When Anna Freud died in 1982, she left instructions in her will for her home at 20 Maresfield Gardens to become a museum dedicated to the life and work of her father, Sigmund Freud. Over time that aim has expanded to include Anna Freud’s own life and contributions, as well as those of other analysts. The house in Hampstead, once a family home, is now a centre for learning, research and the arts.

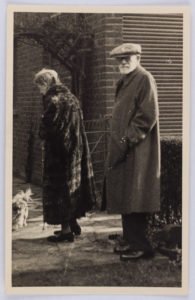

Martha and Sigmund Freud at 20 Maresfield Gardens, 1939

In September 1938, Sigmund Freud, his wife Martha, daughter Anna, and their housekeeper, Paula Fichtl, prepared to move into their new permanent home in the leafy north London neighbourhood of Hampstead. A little removed from the bustle of the city, Hampstead was already a refuge for many fleeing Nazi-occupied Europe. The area was inhabited by fellow psychoanalysts, as well as writers and musicians.

Freud, however, was not looking for social interaction. Already gravely ill, he would live in the house at 20 Maresfield Gardens for only a year before his death in September 1939.

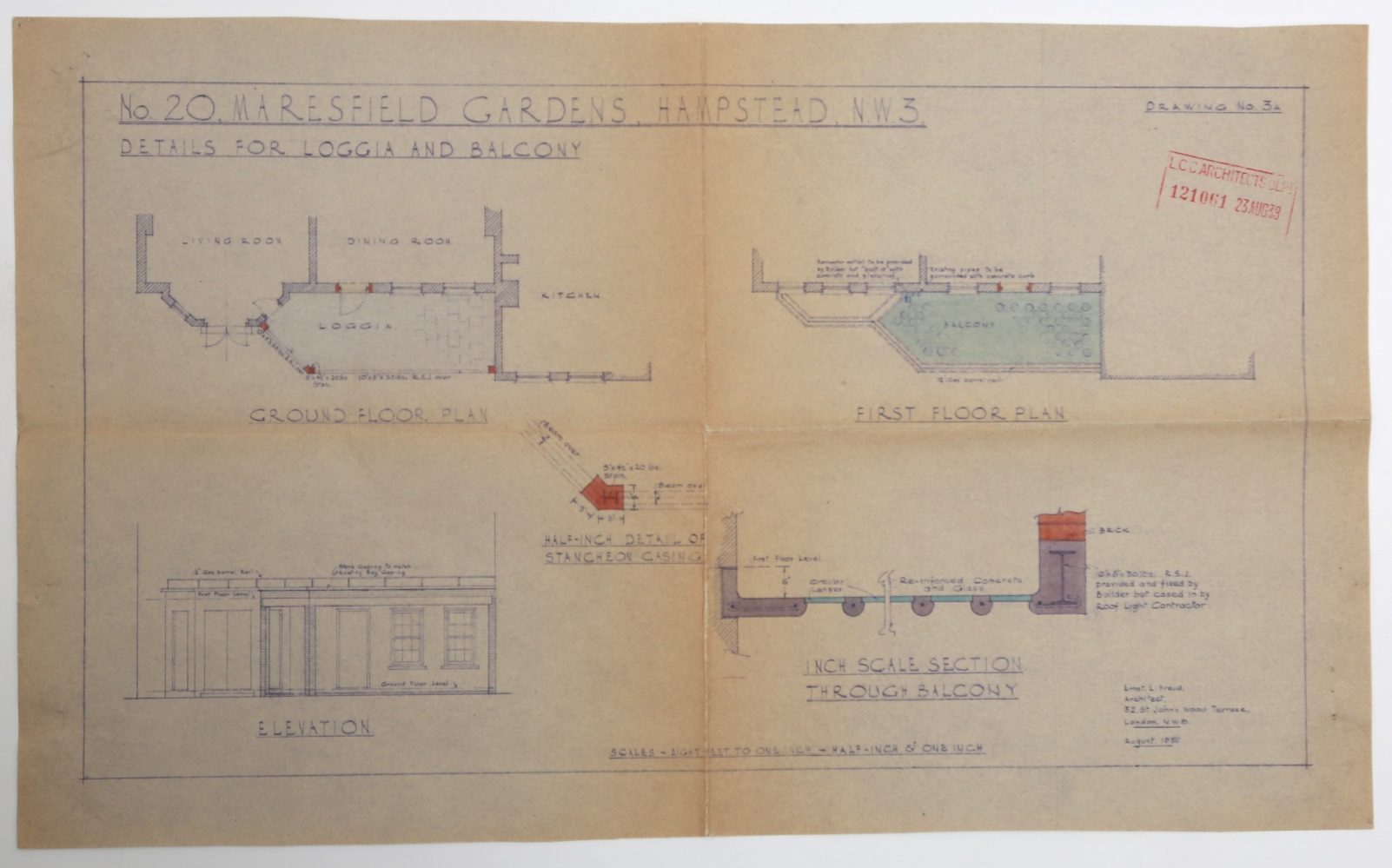

Before the family moved in there was work to be done. Freud’s son Ernst, a successful architect already living and working in London, made plans to improve the house and his father’s comfort. The wall between his father’s study and library was knocked down to create a bright, open work space that more closely resembled Freud’s consulting rooms in Vienna. A lift was installed, and in the large back garden a loggia was designed to allow the family to sit outside under shelter.

