One of the many bizarre claims of psychoanalysis is the importance of sexuality in the inner world.

Students visiting the Freud Museum often tell us that Freud must’ve had a one-track mind.

But there is an important nuance to be made: Freud connected sexuality not just to pleasure, but also to themes of loss, and above all anxiety.

Who invented sexuality?

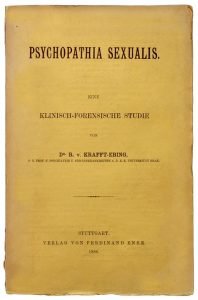

Psychopathia Sexualis by Richard von Krafft-Ebing. Image credit: Wikimedia Commons

A lot of people think Freud invented the modern notion of sexuality, but actually that dubious honour goes to the sexologist Richard von Krafft-Ebing.

In his 1886 book Psychopathia Sexualis, Krafft-Ebing presented a veritable catalogue of meticulously documented sexual practices. Sadly it’s not illustrated, although his rather racy postcard collection now resides in the archives of the Wellcome Collection.

The Psychopathia introduced terms that are very much in use today, such as ‘sadism’ and ‘masochism’, not to mention the now rather antiquated ‘heterosexual’ and ‘homosexual’.

The book could almost be read as a glowing tribute to human sexual diversity, but instead Krafft-Ebing cast it in the strict moral framework that dominated 19th Century approaches to sexuality. It was seen as a natural instinct for genital, heterosexual intercourse in the service of reproduction, absent in childhood and emerging only at puberty.

There was a normal way of doing it, and anything outside of that norm bore the mark of degeneracy. As the title made clear, deviations from the norm were to be understood as reflecting defects in one’s psychological makeup.

This was the picture of sexuality that Freud destroyed. But paradoxically, it was also his starting point.

Freud and the ‘sexual aberrations’

Freud called the first of his Three Essays on Sexuality ‘The Sexual Aberrations’.

The title is provocative: ‘aberration’ has biblical connotations, perhaps invoked by Freud to poke fun at Krafft-Ebing.

The standard critique of norm-deviation models like Kraft-Ebing’s is that the norms they uphold are relative to prevailing cultural values, but Freud’s critique takes us a step further.

In his essay, Freud makes an interesting observation: you can find toned-down versions of many of the so-called perversions in just about everyone. They are refracted in myriad ways in the kinks of everyday life: in touching, looking, kissing, and so on.

Not only this, but they are often at loggerheads with internal counter-forces such as shame and disgust, and the line between them isn’t at all clear-cut. “A man who will kiss a girl’s lips passionately,” Freud wrote, “may perhaps be disgusted at the idea of using her toothbrush.”

The standard critique of norm-deviation models like Kraft-Ebing’s is that the norms they uphold are relative to prevailing cultural values, but Freud’s critique takes us a step further. He was also interested in how these models tend to involve a degree of splitting and projection.

The logic of norm-deviation models is: ‘I am normal; they are perverse’. For many of us encountering Freud for the first time, it is: ‘I am normal, Freud is perverse’. But in Freud’s view, this split is located not between between self and other, but is internal to each subject: when it comes to sexuality, we are all internally divided.

Polymorphous perverse

“It is an easy conclusion that ‘normal’ sexuality has emerged out of something that was in existence before it.”Sigmund Freud

Freud argued that sexuality needs to be redefined. His basic claim is that it is not a unified instinct for reproduction, but rather is a kind of mosaic.

Just as Isaac Newton had shown that white light is in fact a composite made up of different coloured rays, Freud showed that sexuality is a composite of different drives of the body pushing for satisfaction. “It is an easy conclusion,” he wrote, “that ‘normal’ sexuality has emerged out of something that was in existence before it.”

Going far beyond the superficial norm of hetero-genital reproduction, the picture of sexuality that emerges with Freud is one that begins long before we were ‘sexually active’ in the adult sense: before that first kiss, before that well-known teenage pastime, before the temper tantrums, even before the heydays of potty training and thumb-sucking. Freud traced it all the way back to the ‘polymorphous perverse’ days and nights of earliest infancy.

A baby’s first experience of satisfaction, he observed, is at its mother’s breast. In psychoanalytic jargon, this makes the breast the first ‘object’, setting the child up for the crisis of its inevitable loss, the mouth becoming the site of this unmitigated tragedy.

Freud and the ‘psychosexual stages’

Freud has become known as that guy who gave us the ‘psychosexual stages of development’, but it isn’t really central to his argument.

