perverse practices such as fetishism, sadomasochism, exhibitionism, and voyeurism required a male agent in the early chronicles of deviant practice, Apter shows—by discussing the artist Mary Kelly’s object cathexis: her collecting of domestic artifacts stamped with the coprophilic odors of the real: flowers, clothing, keepsakes, baby relics—that a woman’s fetish tendency is not simply a manifestation of a tame, essential femininity but, rather… the semiosis of a subversively erotic practice, thoroughly ‘perverse’ in its own terms.

Woodman delicately handles this subversion in her monochrome mirror image of two young girls grazing lace in dreamy, autoerotic arousal. While Gatian Gaetan de Clérambault suggested in his 1910 case studies that women’s contact with silk was asexual and passive; I’m reading this textured detail differently. I’m touching their touching perversion, in words and photographs, as I finger the leaves of Carol Mavor’s book to my left, rubbing its inked words: Woodman… is a clothing fetishist who weaves her perversion with photography.

Could this be the active, desiring masturbating girl that Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick describes: with her eyes-closed, stroking sheer things?

Sheer jouissance in more ways than one.

I’m gesturing; echoing the girls’ haptic gestures. Like Renu Bora in his essay on Henry James, “Outing Texture,” I’m unravelling queer threads, pulling at the ways in which shifts in texture (in Woodman’s photograph: the bold introduction of embroidered sheer lace) open up different spatial and bodily erotics.

Reading with the metonym of kleptomania helps me to touch the complexity of desire, of private acts deemed perverse, of two young women, friends or lovers, touching through fabric. In the essay “Jane Austen and the Masturbating Girl,” Sedgwick also turns to the nineteenth century in Austen’s 1811 novel Sense and Sensibility. (Remember it was Jane Austen’s aunt who was once caught stealing lace.) The novel’s erotic axis, Sedgwick writes, is most obviously the unwavering but difficult love of a woman, Elinor Dashwood, for a woman, Marianne Dashwood, which Sedgwick argues, can only be understood as not simply same-sex-loving or cross-sex-loving, unless we consider Elinor’s own queer identity as a masturbating girl. The 1881 manuscript of the novel is revealing in so many ways: One night she succeeds in rubbing herself till the blood comes on the straps that bind her.

Kleptomaniac touch

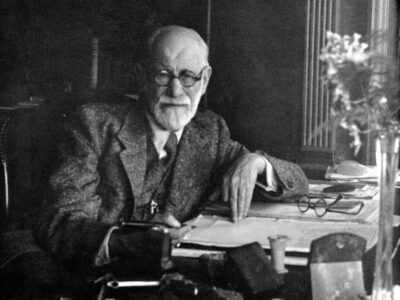

Rugs and cushions on Freud’s couch.

Could this be a perverse understanding of the ‘feminine touch’? This old adage immediately links women to the tactile sense, the base body not the elevated mind, conjuring associations of handiwork, and housework, the glory days of multitasking. Despite being an avid, haptic collector of oriental rugs and cushions, which comforted his patients throughout their own verbal weaving that was the talking cure, Freud’s 1933 essay “Femininity” reinforced this gender prejudice with the suggestion that women’s greatest cultural achievement is plaiting and weaving. Discovering their lack of a penis, Freud argued, brought shame and anxiety, and so in a desire to imitate the pubic hair that conceals the genitals, women learnt to weave, knit and embroider in feminized touch.

The kleptomaniac offers a different way into thinking through the connections between fabric, flesh and desire: one that is more closely tied to the haptic, given its etymological roots in the Greek verb haptein, which means to take hold of an object, fasten, or touch. Or as Bellamy describes it in “Complicity,” this time in reference to sex not shoplifting: Not buying, not receiving. Taking. To take hold implies bodily agency, possession, an ownership of sexual desire, its crossed threads—a way of feeling and negotiating spaces and objects, while gesturing towards something that might not yet be known.

