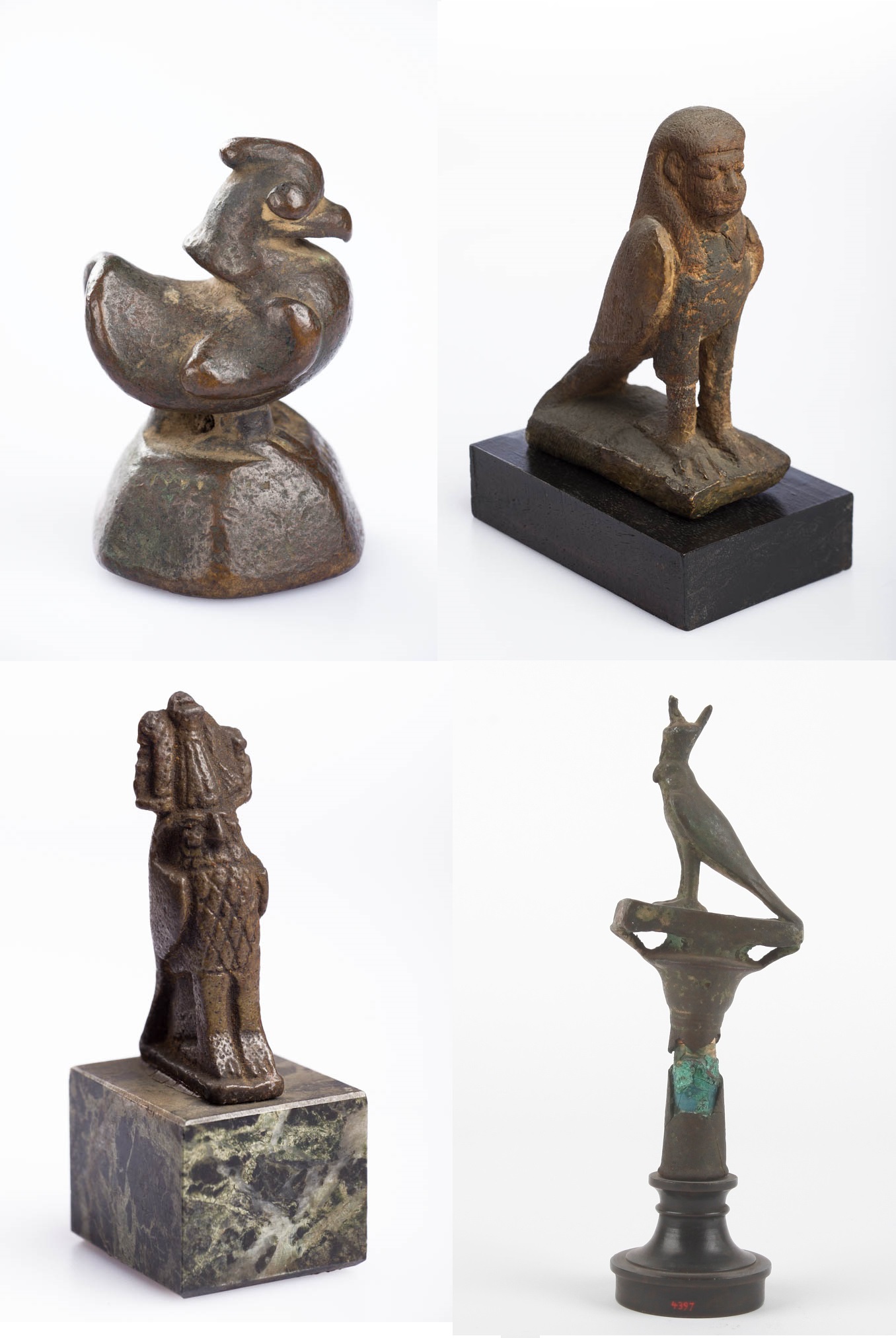

Animals appear often in Freud’s collection of antiquities. From horses to baboons, snakes to porcupines, Freud’s study can sometimes appear as a bronze and terracotta jungle. But look closely and you’ll see that one type of animal appears more than any other: birds.

Birds are particularly well represented in the Egyptian collection. In Egyptian mythology many deities took the form of animals, or animal-human hybrids.

Falcon-headed figure, Egyptian

The falcon-headed figure above is a representation of the god Horus, son of Isis, who avenged the murder of his father Osiris, king of the underworld. Freud probably bought this as part of a group of figures bought from the Viennese antiques dealer Robert Lustig in 1931.

Falcon-headed figures appear in an anxiety dream Freud had in childhood, which he analyzed thirty years later in The Interpretation of Dreams:

“In it I saw my beloved mother, with a peculiarly peaceful expression on her features, being carried into the room by two (or three) people with birds’ beaks and laid upon the bed. I awoke in tears and screaming and interrupted my parents’ sleep. The strangely draped and unnaturally tall figures with birds’ beaks were derived from the illustrations to Philippson’s Bible. I fancy they must have been gods with falcons’ heads from an ancient Egyptian funerary relief.”

Left: Human headed Ba-bird, Egyptian, Ptolemaic Period 323BC – 30BC. Right: Amulet of the goddess as a vulture, Egyptian, Late Period 716BC – 332BC

Freud’s collection features many figures of Ba-birds. Ba-birds, like the one above, were often found atop Ptolemaic funerary stelae, representing the ba (individuality) of the deceased. Other aspects represented the body itself and the ka, or life-force. Unlike the body, the ba was not a prisoner of the tomb. It was represented in the form of a bird as it could take flight in order to visit the land of the living and enjoy the pleasures that it left behind.

The Egyptians identified the vulture with a number of deities, including Nekhbet of Elkab, the main protector of Upper Egypt. The small bronze piece above is probably intended to represent Nekhbet.

In hieroglyphic script, the vulture stands as the sign for mut (mother), after another vulture goddess, Mut, one of the maternal guardians of the Pharaoh. Unlike Nekhbet, Mut is more often represented in human form. An examination of the Egyptian vulture deity became central to Freud’s argument in his essay Leonardo da Vinci and a Memory of his Childhood.

This falcon reliquary above is of Haroeirs, perched on a hollow rectangular container. The reliquary is in fact a still-sealed coffin for a sacrificed animal.

Certain animals were held sacred to ancient Egyptians because of their association with particular deities. The falcon represents Horus, the sky god, and with the double crown of a united Egypt. In later dynasties, animal cults, such as the one dedicated to falcons, became increasingly popular and even had their own priesthoods. Pilgrims could purchase the ritually sacrificed and mummified remains of an animal, placed within a coffin, as offerings to a god. These could be falcons, fish, crocodiles, shrews, or many other types of animals.

This coffin in Freud’s collection probably came from one of the sites where falcon worship was common, such as Giza and Buto. Although this seems like an elaborate way to offer a sacrifice, these reliquaries were often made extremely rapidly, in a production-line style.

Top left: Statuette of chicken, East Asian, date unknown. Top right: Human headed Ba bird, Egyptian, Late Period 747BC -332BC. Bottom left: Falcon wearing atef-crown, Egyptian, Late Period 747BC -332BC. Bottom right: Terminal in the form of a papyrus sceptre with a falcon, Egyptian, Late Period 747BC -332BC