Freud has become known as that guy who gave us the ‘psychosexual stages of development’, that sequence of preoccupations and losses (of the ‘oral object’, the ‘anal object’ and so on) that lay the foundation for our adult lives. But strangely enough, it isn’t really central to his argument.

In fact, the real impetus for the idea came from one of his students, the psychoanalyst Karl Abraham. Before becoming a psychoanalyst, Abraham had trained as an embryologist, and a glance at his pre-analytic research reveals his penchant for neat developmental charts of stages and sub-stages, which he carried over into his work as a psychoanalyst.

It was Abraham who theorised a natural progression from one stage to the next: oral, anal, phallic and genital (other drives identified by Freud having slipped the net).

Freud recognised that the polymorphous sexuality of children must undergo a complex process of regulation during development, and that at certain points in infancy one drive or another may have the upper hand. He thought it likely, for instance, that an ‘oral stage’ must precede an ‘anal stage’ since weaning precedes potty training, but he was cautious about introducing the kind of timelines that we find in today’s textbooks.

His endorsements of the theory of psychosexual stages are few and far between, and are almost always framed as speculations or accompanied by warnings. They are “nothing but constructions,” he urged, and “it would be a mistake to suppose that these phases succeed one another in a clear-cut fashion.”

Freud argued that time is out-of-joint in human experience. There is, he wrote, a “discontinuous method of functioning” beneath our clumsy understandings of time as passing smoothly from one moment to the next. As scholar Joan Copjec puts it, the mind is precisely “de-phased” in Freud’s work.

How did the theory of psychosexual stages rise to prominence?

I have always been perplexed as to why the ‘psychosexual stages’ have become elevated to a cornerstone of psychoanalysis. Repeatedly attributed to Freud, they were really just a by-product of Abraham’s ideas about – ironically enough – parrots.

Through the theory of the stages, the analysts of the 1950s could offer the US a roadmap to prevailing cultural values of autonomy and enterprise.

A likely explanation is that this view rose to prominence as part and parcel of a move by émigré psychoanalysts in the post-war United States to establish psychoanalysis as a respectable academic psychology.

Through the theory of the stages, the analysts of the 1950s could offer the US a roadmap to prevailing cultural values of autonomy and enterprise: an emotional re-education involving the overcoming of ‘fixations’ in order to arrive at a so-called ‘genital personality’.

You don’t have to read much Freud to realise he would have thought this was baloney. He didn’t think the unconscious was neatly stratified into layers. He wasn’t convinced that the American Dream of ‘genitality’ was achievable. And above all, he didn’t think psychoanalysis should, or even could, be used to adapt people to cultural norms. Such endeavours (rife in today’s therapeutic landscape) bring us back to norm-deviation models: they are on the side of the tyrannical superego, which polices our conformity to norms and ideals.

Freud didn’t think psychosexual stages are hard-wired into our psychological make-up.

So how can we find something valuable in this endlessly repeated theory?

If any such itinerary exists, it is on the side of the other, the caregiver, who bring the stages into focus through his or her interactions with the infant.

One thing we might do is to highlight the dimension of the ‘other’. In early works, Freud referred to the “prehistoric, unforgettable other person who is never equalled by any one later.” If any psychosexual itinerary exists, it is on the side of the other, the caregiver, who bring the stages into focus through his or her interactions with the infant. Through the impositions, the demands, and even the very rhythm of his or her comings and goings, the caregiver leaves an indelible mark on the child.

We could even say that without weaning there would be no ‘oral stage’, without potty training no ‘anal stage’. A truly Freudian theory of sexuality thus has to factor in the impact of the ‘other’.

Crucially, Freud saw this not only as an other of need, but also of speech. In his early work, he observed that the caregiver not only attends to the baby’s bodily needs, but also names the baby’s cries, absorbing its various bodily impulses, disturbances, satisfactions and drives into language, and laying down the all-important dos and don’ts that frame those decisive early triumphs and losses. In the process, sensations in the body get tangled up with traces of speech which, Freud theorised, leave imprints in the unconscious.

Thus, in a certain sense, as the psychoanalyst Bruce Fink has observed, a slip of the tongue is in fact a slip of the other’s tongue: the desires and ideals of our caregivers speaking, unconsciously, through us.

In his later work, Freud returned to this theme of language, describing the unconscious as a system of ‘representatives’ of that mosaic of bodily drives pushing for satisfaction. Where do those representatives come from? From the speech of our caregivers.

From stages to staves

What if, rather than seeing the psychosexual stages as a developmental sequence, we instead follow Freud in placing the accent on speech and language?