Ernst Freud’s original plans for the loggia, 1938

Freud said the house was too good for someone who would not tenant it for long, but that it was really beautiful

After Freud’s death, Anna Freud continued to live at Maresfield Gardens with her mother, her aunt Minna, and Paula. Freud’s study remained largely untouched, though was used by the family daily as a communal space. His antiquities, books and artworks stayed on their shelves, with Anna taking a few things from her father’s study to place in her own.

Anna’s work continued and she used the top floor of the house as her consulting room and study. As the years passed, the room next to this became a waiting room for patients and another became her secretary’s office.

Anna Freud’s consulting room, c. 1982

After Martha Freud’s death in November 1951, Anna’s lifelong friend and colleague Dorothy Burlingham moved into the house at 20 Maresfield Gardens. Anna and Dorothy lived, worked and wrote together in the house for decades to come.

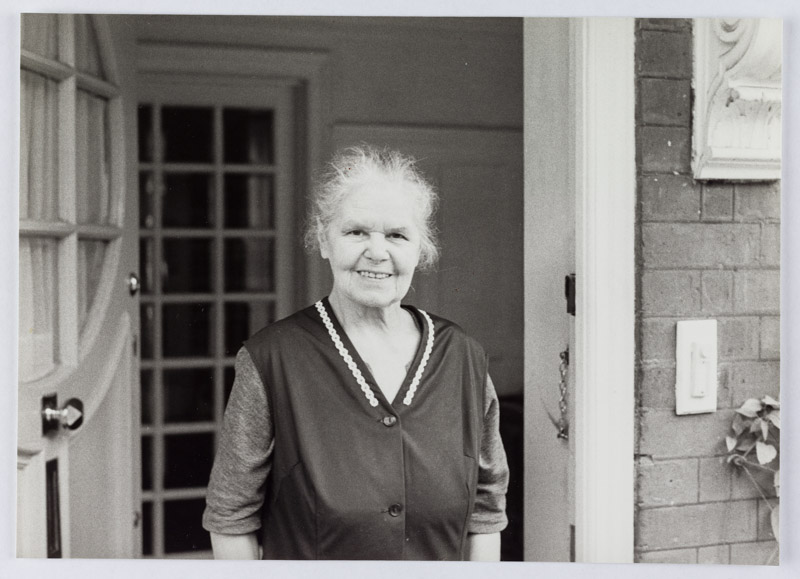

Anna Freud and Dorothy Burlingham at 20 Maresfield Gardens, December 1975

Dorothy Burlingham’s former bedroom is now where the museum’s Anna Freud Room is located. It had once been Martha Freud’s own sitting room. Next door, in what is now the museum’s Video Room, was Dorothy’s consulting room and study. This room was once Minna Bernays’s bedroom. Minna, Martha’s sister, had lived with the family in Berggasse 19, Vienna, and also came to London to escape Nazi persecution. She lived in the house until her death in 1941.