Indeed Laura Marks has theorised haptic visuality as a mode of knowing in which the eyes themselves function like organs of touch, enabling a mode of looking through texture. This emphasis on the haptic as a way to look and touch simultaneously opens up the possibility that vision is also an act of taking, or taking back, corporeal agency and sexual desire, a way of being in space. It’s perhaps for this reason that Rizvana Bradley has claimed haptic experience as minoritarian experience.

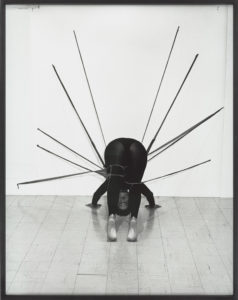

Senga Nengudi, Performance Piece, 1978. Courtesy of the artist; Lévy Gorvy, New York and London; Thomas Erben Gallery, New York. © Tom Powel.

Bradley has also picked up on the haptic qualities laced throughout African-American artist Senga Nengudi’s series of performance-based sculpture called R.S.V.P. Much like a headless Francesca Woodman in the 1975-78 photograph Verticale, Nengudi also takes pleasure in stockings: the quivering hands and legs that graze them, inside and out. Playing with the idea that a woman’s life is in her purse, Nengudi is a thrifty kleptomaniac: stealing black, tan and nude stockings for her own ends, filling them first with sand, and then stretching and contorting their forms into a spider’s web of extra limbs and detached body parts, inviting further activation from the spandex-clad bodies that dance and entangle themselves through it.

The artist’s mesh prosthetic forms recall the fragmented bodies that fill the department stores in Émile Zola’s nineteenth century novel about kleptomania, The Ladies’ Paradise, but Nengudi’s approach is never passive-pathological. Instead, the artist actively mines space for the difficult, embodied aspects of black life, history and culture—the black female body historically being a victim of violence, of bodily disassembly—which Nengudi achieves through embodied gestures grabbing and manipulating typically feminine garments.

Echoing Peggy Phelan’s insights, I hereby wonder if one of the most revolutionary legacies of feminist art concerns the epistemological contours of touch itself, but more than that—a kleptomaniac touch that is haptic, possessive, and perverse.

And so I turn back to Francesca Woodman—I try to read what what’s written on the cutting of paper that sits like a feather on her open palm. The photograph is from 1976; its title is: And I had forgotten how to read music.

But forgetting can mean begetting. Her kleptomania secret is out.

Works cited (or stolen)

Apter, Emily. Feminizing the Fetish: Psychoanalysis and Narrative in Turn-of-the-Century France. Ithaca, NY, and London: Cornell University Press.

Barthes, Roland. Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography, translated by Richard Howard. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1981.

Dodie Bellamy, “Complicity.” In Pink Steam, 24-36. San Francisco: Suspect Thoughts Press, 2004.

Bora, Renu. “Outing Texture.” In Novel Gazing: Queer Readings in Fiction, edited by Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick. Durham, NC, and London: Duke University Press, 1997.

Bradley, Rizvana. “Introduction: other sensualities.” Women & Performance: a journal of feminist theory 24:2-3 (2014): 129-133.

———. “Transferred Flesh: Reflections on Senga Nengudi’s R.S.V.P.” TDR: The Drama Review 59:1 (Spring 2015): 161-166.

Freud, Sigmund. “Femininity.” In The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud Volume XXII (1932-1936): New Introductory Lectures on Psycho-Analysis and Other Works, translated and edited by James Strachey, 112-135. London: Vintage, 2001.

Kosofksy Sedgwick, Eve. “Jane Austen and the Masturbating Girl.” Critical Inquiry 17 (Summer 1991): 818-837.

Marks, Laura. The Skin of the Film: Intercultural Cinema, Embodiment and the Senses. Durham, NC, and London: Duke University Press, 2000.

Mavor, Carol. Becoming: The Photographs of Clementina, Viscountess Hawarden. Durham, NC, and London: Duke University Press, 1999.

Phelan, Peggy. “The Returns of Touch: Feminist Performances, 1960-1980.” In WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2007.

Schor, Naomi. Reading in Detail: Aesthetics and the Feminine. New York: Methuen Inc., 1987.

Sherlock, Amy. “Senga Nengudi.” frieze 169 (March 2015). Accessed here, Date accessed: 22 February 2019.