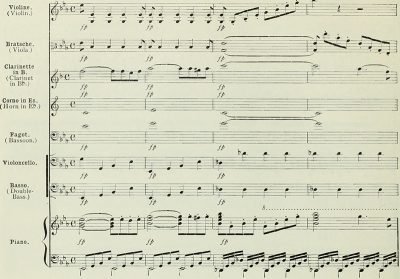

An orchestral score. Image credit: Wikimedia Commons

Here I find it helpful to think of speech as a kind of orchestral score. It unfolds over time from left to right, but you can also read it from top to bottom, with each instrument occupying a line.

The violins might be playing an upbeat melody, but why that ominous, barely audible murmur from the horns?

Similarly, human speech is constantly inhabited by inflections and double-meanings that, if examined, may tell a very different story to the intended one.

Not long ago, I was invited to give a talk at another institution, on the subject of pornography. After the talk, the organiser congratulated me with an accidental double entendre and immediately turned red: ‘I can’t believe how many people came!’ In another example, a pianist friend was learning a difficult piece that involved a sudden change of octave. ‘I really want to nail this passage,’ he lamented, ‘but I can never get my fingers down to the bottom.’ In describing a frustration in his professional life, he had found himself using an anal register.

Freud often suspected that it is precisely because of the proximity in which they place us to these hidden registers of sexuality that many of us find his ideas difficult to… swallow.

Instead of thinking of stages of development, we should instead think of them as staves of speech.

Perhaps then, instead of thinking of stages of development, we should instead think of them as staves of speech. The instruments that make up the score would be those drives of the body: oral, anal (clearly a wind instrument), scopic (looking and being looked at), invocatory (hearing and being heard), and so on.

“The technical language of psychoanalysis is ugly and crude,” analyst Susie Orbach recently commented, ‘but the words and ideas that emerge in sessions sing.” Anyone with ears to hear will sometimes catch a note, but in psychoanalysis the task is to bring out these unique compositions. To do so, one listens not from the position of the expert who wields some supposed knowledge of, say, the psychosexual stages, but rather from that of curiosity. Psychoanalysts allow themselves to be led by their patients, but they address their questions at the multiple staves of the score that makes up speech, intervening not at the level of the conscious, intended message, but at the level of those lost objects of prehistory that nestle in the ambiguity of what we’re saying: in the slips and stumblings that are characteristic of human speech.

Farts that don’t work

The psychoanalyst Adam Phillips quite literally struck gold when a boy of ten was referred to him having become ‘preoccupied and sad’. The boy’s mother said he had become unable to ‘work’ in school, and repeatedly emphasised that he had ‘worries’ that he kept to himself. In the first session, Phillips reports, he made a blunder that turned out to be quite productive:

“Intending to say ‘What are the worries?’ I in fact said to him ‘What are worries?’ Quite naturally puzzled by the question, he thought for a moment, then replied triumphantly, ‘Farts that don’t work,’ and blushed. I said, ‘Yes, some farts are worth keeping.’ He grinned and said, ‘Treasure.’ It transpired from our conversations that worries were like gifts he kept for his mother, and he was fearful of running out of them.”

Many contemporary therapies take a wrong turn by implicitly assuming that speech is a means of intentionally conveying information. In cognitive therapies, the boy’s ‘worries’ might be taken at face value, measured according to a predefined notion of ‘reality’ (that norm-deviation model again), the reality in which the worries are not farts that don’t work, but the result of faulty cognition to be corrected.

In a cognitive-behavioural therapy, a slip of the tongue might be regarded as meaningless. In psychoanalysis, it is a fragment of sacred text.

For psychoanalysis, meaning is never obvious. “Are there not very important things,” Freud reflected, “which can only reveal themselves by quite feeble indications?” In other words: the devil is in the detail. One should always listen out for those inconspicuous slips, stumblings and interruptions that the ego is trying to conceal.

In a cognitive-behavioural therapy, a slip of the tongue might be regarded as meaningless. In psychoanalysis, it is a fragment of sacred text. “We have treated as Holy Writ”, Freud remarked, “what previous writers have regarded as an arbitrary improvisation, hurriedly patched together in the embarrassment of the moment.”

A fuller kind of speech

By shifting the emphasis in psychosexuality from stages to staves (or, if you prefer, from phases to phrases), we can start to understand how and why psychoanalysts strive to introduce their patients to another, fuller kind of speech: one in which painful associations can emerge and evaporate, one that introduces them to something of how they construct their objects, and perhaps also one that can allow them to glimpse the void behind these objects, opening up the possibility of reconstructing them in a way that makes life more bearable.

A visit to the Freud Museum can help your students sort Freud-fact from Freud-fiction.