In 1951 Anna Freud, Dorothy Burlingham and colleague Helen Ross founded a new centre for child psychoanalysis, called the Hampstead Child Therapy Course and Clinic, just a few doors away at 12 Maresfield Gardens. Both Anna and Dorothy continued to work in the house at 20 Maresfield Gardens, surrounded by their own library and collections.

Two pictures of the kitchen, c. 1982

Despite being an energetic work space, the house was still a home. Paula Fichtl, who had been with the Freud family for decades, still oversaw the daily running of the house while Anna and Dorothy worked, travelled and published. The domestic spaces, the kitchen and dining room, reveal a rarely seen side of the Freud family life.

The dining room, c. 1980

The dining room – still referred to as such in the museum today – was a cosy room where the family ate and entertained, and in much later years housed the caretaker’s television set. Much of Anna Freud’s collection of traditional Jugendstil furniture was, and still is, in this room. The Jugendstil style emerged during the mid-1890s in Germany and Austria. Its decorative, often floral style was generally sentimental and naturalistic, drawing on natural forms and folk art themes. Anna’s collection of wardrobes and linen chests, as seen in the above image, came to London from her holiday home in Hochrotherd, a rural idyll outside Vienna.

Anna Freud’s bedroom c. 1982

Some parts of today’s Freud Museum, such as the dining room, are recognisable from their time as a domestic space. Others, such as bedrooms and bathrooms, are lost to history. Anna Freud’s bedroom (above) is now the museum’s meeting room, hosting groups, talks and events, and available to hire. Anna Freud’s living and working space is recreated in the museum’s Anna Freud Room.

The “blue bathroom”, c.1982

Some spaces, like the bathrooms, have been completely converted. The “blue bathroom” which was Freud’s bathroom, then Dorothy Burlingham’s, was torn out during the museum’s early renovation phase, around 1984. It is now the museum Director’s office.

Other areas remain private spaces. The caretaker’s flat on the ground floor once housed the family’s kitchen and scullery, as well as housekeeper Paula’s private room. A caretaker has occupied this space ever since.

A busy museum also needs office space. The top floor of the house now holds several offices, as well as a staff kitchen, bathroom, and archive and collection stores. Anna Freud’s former consulting room continues its role as a work space, housing offices for staff and researchers.

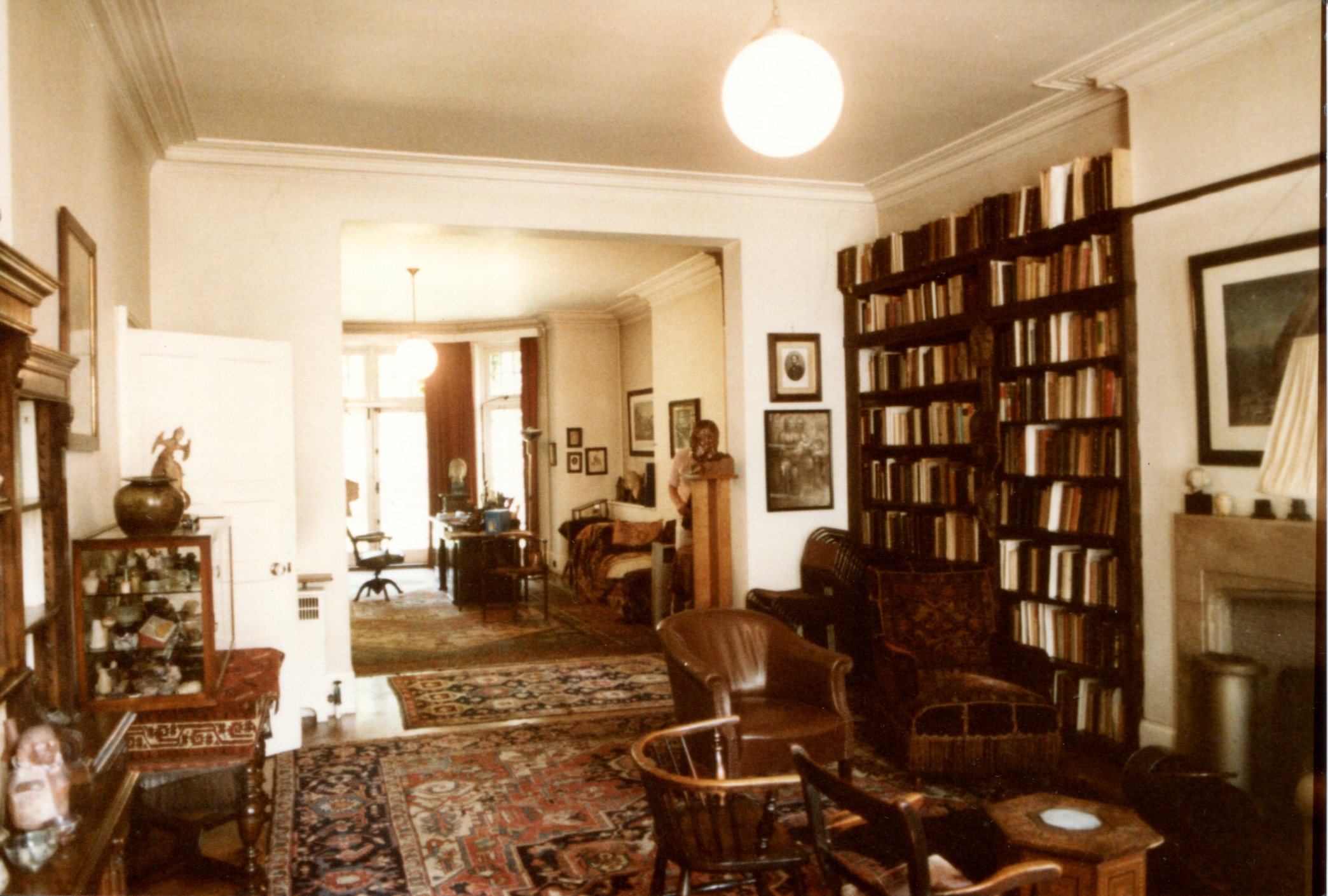

Sigmund Freud’s study c. 1982

One room, of course, remains a constant. Sigmund Freud’s study, filled with his books and antiquities, was arranged this way by his family in 1938. Since then very little has changed. Anna kept her father’s collection in place – not as a shrine never to be touched, but as a memory in which to live. The museum has striven to preserve this, keeping the furniture and objects as similarly placed as possible. Concessions to museum standards have been made, such as barriers and low-level lights, but the atmosphere remains.

The museum spaces blend the domestic and the public spheres. Opening up Sigmund Freud’s home was Anna Freud’s ultimate wish and today the museum continues to fulfil this goal. The collection, archive and photo library evoke the past, while the vibrant exhibitions and events programmes celebrate the present and continue to provoke conversations about art, psychoanalysis, mental health, society and culture for the future.

Sigmund and Anna Freud in the garden of 20 Maresfield Gardens. 1938

Freud’s desk in his study, c. 1970

Anna Freud and Dorothy Burlingham in the library at 20 Maresfield Gardens, c. 1976. Courtesy Michael J. Burlingham

Paula Fichtl in the doorway of 20 Maresfield Gardens, c. 1978

The back garden and loggia, 1980

The loggia, designed by Ernst Freud in 1938

20 Maresfield Gardens, 1979

Comments

Hi!

I have visited the house quite a few times (I live in Australia) .. it is a wonderful place to usually start any stay in London… we were having a debate as to how Freud came upon the house as he initially lived elsewhere in London… my question is did he own the house or was he assisted in this accommodation either by local Hamsteadites or by the British Government… we were having a discussion tonight and I confessed that I didnt know…

Would be interested if you can answer this question

Very Best and thankyou for this marvelous museum

Very Best

Andrew

Caulfield Melbourne

Hi Andrew

Thanks for your comment! Yes, when Freud first arrived in London he lived at a different property, 39 Elsworthy Road, NW3. This was rented and was just until the family found a permanent home. They bought this house at 20 Maresfield Gardens a few months later, with a down payment and a mortgage from the bank. Freud’s son, Ernst Freud, was an architect who had settled in London in 1933 and he provided help in finding this house and also making some renovations to make Freud comfortable.

I hope this answers your question.